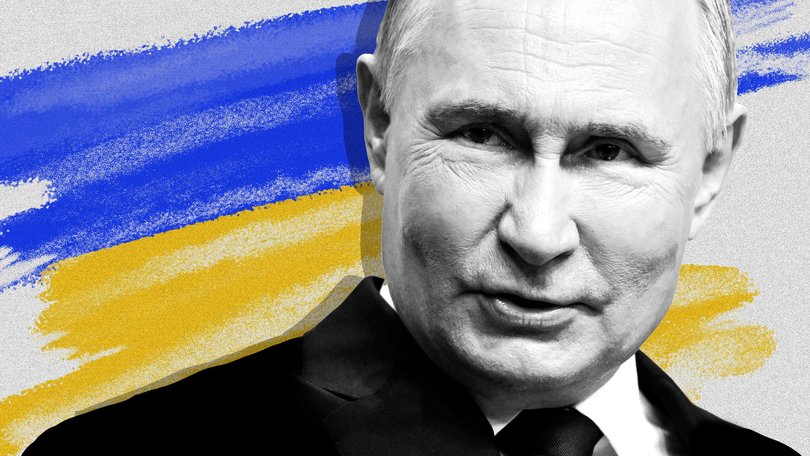

THE NEW YORK TIMES: Putin sees Ukraine through a lens of grievance over lost glory

THE NEW YORK TIMES: The Russian president has made it clear that his deepest concern is not the end of the bloodshed.

After all the presummit talk of land swaps and the technicalities of a possible ceasefire in Ukraine, President Vladimir Putin made clear after his meeting in Alaska with President Donald Trump that his deepest concern is not an end to three and a half years of bloodshed.

Rather, it is with what he called the “situation around Ukraine,” code for his standard litany of grievances over Russia’s lost glory.

Returning to grudges he first aired angrily in 2007 at a security conference in Munich, and revived in February 2022 to announce and justify his full scale-invasion of Ukraine, Putin in his postsummit remarks in Alaska demanded that “a fair balance in the security sphere in Europe and the world as whole must be restored.”

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Only this, he said, would remove “the root causes of the crisis” in Ukraine — Kremlin shorthand for Russia’s diminished status since it lost the Cold War with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the end of Moscow’s hegemony over Eastern Europe.

Putin didn’t directly mention the war, saying only that he “was sincerely interested” in halting “what is happening” because Russians and Ukrainians “have the same roots” and “for us this is a tragedy and a great pain.”

Casting Russia as the victim of the war it itself started has been a staple of Kremlin propaganda ever since Putin announced his invasion — described as a “special military operation” to save Russia — in 2022.

“Putin and Russia are revisionist; they cannot accept having lost the Cold War,” said Laurynas Kasciunas, the former defense minister of Lithuania, which until 1991 was part of the Soviet Union and has since joined NATO.

Also now in NATO are Poland, the Czech Republic, Romania and other former members of Moscow’s now-defunct military alliance, the Warsaw Pact.

Putin, Kasciunas added, never mentions the war and refers instead to the “situation around Ukraine” so as to “portray everything as a Western plot against Russia that merely uses Ukraine as a pawn and an instrument.”

Russia’s foreign minister, Sergey Lavrov, unsubtly signaled the Kremlin’s ambitions by arriving at his Alaska hotel wearing a sweatshirt emblazoned with the letters “CCCP,” Cyrillic for USSR.

But just before Putin and Trump met Friday, Poland gave Moscow a pointed reminder that the old order is gone by holding a parade of tanks and other military hardware, much of it American-made, along the Vistula River in Warsaw.

The display of military might, which also included a flyover of warplanes and helicopters, celebrated Polish victory over the Red Army in 1920 and showcased what is now the biggest military in the European Union.

In an apparent effort to salve Putin’s wounded pride over his country’s reduced post Cold War status, Trump, in an interview after the summit, with Sean Hannity of Fox News, inflated Russia’s position in the global hierarchy. Ignoring China and the European Union, he said: “We are No 1 and they are No 2 in the world.”

That, like that effusive welcome and applause given to Putin by Trump when he arrived in Alaska, went down well in Russia, where Kremlin-controlled media outlets and nationalist pundits rejoiced at what they saw as Russia’s readmission to the club of respectable and respected nations.

“I didn’t expect such a good result,” Aleksandr Dugin, a belligerent geopolitical theorist, said on Telegram. “I congratulate all of us on a perfect summit.

It was grandiose. To win everything and lose nothing, only Aleksandr III could do that,” he added, referring to the reactionary 19th-century czar who overturned the liberal reforms of his father.

Andrei Klishas, a nationalist senator who after the start of all-out war in Ukraine in 2022 said Russia should have contacts with the West only “through binoculars and gunsights,” said that the summit had “confirmed Russia’s desire for peace, long-term and fair” and left it free to carry out the special military operation “by either military or diplomatic means.”

Insisting that Russia has the upper hand on the battlefield and is “liberating more and more territories,” he added: “A new architecture of European and international security is on the agenda, and everyone must accept it.”

Exactly what this new architecture would look like is unclear, but its main pillar is the restoration of Russia to its Cold War position as a regional hegemon and global power treated as an equal by the United States, as it was at the Yalta conference in 1945.

Shortly before attacking Ukraine in 2022, Russia presented NATO and the United States with draft treaties demanding that NATO retreat from Eastern Europe and bar Ukraine from ever entering the alliance. These demands, which would reverse Russia’s Cold War defeat, were swiftly dismissed.

Putin, in a television address in 2022 announcing the invasion, focused not on Ukraine but on complaints about what he described as Western bullying and disregard for legitimate Russian interests and status.

“Over the past 30 years we have been patiently trying to come to an agreement with the leading NATO countries regarding the principles of equal and indivisible security in Europe,” he said.

“In response to our proposals, we invariably faced either cynical deception and lies or attempts at pressure and blackmail, while the North Atlantic alliance continued to expand despite our protests and concerns.”

A central part of Putin’s push to reshape the post Cold War order has been his effort to weaken or destroy the trans-Atlantic relationship created after World War II and expanded since 1991 with the admission to NATO of formerly communist nations in Eastern Europe.

On that score, the invasion of Ukraine has backfired, increasing NATO’s presence near Russia’s borders. Finland, which has an 830-mile border with Russia, in 2023 cast aside decades of military nonalignment to join the NATO alliance. Sweden also joined.

But Trump, who has blown hot and cold for months on supporting Ukraine, sowed discord in the alliance in Alaska by seeming to adopt Putin’s plan to seek a sweeping peace agreement in Ukraine instead of securing the urgent ceasefire he said he wanted before the summit.

The American president’s moves got a chilly reception in Europe, where leaders have time and again seen Trump reverse positions on Ukraine after speaking with Putin.

Echoing Russia’s line that Ukraine is a second-tier country whose interests cannot compete with those of Russia, he told Fox News: “Russia is a very big power, and they’re not.”

Whether the war ends, he added, depends on Ukraine and Europe, not the United States. “Now it is really up to President Zelenskyy to get it done,” he said. “I would also say the European nations have to get involved a little bit.”

Dmitry Medvedev, Russia’s hawkish former president, celebrated the summit for restoring “a full-fledged mechanism for meeting between Russia and the United States at the highest level” and showing that negotiations are possible between the two big powers “simultaneously with the continuation” of Russia’s military campaign in Ukraine.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

© 2025 The New York Times Company

Originally published on The New York Times