THE ECONOMIST: As oracle Warren Buffett exits, Greg Abel faces uphill battle leading Berkshire Hathaway

THE ECONOMIST: Now that Warren Buffet has finally retired, his successor faces an uphill battle

The first time he “retired”, in 1956, Warren Buffett was 25. Benjamin Graham, the famous stock-picker who employed him, had closed his fund.

The oracle of Omaha, as Mr Buffett would later become known, went home to Nebraska. His break from work was brief; he soon started an investment partnership of his own.

But then in 1969, aged 38, Mr Buffett retired for a second time, telling investors he was “not attuned to this market environment” and would shut down his fund.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.His attention shifted to Berkshire Hathaway, a struggling textile concern he controlled. It has since been among the greatest successes in the history of business.

On December 31, Mr Buffett, who is 95, retired for a third — and presumably final — time, leaving his role as chief executive of America’s ninth-most-valuable company, and its most unique.

Berkshire is a financial colossus. It is America’s second largest property and liability insurer, and holds tradeable stocks, bonds and cash worth nearly $US700 billion. It is also an industrial conglomerate. Berkshire controls around 200 companies including BNSF, one of four “class 1” railroads in America; a collection of power utilities; and consumer brands from Brooks running shoes to See’s candy.

It is a capitalist religion, too. The 1934 edition of “Security Analysis”, a textbook by Mr Graham and David Dodd, is its bible. Sermons are delivered annually by Mr Buffett at Berkshire’s shareholder conference.

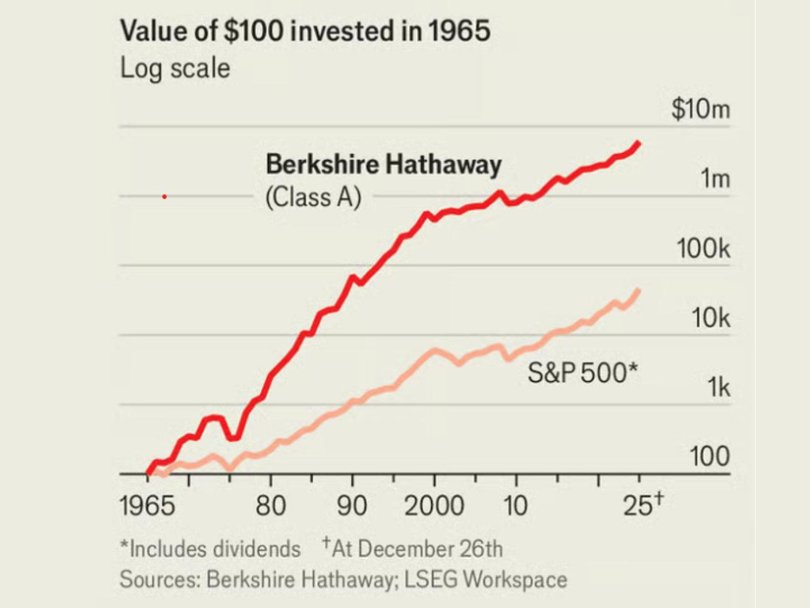

It is hard to imagine a tougher act to follow. Sprawling, analogue and fraternal, Berkshire is a singular company that long revolved around its singular boss. He has been wildly successful: since Mr Buffett took control in 1965 Berkshire’s shares have trounced America’s S&P 500 index (see chart).

The transition to Gregory Abel, his anointed successor, will thus be closely watched. Can Mr Buffett’s creation continue to thrive after he steps aside?

America’s most revered company is also one of its least well understood. Berkshire is known as a vessel for Mr Buffett’s investing genius. He is a “value” investor insofar as he began his career scouring markets for companies worth less than the accounting value of their assets. But he has also owned plenty of “growth” stocks.

His purchase of Apple shares between 2016 and 2018 was among the most profitable investments in Berkshire’s history. Mr Buffett dislikes both terms. But one piece of investment jargon he can’t talk about enough is “moats” — a competitive advantage that allows a business to consistently earn a rate of return above its cost of capital. Mr Buffett’s knack for spotting them is one reason for Berkshire’s remarkable performance.

Some moats are bestowed mainly by the tastes of consumers, as in the case of Apple (Berkshire owns stock worth $US65 billion) or Coca-Cola ($US28 billion). Others are conferred, at least in part, by regulation, as with Bank of America ($US32 billion) or Moody’s ($US13 billion). Berkshire owns a sliver of both Visa ($US3 billion) and Mastercard ($US2 billion), America’s dominant credit-card providers, as well as a fifth of American Express ($US58 billion).

Perhaps Mr Buffett’s greatest innovation, however, was not in allocating capital, but raising it. In 1967 Berkshire bought National Indemnity, a Nebraskan insurer.

Together with GEICO, a car insurer, and a large reinsurance business, it provides much of Berkshire’s capital.

The idea is simple. Policyholders pay premiums to insurers before insurers pay claims to policyholders.

When an insurer is run profitably, collecting more in premiums than it pays in claims and costs, it can invest those premiums and pocket the returns.

Most insurers park them in bonds. Private-equity-owned life insurers now experiment with buying higher-yielding private debt. But, unusually, half of the assets held by Berkshire’s insurance arm are invested in a concentrated portfolio of stocks.

Underwriting profits from Berkshire’s insurance business make up a small and volatile part of its bottom line, but the premiums collected have funded some huge deals.

BNSF was owned first by National Indemnity before it became a directly held subsidiary of Berkshire in 2023. The quarter of Occidental Petroleum Berkshire owns is also housed by the insurer.

Another spigot of capital mastered by Mr Buffett is retail investors. Berkshire’s annual meeting is a jamboree of adoring middle-class capitalists. It is the opposite of the gambling-adjacent retail trading which drives markets these days, but just as fun. Berkshire’s meeting in 2015 began with a video of Mr Buffett pretending to box Floyd Mayweather. There are also newspaper-tossing competitions — though Mr Buffett tossed print publications out of his portfolio in 2020.

Berkshire now has plenty of imitators. Bill Ackman, a brash hedge-fund manager, says he is building his own version at Howard Hughes, a real-estate firm his fund owns half of.

But what does Berkshire’s own future hold without Mr Buffett? Mr Abel, who currently runs Berkshire’s non-insurance activities, is not a stock-picker; he came up through the energy business.

That makes the defection in December of Todd Combs, one of Mr Buffett’s top investment lieutenants, to JPMorgan Chase, America’s biggest bank, a worry.

Berkshire’s record as an operator is patchier than its performance as an investor. Since being bought by Berkshire in 2010 BNSF’s profit margins have disappointed. In 2013 Berkshire teamed up with 3G Capital, a private-equity firm, to buy Heinz, a soup-maker, which it then merged with Kraft, a purveyor of processed cheeses. It has been a disaster, and in September Kraft-Heinz said it would split in two. Berkshire takes an uncontrolling approach to corporate control, and does not seek synergies across its portfolio.

Mr Abel’s talents as an investor will soon be put to the test. As interest rates come down, the cost of not putting Berkshire’s $US380 billion cash pile to work rises.

Berkshire could acquire another railroad (though BNSF has vocally opposed the ongoing tie-up between Union Pacific and Norfolk Southern). It could also bid for Chubb, another insurer in which it already has an 8 per cent stake. More likely are new investments in utilities or Japanese trading houses, Mr Abel’s areas of expertise.

Berkshire’s cash pile will also put it in good stead to snap up bargains if markets crash, as some fear they soon might. Even then, its powers would be diminished without Mr Buffett.

“What you’re going to lose is his Rolodex,” says Brian Meredith of UBS, an investment bank. Would Berkshire still be called upon to stabilise failing banks the way it was in 2008?

Mr Abel could instead start returning cash to shareholders. By its own rules, Berkshire’s current lofty valuation should preclude buybacks, and it has not paid a dividend since 1967. Doing so now would be another step towards becoming a more typical firm.

Berkshire recently appointed its first general counsel; more financial disclosure also seems likely under Mr Abel. Mr Buffett’s annual letters were blunt about Berkshire’s performance, and capitalism in general, but light on numbers.

Change will be slow, but certain. Loyal holders of Berkshire’s super-voting “class A” shares will give Mr Abel time to settle in, reckons Lawrence Cunningham of the University of Delaware.

Mr Buffett will remain chairman of Berkshire’s board, which is stacked with his family and friends. But rising institutional ownership of Berkshire’s “class B” shares—and the prospect of Mr Buffett’s stake converting to B shares after his corporeal departure—make a transition to more ordinary governance inevitable.

That would be a sensible end to an extraordinary career.

Originally published as As Warren Buffett retires, uncertainty looms for Berkshire Hathaway