From data breaches to divorce: Why Australians are desperate to delete their online presence

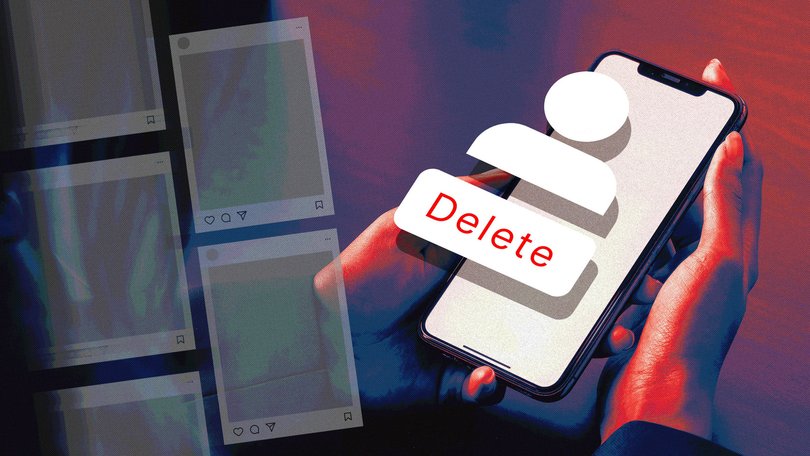

Experts say it’s impossible, but erasing your online presence emerges as the new form of self-defence amid a global urge to ‘disappear’ online.

When Emma separated from her husband, she decided to confront something she had long taken for granted: how visible her life was online.

Last year, the Melbourne-based mother of three was navigating divorce, relocation and a career pivot.

Emma — who asked that her surname not be published — moved from a public-facing role where a LinkedIn profile felt mandatory into a government position where discretion was expected and social media activity was discouraged.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.“I felt so vulnerable and exposed when I was going through my divorce,” she said. “After that, I wanted a fresh start and to reclaim my privacy. Separating presented an opportunity for me to take back control.”

Setting up a new home as a single mum became a reset point. Emma downsized from a house to an apartment for greater physical security, set up a PO Box, created a new email address and deleted her social media accounts.

“There were still visible comments, likes and photos I’d shared more than a decade ago,” she said. “I’m not even friends with half of the people in those photos anymore.

The 46-year-old was also keen to keep her address and financial information private, wanting to step away from the ease with which property purchases and personal milestones can be scrutinised online.

Emma’s experience reflects a broader shift that cybersecurity and privacy experts say is accelerating in Australia: a desire to disappear. Even if not entirely, but to become less searchable, less exposed and harder to profile.

The fantasy of total erasure

Cybersecurity expert Arash Shaghaghi says the idea that a person can fully delete themselves from the internet is a myth.

“Once you connect to the internet and begin using services (for example, signing up for social media, shopping online or even just browsing), total digital erasure becomes a fantasy,” he said.

“In the digital world, your data isn’t a single object in a single place. It’s more like copies of copies, scattered across systems you’ve never heard of.

“Most Australians don’t realise that their digital self is spread across hundreds of different legal jurisdictions and thousands of servers. There is no central ‘Off’ switch because there is no central ‘On’ switch.”

Associate Professor Shaghaghi, from the University of New South Wales, said much of this data is generated passively, often without people realising how much they are sharing or how widely it travels.

“When you browse a website, your IP address, location and behaviour are quietly collected through cookies and trackers,” he said. “And most of us make this even easier by clicking ‘Accept All’ on cookie consent pop-ups without reading what we’re agreeing to.”

Once data crosses borders, Australian protections can evaporate. “What’s protected under Australian law may not be protected in another country,” he said. “Once that happens, your data is no longer meaningfully under your control.”

“You can reduce your visibility, but you cannot delete your existence.”

Why Australians are seeking privacy — not invisibility

Darren Whiteman, director of Hunterwhite Recoveries & Investigations, says most local clients are not trying to disappear entirely.

“In Australia, most people seeking digital footprint security are not trying to ‘disappear’,” he said. “They are responding to a moment of increased visibility, risk or transition.

“Common triggers include career changes into leadership or regulated roles, safety concerns following harassment or stalking, family law matters, relationship breakdowns, or becoming more publicly visible through business ownership, litigation, or media exposure.

“We also work with families who are reassessing what information about their children, routines, and locations is available online.”

One of Hunterwhite’s privacy protection services – elite digital footprint security – is designed to help Australian understand, reduce and manage their online exposure.

“At a high level, our work focuses on identifying where a person or family is unnecessarily exposed and advising on how to reduce that exposure lawfully and realistically,” Mr Whiteman said.

“Some clients come to us after something has gone wrong — harassment, impersonation, unwanted attention, or a data exposure. Others are proactively reassessing their footprint before stepping into a new role, launching a business, or increasing public visibility.

“We don’t promise erasure. We focus on risk reduction, accuracy and control.”

Demand increasingly comes from professionals in sensitive industries.

“We see high demand from executives, legal and financial professionals, health workers, educators and people in sensitive industries where unmanaged exposure can carry real-world consequences,” Mr Whiteman said.

“Often the trigger is a realisation — sometimes after an incident — that their digital footprint no longer reflects who they are, or exposes more than it should.”

Safety, not vanity

For high-risk clients, privacy is less about reinvention than survival.

Global privacy, protection, and reputation management firm havenX is known for providing “extreme privacy” consulting services for high-net-worth individuals.

“People with bearer assets, especially those in crypto are a big market segment given the rise in physical attacks and ‘$5 Wrench Attacks’ (home invasions and attacks to procure crypto coins),” CEO Alec Harris told The Nightly.

“Highly visible executives in general are a target so we see demand across sectors but the more controversy or digital value in a sector the more likely it is to be a target for threat actors.”

Mr Harris says most requests for extreme privacy are driven by safety, not image management.

“It’s almost always safety. We’ve only ever had a few reinvention inquiries and we are wary of them since they could be covers for criminal activity,” he said.

“We do see people asking for reputation management but that is more of a reputational rehabilitation effort than an obfuscation/privacy effort.

“Sadly, we get a lot of clients who come to us with exigent circumstances. It’s extremely costly at that point to counter the threats.

“Starting left of attack is an order of magnitude less expensive, not to mention preventative. Many people think ‘it won’t happen to me, I’m not that interesting’ and that can be true, until it isn’t.”

Why women are more exposed

Online risk is not evenly distributed with women facing greater exposure and vulnerability online.

“Women are more frequently impacted by harassment, stalking, impersonation and unwanted contact, and often seek privacy measures earlier and more defensively,” Whiteman said.

“This shapes the advice we give, with greater emphasis on safety, boundary-setting, and reducing exposure pathways that others might overlook.

The aim is not to limit participation online, but to enable people — particularly women and families — to engage more safely and confidently.

Dr Shaghaghi said there was a clear distinction between privacy and safety.

“For a significant portion of the population, a digital footprint is a direct liability,” he said.

“For survivors of domestic and family violence, every piece of their digital footprint… is a clue that an abuser can use to track them down.”

“When a home address is leaked, the psychological and financial cost is immense, sometimes requiring victims to move house or hire physical security.

“We need to stop viewing ‘deleting yourself’ as an act of vanity or paranoia,” he said. “For many Australians, digital erasure is a form of digital self-defence.”

Why Australia is different & similar

Australia has relatively strong privacy laws and fewer openly accessible commercial “people search” databases than the US.

“However, Australians frequently underestimate how much personal information is still visible through everyday systems — business and professional registers, electoral exposure, licensing databases, historical media reporting, workplace bios, sporting clubs, school communities, and informal social media sharing,” Mr Whiteman said.

“The result is that exposure here tends to be fragmented rather than centralised.

“Privacy work in Australia is therefore less about mass removal and more about understanding how information accumulates, where unnecessary visibility exists, and how different data points can be linked together.”

Whiteman said demand for privacy services in Australia is steadily increasing.

“Data breaches, scams, increased online hostility, and changes in how people work and live online have all contributed,” he said.

“There is growing awareness that digital exposure isn’t abstract — it affects safety, reputation, and opportunity — and that prevention is far easier than remediation.”

A global shift toward privacy

The desire to reduce online visibility is not an isolated or local phenomenon.

“Demand is absolutely up.” Mr Harris says. “Privacy is becoming a core pillar of corporate security programs and, while I’m clearly biased, it has some social cache in certain circles as well.”

Mr Harris says repeated cyberattacks and data breaches have played a significant role in shifting public attitudes.

“Story after story about the security breaches that start from digital exposure have worked their way into the collective consciousness,” he said.

“People realise this is a problem and some are ready to do something about it.”

Importantly, Mr Harris rejects the idea that managing a digital footprint requires retreating from public or professional life.

“It does not mean you can’t be a keynote speaker at a conference or build a reputation in your domain,” he says.

“It does mean that people might be able to find you for your expertise but not necessarily know where your kids go to school and how much your house is worth.”

That distinction — between professional visibility and personal exposure — is increasingly central to how people think about privacy.

“It means you decide what to share, rather than being a victim of collection,” Mr Harris says.

Mr Harris says Australia reflects the same broader pattern seen overseas, with individuals like Emma becoming more alert to how much information about their lives is publicly accessible — and more willing to take steps to regain control.

A quieter life without vanishing

Emma knows she cannot erase herself entirely. Court records, electoral requirements and professional systems make that impossible. But the process of tightening her digital footprint has already improved her mental health.

“So far I’ve deleted social media accounts and requested to have photos of me taken down,” she said. “I still have a lot of work to do but starting this process has felt empowering.”

“It has given me peace of mind and a sense of freedom, headspace and privacy that I haven’t felt in years,” she said.

“This is one step in regaining control of my privacy, boundaries, safety and life.”