The New York Times: Wrestling over Charlie Kirk’s legacy and the divide in America

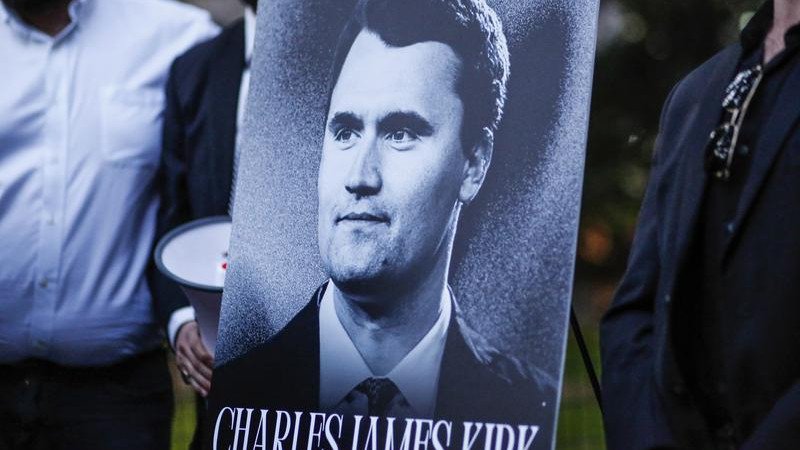

THE NEW YORK TIMES: The nation is at another polarised moment after the assassination of Charlie Kirk, the 31-year-old conservative activist gunned down on a college campus in Utah.

On the night in April 1968 that the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, Sen. Robert F. Kennedy, then a candidate for president, told a shocked and largely Black crowd in Indianapolis that “it is perhaps well to ask what kind of a nation we are and what direction we want to move in.”

“Those of you who are Black,” he said, could be filled with “a desire for revenge.” Or, he said, the nation could try to replace violence “with an effort to understand.” It was considered one of the finest speeches of his life. But in the wake of King’s death, riots, looting and arson erupted in more than 100 US cities, and Kennedy was assassinated that June in California.

Fifty-seven years later, the nation is at another polarised moment after the assassination of Charlie Kirk, the 31-year-old conservative activist gunned down on a college campus in Utah. Beyond an ability to inspire passion in others, King and Kirk had almost nothing in common. But their killings occurred in a country awash in violent political rhetoric and partisan anger.

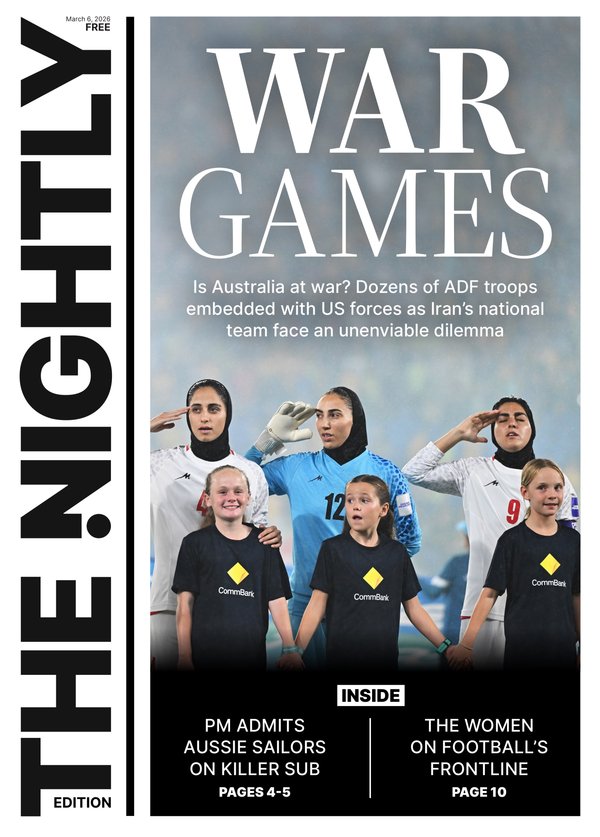

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Americans are now grappling with the brutal killing of a young leader who is viewed through radically different lenses. On the right, Kirk has been lionized as an inspiration to a new generation of Republicans. On the left, he has been pilloried as a divider who attacked civil rights, transgender rights, feminism and Islam.

As people wrestle over Kirk’s legacy, historians and scholars say the lessons of this particular time will depend on Americans themselves. It is another test, they say, of the American experiment.

“Does a reprehensible crime against a political figure lead to more reprehensible acts, or does it remind us that we have to be able to live with people whose opinions we despise without resorting to violence?” asked presidential biographer Jon Meacham. “If this is open season on everybody who expresses an opinion, then the American covenant is broken.”

In the immediate aftermath of Kirk’s killing, anger has pulsed loudly. President Donald Trump blamed the left for what he said was savage rhetoric that had led to Kirk’s death and vowed to go after “those who contributed to this atrocity.” Democrats and Republicans in Congress lashed out at one another and are ever more fearful for their safety. People who castigated Kirk and his views have been targeted and exposed by right-wing influencers. Mentions of the term “civil war” skyrocketed on social media platforms.

Gov. Spencer Cox of Utah, a Republican, has stood out for trying to turn down the heat. “This is certainly about the tragic death, assassination, political assassination, of Charlie Kirk,” he said at a news conference Friday. “But it is also much bigger than an attack on an individual. It is an attack on all of us.” Kirk, he said, championed free speech, and “in having his life taken in that very act makes it more difficult for people to feel like they can share their ideas, that they can speak freely.”

Kirk did speak freely. He called King “awful” and “not a good person.” He described the Civil Rights Act as a “huge mistake” and George Floyd as a “scumbag.” He said that Islam “is not compatible with Western civilization” and accused “Jewish donors” of fueling radicalism by financing “not just colleges — it’s the nonprofits; it’s the movies; it’s Hollywood; it’s all of it.” Democratic women, he said, “want to die alone without children.”

But among thousands of young conservatives on American college campuses, he was a rock star, a gifted speaker who relished debating with more liberal students. At the 2024 Republican convention, he reached out directly to his generation. “Democrats have given hundreds of billions of dollars to illegals and foreign nations, while Gen Z has to pinch pennies just so that they can never own a home, never marry and work until they die, childless,” he said.

To Brad Parscale, Trump’s first campaign manager in 2020, Kirk “loved America and was truly remarkable.” Parscale recalled that Kirk, the founder of Turning Point USA, the nation’s preeminent right-wing youth activist group, had come to him in 2018 to offer his help for the campaign. “But I told him, ‘Go do your own thing, and you’ll help the president 100 times more. The campaign will hold you back. You’re bigger than this.’ And he was,” Parscale said.

To Dan Carter, author of “The Politics of Rage: George Wallace, the Origins of the New Conservatism and the Transformation of American Politics,” Kirk was a dark force. His assassination, he said, “is a terrible thing for America, but I don’t think we gain anything by embracing him as some kind of open-minded individual who strengthened democracy.”

Bishop Mariann Edgar Budde of the Episcopal Diocese of Washington, who angered Trump when she asked him the day after his second inauguration to “have mercy” on immigrants and LGBTQ+ people, said rage from those anguished over Kirk’s death was to be expected.

“Public grief is necessary, and this is a time for those who loved and admired Charlie Kirk to grieve and to grieve publicly,” she said. “For those who were hurt or aggrieved by his positions, I think this is a time for us to be gracious and allow grief to be expressed — and at the same time, not to be surprised that other emotions are also communicated.”

When someone dies, she said, “we try to focus on the good, to the point that some people say, ‘I don’t recognise the man who is being eulogised.’ But I hear that from a son speaking about his father. I’ve been in those rooms. If that happens in family life, why would we be surprised if it happens in our national life with a public figure? Can’t we be gracious about that, too?”

Dannagal Goldthwaite Young, a professor of communications at the University of Delaware who researches media psychology and public opinion, said she had noticed a restraint in mainstream media reporting about Kirk’s death.

“I think there is a recognition that this moment is so important, and this country is such a tinderbox, that people who are in media and journalism, especially those on the left, are aware that they have a responsibility to take the temperature down. And I think that’s a very good thing in terms of democratic health.”

But she said she thought some things had gotten lost — notably, that people who praised Kirk for civility were confusing the term with politeness. “Charlie Kirk was polite, which is about your mode of discourse,” she said. In her opinion, he was not civil because, she said, he excluded certain groups from the public sphere.

Despite the vitriol of the moment, Young said she was an optimist, thanks in part to what she has learned from public opinion research. “I know what people really want. Americans are sickened by these moments. By and large, Americans reject political violence.”

On Friday, after announcing the arrest of the man suspected of killing Kirk, Cox made an appeal to young people. Some of them loved the young activist, he said, and some of them hated him.

For his part, Kirk would say, “Always forgive your enemies; nothing annoys them so much,” the governor recalled.

“To my young friends out there, you are inheriting a country where politics feels like rage,” Cox said. “It feels like rage is the only option, but through those words, we have a reminder that we can choose a different path.”

“Your generation,” he added, “has an opportunity to build a culture that is very different than what we are suffering through right now.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

© 2025 The New York Times Company

Originally published on The New York Times