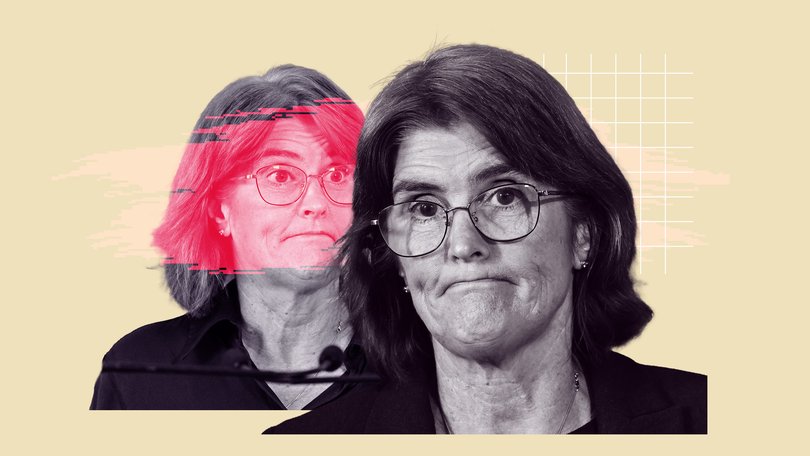

Interest rates: Critics pile into Reserve Bank governor for ‘wimping out’

Economists lined up to attack the board for being too slow to raise rates, accusing it of protecting mortgage borrowers and the Labor Government.

Reserve Bank Governor Michele Bullock sent mixed messages to investors on Tuesday when she insisting the bank is serious about getting inflation back to its 2.5 per cent target at the same time as forecasting it won’t happen until at the least second half of 2028.

Ms Bullock denied she’s let inflation become entrenched since taking the role in September 2023.

“We don’t think it’s become entrenched, but it’s a higher rate than we’re comfortable with and that’s why the board has raised today,” she said at a press conference after raising rates for the first time in over two years.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.“The board felt if it didn’t raise today it would be signalling a tolerance for inflation above target, and that’s not the message they want to give.”

On Tuesday the RBA raised interest rates 25 basis points to 3.85 per cent, which preceded an aggressive series of three rate cuts between February and August 2025 to the delight of the Labor government and mortgage holders.

Economists criticise central bank

Economists lined up to attack the board for being too slow to raise rates, accusing it of protecting mortgage borrowers and the Labor Government.

“The RBA wimps out. It’s scared to do its job,” declared Peter Tulip, the chief economist at the Centre for Independence Studies.

EQ Economics Managing Director Warren Hogan said: “The RBA has all but admitted that they have not controlled inflation.”

Mr Hogan, a consistent critic of the RBA, declared it “failed the test of economic leadership”. Prices have soared around 25 per cent in aggregate since the pandemic-era of government spending supported by too easy monetary policy.

Elsewhere, former RBA economist Zac Gross suggested that unless Ms Bullock and her board get more aggressive in containing inflation then they might get a reputation for putting off the problem.

“Today we had one hike. The RBA forecasts that even with two more hikes we will still miss the inflation target at the end of horizon (June 2028),” Mr Gross wrote.

Politics and productivity

At the media conference, journalists peppered the governor with questions about whether the board was being pressured not to criticise the Labor government for contributing to inflation.

“I’d like to know has anyone in the Albanese Government told you, or anyone in the RBA to your knowledge, not to comment on their spending?” asked one journalist.

“No one has made that comment to me,” she fired back. “And the board, obviously, makes its decisions independently of the government.”

The tension between Labor’s spending and immigration policies and the board’s battle to control inflation was repeatedly raised at the press conference.

The governor pointed back to weak productivity as a shared national problem that stokes inflation.

Low productivity means Australia is producing less with more people. This outcome creates more demand for the same amount of output in goods and services to equal price inflation. Every time economic growth heats up the productivity trap is amplified.

Australia then is back to the problem of the Government’s foot being on the economic accelerator, while the central bank applies the brakes.

Markets are now pricing at least one more interest rate increase in 2026, with a reasonable possibility of two more taking rates back to 4.35 per cent at the same level as the top of the last cycle just over two years ago in late 2023.

The RBA will deliver its next monetary policy decision on March 17. Most economists now expect the next interest rate increase to come at its May meeting.