THE ECONOMIST: Baby boomers are loaded. Why are they so stingy?

They have amassed great wealth, but as baby boomers approach retirement they are being remarkably stingy.

Baby boomers were born between 1946 and 1964—and are the luckiest generation in history.

Most of the cohort, which numbers 270m across the rich world, have not fought wars. Some got to see the Beatles live.

They grew up during strong economic growth. Not all are rich, but in aggregate they have amassed great wealth, owing to a combination of falling interest rates, declining housebuilding and strong earnings.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

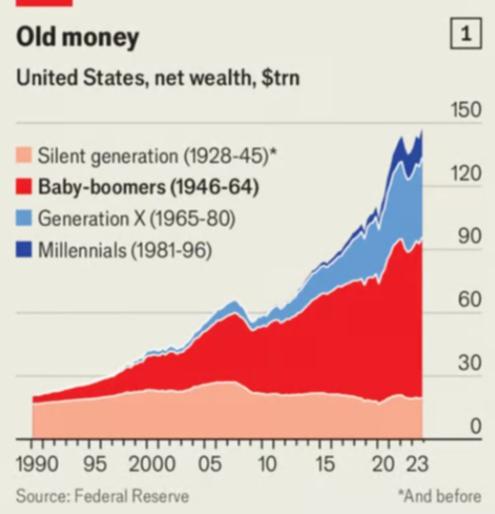

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.American baby boomers, who make up 20 per cent of the country’s population, own 52 per cent of its net wealth, worth $US76 trillion ($114t) as shown in chart one.

Now the generation is moving into retirement, what are they going to do with their money?

The question matters for more than just suppliers of cruises and golf clubs. Since they have deep pockets, boomers’ spending choices will exert a huge influence on global economic growth, inflation and interest rates.

It turns out boomers are remarkably stingy—not just in America but across the rich world.

They are not spending their wealth, but trying to preserve or even increase it. The issue for the economy in the 2020s and 2030s will not be why boomers are spending so much, as many had anticipated. It will be why they are spending so little.

Economists have a simple model of how people spend as they age. In youth, people’s outgoings exceed their incomes, as they borrow to invest in education or to buy their first house.

In middle age people accumulate money for retirement.

In old age they spend more than they earn, funding their lifestyles by selling capital (such as houses) and eating into savings.

Many researchers following such a “life-cycle hypothesis” argue that, as boomers retire, higher interest rates and inflation will result.

A growing number of free-spending boomers will demand goods and services from a shrinking pool of workers, leading to high wage inflation. As boomers shift from accumulating wealth to spending it, the global balance between savings and investment will shift, leading to higher interest rates, suggest Charles Goodhart and Manoj Pradhan, perhaps the most famous proponents of this view.

Yet recent evidence has cast doubt on the notion that a baby-boomer spending splurge is on the way. Italy and Japan, the world’s two oldest countries, have had low inflation and interest rates for years.

Academics point to the “wealth decumulation puzzle”, an observation that oldies spend down their lucre more slowly than the life-cycle hypothesis predicts.

One paper from 2019 by Yoko Niimi and Charles Horioka, two economists, notes that old people in Japan spend only 1-3 per cent of their net worth a year, meaning many die rich.

In the case of Italy, Luigi Ventura, another economist, and Mr Horioka find that 40 per cent of the retired elderly continue to accumulate wealth. Walk around any Italian town and the message is clear. Elderly Italians like to sit around chatting—and that’s free.

Our analysis suggests that the wealth-decumulation puzzle is becoming still more puzzling, for boomers are more miserly than previous generations.

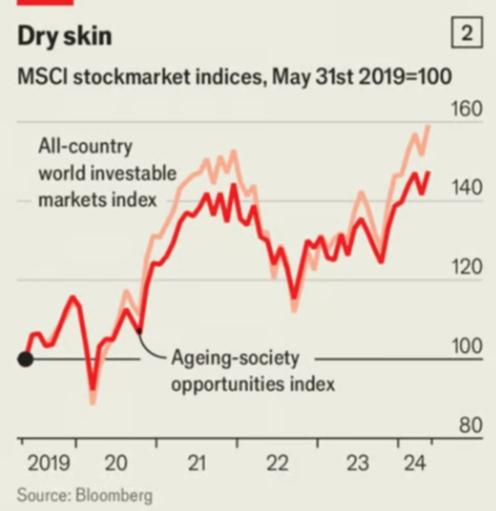

Some evidence comes from financial markets. Investment managers have created indices that track the share prices of firms that do well when oldies spend big.

One index produced by msci, a data provider, includes companies that provide treatments for age-related diseases, leisure and tourism, and anti-ageing skincare products. In the past five years, the index has underperformed the stock market, returning one percentage point less a year on an annualised basis (see chart two). Investors are betting boomers are hoarders, not splurges.

In the mid-1990s, those aged between 65 and 74 spent 10 per cent more than they took in, eating into their wealth. But since 2015 people this age have saved about 1 per cent of their income.

Boomers are also likelier than previous generations to say they save, suggests a survey by the Federal Reserve. In 1995, 46 per cent of retired households claimed to have saved in the past year. By 2022, 51 per cent of retired households did.

In Canada the saving rate of people over the age of 65 fell during the 2000s. But around 2015, after boomers had started to retire, the decline stopped.

More recently the rate has risen. In South Korea from 2019 to 2023 the saving rate of over-65s jumped from 26 per cent to 29 per cent, a bigger rise than in other age groups.

In Britain retirees are spending an ever-smaller share of what is coming in.

In Australia in the early 2000s, people over 65 saved next to none of their income. In 2022 they saved 14 per cent of it.

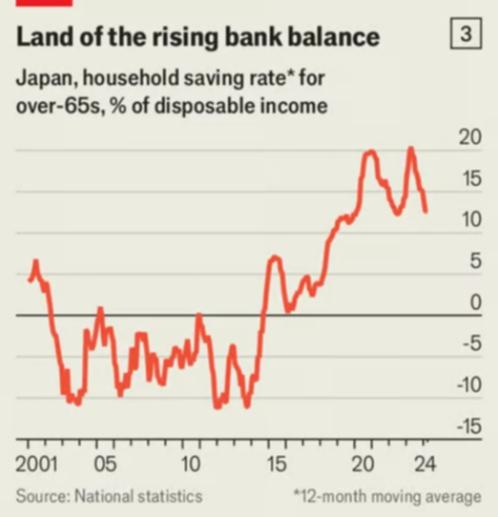

In Germany from 2017 to 2022 the saving rate for retired folk rose from 17 per cent to 22 per cent. And in Japan the old-age saving rate is soaring (see chart three).

Pensioners account for about 40 per cent of total consumer spending in Japan, less than they did a decade ago, even though there are far more of them.

Few boomers are downsizing to smaller homes, which would free up cash for the finer things in life. Empty-nest boomers own 28 per cent of America’s homes with three or more bedrooms, according to Redfin, a property firm.

Every self-respecting boomer has a spare bedroom. Indeed, in England about 20 per cent of all bedrooms are spare bedrooms. A spectacular apartment overlooking the Colosseum owned by Jep Gambardella, the 65-year-old protagonist of “The Great Beauty”, a film about Rome’s boomers, sleeps seven. Only Jep lives there.

At least he knows how to party

Perhaps boomers will stop hoarding. Many are healthier than their predecessors, which has allowed them to delay retirement and accumulate more wealth.

Across the oecd club of mostly rich countries, labour-force participation by people aged 55 to 64 recently hit an all-time high of 66 per cent, up from 58 per cent in 2011. Governments have introduced anti-ageism legislation, encouraging older people into the labour force.

Yet there could be deeper forces at play, making boomers reluctant to spend what they have earned, and in turn pressing down on interest rates and inflation. Three factors stand out: “bequest motives”, the covid-19 pandemic and worries about care.

Many boomers recognise how lucky they are to have accumulated such enormous wealth. They want to pass it on to their children, many of whom are struggling to buy a house or pay school fees.

Research by Messrs Ventura and Horioka, focusing on Europe, finds that bequest motives often go a long way towards explaining why retirees do not spend down their wealth.

It is difficult to measure whether boomers have stronger bequest motives than previous generations, though some evidence points in this direction. The flow of bequests from the dead to the living, as a share of gdp, is rising fast across the rich world. Americans inherit about 50 per cent more each year than they did each year in the 1980s and 1990s, for instance. Irish people inherit about twice as much.

Then there is the pandemic. Old people faced grave risks from covid. Many developed hermit-like habits, which they are struggling to shake off.

In 2022 American boomers spent 18 per cent less in real terms on dining out than they did in 2019. Bosses at Darden Restaurants, which runs chains including Olive Garden, a purveyor of pasta, recently noted that custom from people aged over 65 “is still below pre-covid”.

In Italy, another place that serves pasta, retirees’ spending on restaurants is falling fast. As you sip a negroni at a bar overlooking the Colosseum, you notice millennials, Gen X-ers and some Gen Z-ers. But where, if they are so rich, are all the boomers? Now they buy fewer experiences, many are accumulating wealth almost by accident.

The final factor is “longevity risk”. Many boomers will live to 100 and beyond, meaning lots will spend a third of their lives in retirement. This poses a financial burden, especially for those who may eventually need round-the-clock medical care.

According to research from the Employee Benefit Research Institute, a think-tank, in America the share of retirees who are very confident they will have “enough money in retirement” has fallen from more than 40 per cent in the mid-2000s to less than 30 per cent today.

These fears are changing behaviour. A study by the Institute for Fiscal Studies, a British think-tank, finds that those who believe they have “zero” chance of needing to pay for long-term care spend down wealth more quickly.

For the many people who worry about eventually losing their mobility or developing dementia, however, the risks of spending big today seem too great.

One paper from 2014 calculates that 13.5 per cent of aggregate American wealth is attributable to saving for old-age medical expenditures.

Ms Niimi and Mr Horioka, looking at Japan, arrive at an extraordinary conclusion.

Many Japanese retirees are not only saving for the cost of their own care, but also for the cost of their parents’, who are still alive. In an ageing world, taking care of the basics seems more urgent than enjoying drinks in front of the Colosseum.