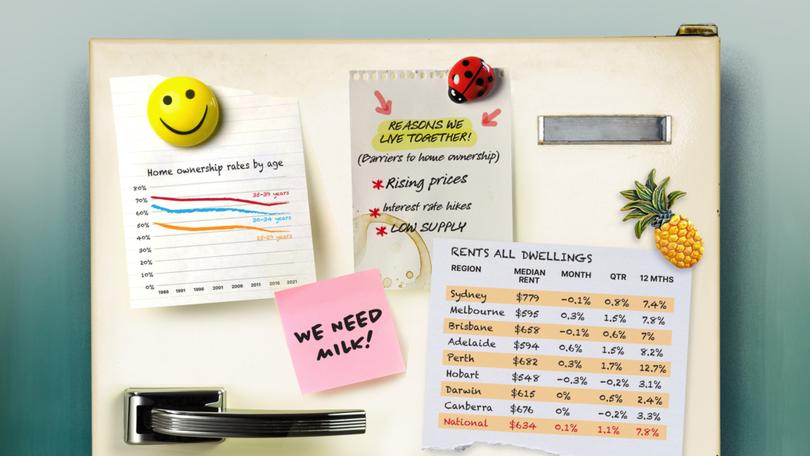

Great Australian Plight Part Two: How the rental nightmare is putting home and family plans in limbo

Part two of The Nightly’s special series looks at how the accommodation crisis is keeping more Australians in sharehouses as their plans to start families in their own homes slip further out of reach.

The soaring price of renting and buying property is forcing Australians to stay in shared accommodation longer and delay the purchase of their own homes and even plans to start families.

About 56 per cent of prospective tenants seeking a room in a rental property are aged between 25 and 44, according to data from REA Group’ share house platform Flatmates.

Meanwhile the average median weekly rent in Australia jumped 7.8 per cent over the past 12 months to $634, according to CoreLogic figures, with Perth and Adelaide copping the highest increases with 12.7 per cent and 8.2 per cent respectively.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Prices in Sydney and Melbourne, the nation’s most populous capitals, have increased by 7.4 per cent and 7.8 per cent respectively over the past year but have slowed over the past three months to 0.8 per cent and 1.5 per cent.

CoreLogic economist Kaytlin Ezzy said the earlier skyrocketing rents were due to a rush of overseas migration when Australia reopened its border after COVID, which, coupled with inadequate rental supply, pushed prices up by 40 per cent over the past five years.

Ms Ezzy said the growth in rental prices had eased as migration slowed while renters had reached the limit of what they could pay, with some moving into share houses in an effort to pay the bills.

“They have to find other means to make it more affordable once they have reached their limit, either by moving further out to more affordable outer rental markets or to the regions,” she said.

“But also forming larger households, so reforming households that maybe were split up over the COVID period as a way of sharing that excess rental burden across more people.”

Renting is more precarious than home ownership and subject to varying state and territory laws that are enforced with mixed success.

NSW Greens housing spokesperson Jenny Leong said Sydney’s property market was “cooked”, adding that a range of people including millennials, low and medium-income earners, older women and families with kids were increasingly stuck in rentals for longer.

“In a virtually unregulated rental market, lifetime renters face tough choices around having kids in an insecure rental where getting kicked out or priced out could mean uprooting kids from their school and community,” she said.

Filmmaker Freyja Benjamin, 35, is looking for a new share house after the landlord of her current rental asked her and her housemates to move out after he had earlier agreed to let them stay for an additional six months at their Annandale rental in Sydney’s inner west.

“We actually asked our landlord, who we pay in cash, if we could stay for another six months a month ago,” she said.

“Eventually he responded, ‘Sure I don’t have any plans for the house’.

“Then on Friday night at 7.30pm he said, ‘Actually you have leave in 30 days’.”

Ms Benjamin said she likes living in share houses, although her recent searches had yielded depressing results. She also said her sister was struggling to find her own accommodation.

“She was looking and would like to live on her own but it’s not really viable on her salary and she’s a teacher at high school,” she said.

“But it would be just a huge jump in rent and she’s not able to save much as it is.”

The NSW Labor government is due to introduce legislation banning no-grounds and no-fault evictions into state parliament next month in a bid to increase rental security.

The increasingly long time spent in rentals and shared accommodation is also influencing other aspects of people’s lives, including when — and if — to start a family and have children.

The Productivity Commission has warned Sydney risks becoming the “city of no grandchildren” while KPMG analysis released last month found the number of births in NSW in 2023 dropped by 6.4 per cent compared to the previous year.

The number of births in the Greater Sydney region has fallen about 14 per cent since 2018. Births for that region dropped from 70,400 to 68,600 last year alone.

Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute managing director Michael Fotheringham said young people were delaying forming households of couples and having children because they were struggling to purchase or rent a home.

“If people can’t secure appropriate safe, suitable housing then they are less likely to form new households and to have children, that’s clear,” said Dr Fotheringham.

“Our birth rate is not enough to maintain our population and in terms of thinking of the workforce that’s required to look after our ageing population and also the taxbase to finance their services.

“That’s a real worry. The population, the shape of our ageing population is looking pretty alarming.”