‘Fear worse than cancer’: Eyelid Merkel cell carcinoma survivor’s mental health battle amid husband’s death

When Patricia awoke from having facial surgery she received tragic news. She’s opened up about the worst part of her ordeal.

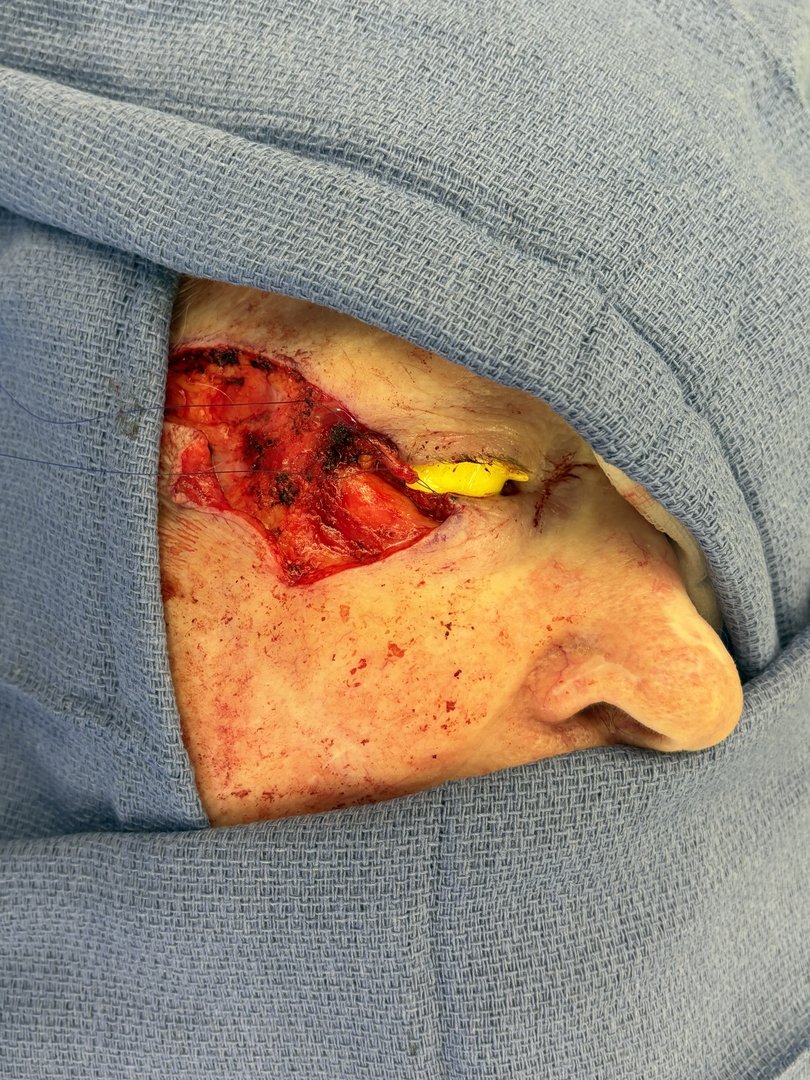

WARNING: GRAPHIC IMAGESWhen Patricia first spotted a small lesion rising on her lower eyelid earlier this year, she never imagined it would be the same “devil cancer” her high school science teacher warned about decades earlier.

The spot turned out to be Merkel cell carcinoma, one of the most aggressive forms of skin cancer, resembling “a little piece of broccoli... pushed up under and had all little seeds, sort of things on the top of it,” as she described it to The Nightly.

Patricia’s instinct to seek a second opinion likely saved her life.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Her GP initially dismissed it as no worry, but she persisted and showed a photo to plastic surgeon Dr David Sparks, who specialises in facial cancers. “This is a nasty one, and we’ve got to get onto it,” she recalled him saying.

“It’s got to be done, it’ll kill you.”

Within days, he operated, removing the disease and beginning a complex reconstruction that involved cutting out part of her lower eyelid and grafting flesh to restore it.

Patricia wanted to put off the surgery and treatment as her husband was in care at the time.

“I said my husband is in care and it is fading, so I can’t afford to have all my time taken up with surgery and everything that’s going to go with this, because, I can’t do that. I’m not doing that because I know I want to be with my husband when he passes.”

When she came out of surgery she was told very tragic news. “They told me that my husband had passed away. So it was just stress upon stress upon stress.”

Her husband Neil, a Vietnam War veteran who fought in the Battle of Alma Roll and battled PTSD for years, saw a psychologist. Patricia now sees the same psychologist every three weeks for breathing strategies to conquer her own fears, highlighting cancer’s profound mental toll.

Australia’s record as the world leader in melanoma cases continues, with incidence increasing from 54 to 63 per 100,000 people in the last five years. For many, surviving skin cancer is just the beginning of a long road to recovery, marked by fears like Patricia’s over visible scars and lost identity.

Dr Sparks eased some terror by delivering a smooth result: “You look better. You got rid of the wrinkles on that side,” people told her, praising his skill.

Twelve weeks on from her final treatment, Patricia awaits a full body scan in February, seeing a psychologist every three weeks for strategies to manage lingering fears.

“The biggest problem that I had to deal with was the fear... the fear of having the damn thing that I knew had to go,” she said.

“After being told I have beautiful eyes my whole life. I thought here goes. It’s always awful to have something on your face like that.

Patricia’s story is part of a larger Australian health challenge: nearly three-quarters of cases occur in visible areas such as the face, neck, and hands, regions that shape identity as much as appearance.

While early detection has lifted survival rates, 95 percent of people with stage I melanoma now live ten years or more, doctors warn that recovery doesn’t end once the tumour is removed, with 39 percent of head and neck cancer patients facing lasting functional impairment and visible scarring contributing to anxiety.

Dr Sparks, who leads The Coastal Clinic, says reconstructive plastic surgery is an essential but still misunderstood part of cancer care. “The perception is that treating skin cancer is just about removing the skin lesion itself, but that’s really only the first step,” he says.

“At our practice, we use a tailored approach for each cancer patient to give them the best functional and cosmetic outcome for the cancer surgery. For more complicated cases, we’re now using 3D-printed facial frameworks and custom implants that help us to plan surgeries with high levels of precision – this all gives us the ability to help people feel like themselves again.”

A meta-analysis of more than 500 people with facial palsy found that 95 percent regained movement and improved quality of life after reconstructive surgery, evidence Dr Sparks says, that “plastic surgery plays a vital role in helping patients heal completely, not just physically, but also functionally and emotionally.”

For 85-year-old Patricia healing means confronting denial head-on. She laid across her husband’s body after he died, hugging him with family to process the loss without illusion.

“He was lying there, so I made sure that I wouldn’t be going through any denial. So I just lay across him and put my arms around him,” she said.

Originally published on The Nightly