THE ECONOMIST: China export boom masks weak consumer demand as deflation, tariffs, property crisis hit growth

THE ECONOMIST: China too complacent about the country’s dependence on trade growth.

When people in China talk about the “two meetings”, they mean the annual gatherings of the country’s legislature and its advisory body in March. But another pair of meetings this month could prove more important for China’s economy.

The Central Economic Work Conference, a yearly gathering of leaders, will set the direction for economic policy in 2026. (Not until the meeting is over will the outside world know exactly when it happened.)

Meanwhile, in a meeting on December 10, Vanke, once China’s second-biggest property developer, pleaded with its creditors for an extra year to repay a bond that will soon fall due.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.The Vanke meeting is another sign that China’s property slump, the source of much economic trouble, is far from over. But the conference in Beijing will probably confirm that China’s leaders have other things on their minds.

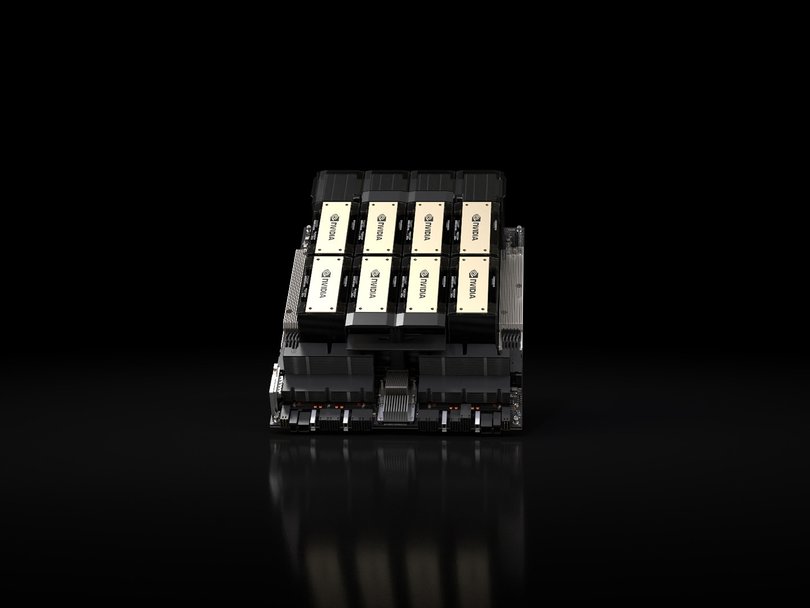

One of their preoccupations is technological self-reliance. By that yardstick, the past year has been a success. DeepSeek, an AI firm based in entrepreneurial Zhejiang province, has shown that China can compete with America’s best models despite constraints on its computing power.

And ten years after the launch of the “Made in China 2025” initiative, the country comfortably exceeded its goals for localising electric-vehicle-making and the renewable-energy industry.

Where China is not self-reliant it has also become more secure. It has turned its dominance in rare earths, critical elements used in high-energy magnets and other manufacturing components, into an effective economic weapon.

That will help it deter further Western attempts to cut it off from advanced semiconductors and other technological inputs it still cannot make itself. America’s government, for its part, now seems more inclined to loosen controls than tighten them.

On December 8, President Donald Trump said he would allow China to buy Nvidia’s H200 chips, not quite state-of-the-art but far more powerful than anything China has been sold before.

China’s “hard power” in economics, science and technology has “significantly improved”, boasted the Communist Party’s Politburo at a meeting on the same day.

China’s growing technological sophistication has also contributed to the surprising resilience of its exports. According to China’s customs administration, its trade surplus in goods in the first 11 months of the year exceeded $US1 trillion, more than the 12-month total for any previous year.

Such a bumper surplus seemed unlikely in the spring when Mr Trump raised tariffs on some Chinese goods to more than 145 per cent.

But even as China’s exports to America fell, its sales to the rest of the world more than made up the difference. Chinese firms found new markets to replace America. And they found new, more roundabout routes to reach America, circumventing the highest tariffs along the way.

As much as 70 per cent of China’s extra sales this year to the Association of South-East Asian Nations represent indirect exports from China to America via third countries, according to Goldman Sachs, a bank.

China’s surplus cannot, however, be chalked up only to the tenacity of its exporters. It also reflects the weakness of China’s own spending. Imports shrank in dollar terms in the first 11 months of this year, compared with a year earlier.

China’s investment spending is flagging, especially in construction, which tends to be import-intensive, points out Adam Wolfe of Absolute Strategy Research, a consultancy. Sales of new flats have fallen by half since their peak in 2021, even as exports have increased by a third. Falling home values have also dented the wealth of households, damaging their confidence and depressing their consumption.

The housing downturn over the past four years may have wiped out 100 trillion yuan ($21t) in property wealth, reckons Larry Hu of Macquarie, a bank. As a result, deflation has become entrenched. Figures released on December 10th showed that factory-gate prices fell year on year for the 38th month in a row.

Falling prices at home make Chinese goods more competitive abroad, points out Mr Wolfe. Deflationary pressure has also forced China’s central bank to keep interest rates lower than elsewhere in the world. That in turn has ensured that the yuan stays relatively cheap, giving China’s exports a further edge.

China’s exchange rate, adjusted for inflation and weighted to reflect China’s trade patterns, is 10 per cent below its average of the past ten years.

China’s export strength is then, in part, a product of the country’s domestic weakness. It is also, indirectly, a cause of it. Export momentum has helped China’s economy stay within reach of its official growth target of “around 5 per cent” this year, even without a more forceful fiscal stimulus or a more decisive effort to end the property slump. China’s leaders have not done whatever it takes to revive the property market, because they have not needed to, argues Mr Hu.

“Housing may not bottom out until policymakers can no longer rely on exports to drive growth,” he writes.

In the meantime policymakers have settled for more piecemeal measures. The Ministry of Finance has allowed local governments to sell more bonds and use the proceeds to buy land or unsold properties from developers. Zhengzhou, the capital of Henan province, has experimented with a scheme to purchase small flats from households who commit to buy pricier new homes instead.

But local-government finances are stretched. Only the central government has the fiscal firepower to carry out such schemes on the scale required.

Likewise, China’s attempts to lift consumer spending this year have been innovative but incremental. The government has expanded subsidies for households that are willing to trade in old cars, appliances or electronics for new ones.

They have rolled out childbirth subsidies, a year of free pre-school and vouchers to help the disabled elderly buy care. They have also subsidised consumer loans. But none of these initiatives has been big enough to turn sentiment around.

At its meeting on December 8, the Politburo cited the need for a “countercyclical” response to a slowing economy, points out Lu Ting of Nomura, a bank.

This phrase was missing from its comments in July. But the Politburo did not say, as it did last year, that the response should be “extraordinary”. Nor did it repeat last year’s commitment to stabilise the property market.

Doing so would be expensive, which is one reason why the central government will wait until it has no alternative. But allowing house prices to deteriorate and deflation to linger also has its costs. The more prices fall, the heavier debts weigh.

The longer deflation lasts, the harder it becomes to imagine an alternative. China could lapse into the “deflationary mindset” that haunted Japan for decades.

Nor can China count on exporting its way out of trouble for ever. Interest rates in the rest of the world are falling. The yuan is already facing pressure to rise.

Further European tariffs or an American tech bust would sap foreign demand. China would then have no choice but to stimulate domestic spending. But by then it might be even harder to revive it.

China’s leaders are keenly pursuing homegrown alternatives to foreign tech. But there are other measures of self-reliance.

According to the Politburo, domestic demand should be the “main driver” of the economy. But in the past year China has relied more on overseas spending to drive growth.

China’s leaders are wary of depending on foreigners to sell the country stuff. But they seem curiously content to depend on foreigners buying theirs.