Building Billions: Warren Anderson took the eastern states with the help of formidable 1970s union bosses

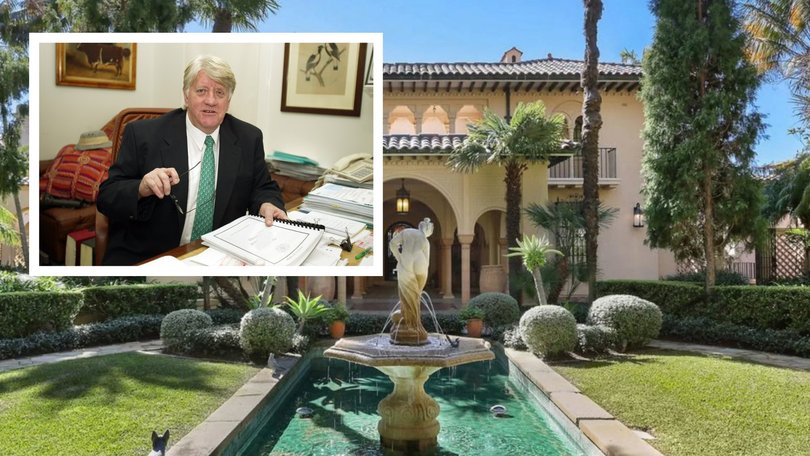

From his small, rented apartment in Sydney’s Rushcutters Bay, one-time Perth business tycoon Warren Anderson can only shake his head at the recent $80 million sale of the prized waterfront mansion he once called home.

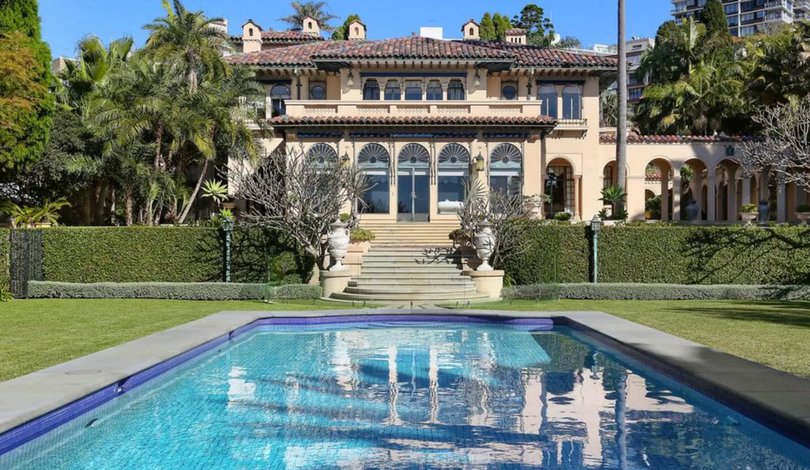

Known as Boomerang, Mr Anderson bought the trophy estate on Sydney’s Elizabeth Bay for $3.5 million in 1985. He lived there for eight years, entertaining the likes of aspiring prime minister Paul Keating and his then-wife Annita, Packer family matriarch Ros Packer and the late entertainer Barry Humphries, before his bankers seized the property and sold it for less than $6 million in a mortgagee fire-sale in 1993.

“I bought Boomerang in 1985 for $3.5 million and they flogged it on me for less than six,” lamented Mr Anderson, the godfather of the Keatings’ youngest daughter. “And then it went through various owners and (trucking billionaire) Lindsay Fox has just sold it for 80.”

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.With all its historic grandeur and social status, Boomerang was symbolic of how Mr Anderson succeeded where many other West Australian businessmen have come unstuck: breaking into the eastern states market.

In doing so, the former shearer, bulldozer driver and roadhouse operator — who was once described as having hair as blond as Paul Hogan’s and a face as hard as Hulk Hogan’s — helped shape the national expansion plans of two of Australia’s better known companies, retail giant Coles and construction group Multiplex.

Now, at the age of 83, Mr Anderson has given a rare and fascinating insight into just how he went about doing that some 47 years ago.

By the time he arrived in NSW in the late 1970s, Mr Anderson had developed no fewer than 28 suburban shopping centres and stand-alone supermarkets in Western Australia for the company then known as GJ Coles & Co and its Kmart retail offshoot. His builder of choice was Multiplex, the family company founded by the late Perth billionaire John Roberts.

As Mr Anderson tells it, most of those shopping centres and supermarkets were built under what was effectively a handshake funding arrangement between Mr Anderson’s private company New World Developments and Coles which he described as “gold.”

“All up, Coles gave me over a $1 billion in guarantees to build shopping centres and stand-alone supermarkets,” Mr Anderson said.

“Coles used to sign a development guarantee which, if something went wrong , they’d front up with the money. But nothing ever did go wrong.

“That was gold in my hands and gold in the hands of the merchant bankers I used, Trans City Holdings.”

Likewise, Mr Anderson’s close friendship with WA Builders Labourers Federation (BLF) state secretary Kevin “God” Reynolds was also gold for him and Mr Roberts, effectively guaranteeing industrial peace on his Perth construction sites.

By 1978, Coles was keen to replicate that growth across the Nullarbor in New South Wales to expand its national footprint under the same successful model it had used in WA.

Problem was, in the construction game, NSW was a much tougher ‘hood for upstart developers and builders from the west like Mr Anderson and Multiplex.

For starters, the BLF in 1970s Sydney had a reputation for being the most militant trade union in Australia, often using controversial “green bans” to boycott construction projects on community or environmental grounds.

What’s more, Coles would have to break the eastern states stranglehold of its formidable rival, Woolworths, which was already well-established in NSW.

“Coles asked me to come over here (Sydney) because they couldn’t get into NSW because Woolworths had a grip on the developers over here and also the financiers too,” Mr Anderson said.

“They (Coles) only had a few supermarkets in NSW until I got here because Woolworths used to keep them out. And they had no show of getting in here until I arrived.”

At the time, one larger-than-life figure cast an intimidating shadow over construction sites in the eastern states: the BLF’s all-powerful Melbourne-based national secretary Norm “The General” Gallagher.

A renown street fighter in his youth who went on to do a stint of tent boxing, the late Mr Gallagher had a reputation as a “don’t argue” union leader. Depending on what side of the picket line you sat, he was considered either Australia’s most notorious unionist or a working class champion who fought hard — on occasion with his own knuckles — for better wages and working conditions for his members.

Mr Anderson figured that if he wanted to do business in NSW, he needed to win over Big Norm. So he called on Mr Reynolds for a favour.

“Kevin Reynolds was the boss of the BLF in Perth and he introduced me to Norm Gallagher,” Mr Anderson said.

“I went to see him (Mr Gallagher), I fronted up to him, I told him what I was going to do and when I was going to do it — and that I was looking for a BLF umbrella to get under. And from there on, we were best mates.

“Norm operated out of Carlton and my architect, Mario Bernardi, he also lived in Carlton. In fact, they were in the same street, Drummond Street. It was like a little club we had.

“Norm was very good, he was a great fella and for some reason or another, he just liked me. The fact of the matter was I was creating work for his members.”

“And over the billions of dollars in property I developed, he never asked me for one cracker — he never put his hand out one instance.”

With Mr Gallagher in his corner, Mr Anderson arranged a meeting with the BLF’s firebrand NSW state secretary Steve Black at Trades Hall on the edge of Sydney’s Chinatown in December 1978 to introduce his builder, Mr Roberts.

“I can remember Johnny Roberts … wanted me to introduce him to the BLF over here,” Mr Anderson said. “And the BLF was run by a young fella by the name of Stevie Black, who was the boss here in NSW. And Stevie Black was a prickly bastard in those days.

“And I said ‘yeah, sure, I’ll introduce you’.

“So I took him (Mr Roberts) down to Goulburn Street in Chinatown and introduced him to Stevie Black. And when Johnny Roberts came into his office … I said ‘hello, this is John Roberts, he hopes to start up here in NSW.’

“And he (Mr Black) said ‘oh yeah.’ And he looked at Johnny Roberts and he said ‘listen, you (expletives deleted), sit down in the corner and I’ll be with you in a minute.’

“And John wasn’t used to being spoken to like that. Anyway, he sat down in the corner and didn’t say a word. And it was a good 10 or 15 minutes before Black said ‘all right, what can we do for you?’

“He (Mr Black) knew my power with Norm Gallagher at the time and he blessed Johnny Roberts into coming into NSW. If the bosses of the individual states didn’t do as they were told by Norm Gallagher, they’d get removed very quickly.”

Despite those undertakings, things didn’t start well for the two WA interlopers in Sydney, with Mr Black’s BLF shutting down work on their very first Coles shopping centre, Northgate in Hornsby, by declaring a green ban on the construction site.

Enter the hand — or at least the gnarled finger — of Big Norm.

Anderson was a physically tough and intimidating man; qualities he used to his advantage when he clashed with (John) Roberts

“The BLF back then were very, very militant,” Mr Anderson said. “And, of course, the green ban they had on Hornsby was lifted off the site in quick time because Norm just put his finger on it and said ‘Aye, just lift this green ban’.

“He was the national president and the state bosses of the BLF, they used to take notice of him.

“That’s why I got a clean run right through a lot of the work that was done over the years. There were never any strikes on any of our sites.”

That industrial peace enabled Mr Anderson to develop another 24 shopping centres and free-standing supermarkets for Coles throughout NSW — and another four more in Victoria and Queensland. All up, including Western Australia, that made for a national total of 56 during what was a lucrative 15-year partnership with Coles.

“Those shopping centres established Coles as the leading supermarket operator in Australia and was the basis for their dominance in the marketplace,” he said.

The Coles partnership was also a launchpad for Mr Anderson and Multiplex to step up into commercial property, developing a string of office towers worth an estimated $1.3 billion in Australian capital cities under a partnership with the late media mogul Kerry Packer. While highly lucrative to start with, Mr Anderson’s partnership with Mr Packer would ultimately lead to the unravelling of his debt-heavy private balance sheet, starting with $50 million lost in the infamous bail-out of the late Laurie Connell’s merchant bank Rothwells in 1988.

While he worked closely with Mr Roberts for many years, Mr Anderson’s unconventional way of resolving disputes was on public display one evening at Perth’s Sheraton Hotel, as revealed in former WA Premier Brian Burke’s autobiography A Tumultuous Life.

“Anderson was a physically tough and intimidating man; qualities he used to his advantage when he clashed with (John) Roberts,” Mr Burke wrote.

“Once, an anonymous but leading member of Perth’s business elite had arranged to meet Roberts for a drink at the Sheraton Hotel in Perth.

“When he got there, he saw a big crowd at one end of the lobby watching Anderson applying a punishing headlock with an occasional right jab to Roberts, demanding he make good on overcharging Anderson for a shopping centre he’d built.

“Eventually, Anderson extracted a promise from Roberts that he’d give him a cheque the next day and the brawling stopped. Then everyone had a drink.”

Asked about the accuracy of Mr Burke’s account of the Sheraton incident, Mr Anderson said he didn’t dispute it, adding: “But I don’t know who the member of Perth’s business elite was.”

Multiplex’s success made its founder Mr Roberts a billionaire by the time he died in 2006 at the age of 72. A year later, his children, Andrew, Tim and Denby, pocketed a collective $1.1 billion for the family’s controlling shareholding when Canada’s Brookfield Asset Management bid $4.3 million for what was by then an ASX-listed company.

“When they sold Multiplex, they wouldn’t have been able to sell it to Brookfield in Canada if it wasn’t for that introduction into the BLF,” Mr Anderson said. “Because they could make or break you in those days, the BLF.”

Meanwhile, it was during Mr Anderson’s shopping centre heyday that he first crossed paths with budding billionaire Lindsay Fox, who was also expanding his private Linfox trucking business into NSW on the back of a lucrative contract with Coles.

“His old trucks would drive around to the Coles New World supermarkets, like the Hornsby shopping centre, to the loading dock to offload the groceries that were going to be sold in the supermarket,” Mr Anderson said.

“I was aware of him and of course he was aware of me, and he was following me around with the shopping centres. He was well and truly in with Coles.”

As it turned out, Mr Anderson and Mr Fox would share the same taste in waterfront mansions, with both owning Boomerang during different eras.

Mr Anderson hadn’t originally intended to live in the Elizabeth Bay mansion. When he first moved to NSW, he bought two adjoining houses in upmarket Vaucluse with sweeping views across Sydney harbour, where he often hosted Mr Gallagher.

His plan was to demolish them to build a mansion — similar to what Pankaj and Radhika Oswal planned to do decades later on Mr Anderson’s Peppermint Grove superblock with their controversial $70 million “Taj Mahal on Swan” mansion.

However, when Boomerang came up for sale in 1985, Mr Anderson jumped at it, paying $3.5 million for what would be the first of his trophy properties.

The same year, after a lengthy retrial, Mr Gallagher was jailed on charges stemming from a royal commission into the building industry, which reportedly played a big part in the Hawke Government’s move to deregister the BLF in 1986.

Not surprisingly, Mr Anderson reckons his mate was hard done by.

“He (Mr Gallagher) got a few lousy leftovers he took off a construction site to build his holiday home and they nailed him for that,” he said. “As far as I know, they never actually caught him reefing money off people.”