THE ECONOMIST: Future of global trade hinges on America’s next president after Donald Trump’s tariff onslaught

The year is 2029 and Donald Trump has left the White House. Upon his successor’s shoulders rests the fate of the global trading system. The next president could end America’s one-sided tariff onslaught overnight, bringing down its effective trade-weighted tariff rate from the high teens to the 2 per cent or so it sat at before Mr Trump got going. Surely the choice is an obvious one?

From The Economist’s point of view, yes. Trade is mutually beneficial; taxes that stand in its way are self-harming. America’s tariff resurgence reflects the will of one man, not a popular uprising.

Just six months in, allies are already showing their unhappiness: India is shuffling closer to China; Europeans are shying away from buying American military equipment. Trade deals are paper-thin. And American manufacturing has lost jobs, puncturing hopes that import levies would lead to a rush of reshoring.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Yet such costs may not be obvious enough. Although markets sold off in cataclysmic fashion after Mr Trump’s “Liberation Day”, they are now hitting record highs: the S&P 500 index of big American firms is up by 12 per cent this year.

The broader economic damage has been masked, in part, by a boom in artificial-intelligence investment. This is a very different picture from the last great wave of protectionism.

In the 1930s the notorious Smoot-Hawley tariffs did not — in contrast to the oft-told history of the period — cause the Depression. They merely aggravated it. But that underlined the lesson that turning inward is foolish.

Facts on the ground may also stay a would-be liberaliser’s hand.

Firms that are unable to adapt to the new trading regime will go under; those that survive will often have spent a fortune relocating production, and be disinclined to do so again.

Some, shielded from foreign competition, will make a killing. For others, lobbyists will secure exemptions. In short, a new set of vested interests will be embedded throughout the American economy.

Moreover, tariffs raise revenues. The federal government earned $US30billions ($45.6b) from customs duties in August — more than three-quarters of which came from Mr Trump’s new levies. Lowering duties, therefore, would require Congress to find new “pay-fors” to make up the lost revenue.

Indeed, the loss of considerably less revenue, and a subsequent scramble to find alternative sources of cash, nearly held up congressional approval for tariff cuts as part of the Uruguay round of trade negotiations in 1994.

So what might lead to liberalisation? Paradoxically, it would probably have helped if today’s trade war were more warlike. Most countries have declined to fight America’s tariffs with tariffs of their own.

The EU drew up a list of goods to target, designed to inflict maximum political pain, but chose to delay imposing levies while it negotiated with America. A deal means that such tariffs have now been shelved.

Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, Brazil’s president, responded to America’s levies on Brazilian goods by pointing out that there are other markets keen to trade with his country. Even Canada’s prime minister, Mark Carney, who came to office on a wave of popular anger against America, is rowing back on retaliation. Only China has truly fought fire with fire.

In most senses, the absence of retaliation is a blessing. It has limited the short-term damage inflicted by Mr Trump’s tariffs. A hotter trade war, however, would have made the harm from protectionism more obvious.

The pain that Americans will feel from higher prices and slower economic growth, relative to a world of free trade, is real and will mount the longer tariffs remain in place, but it is not as obvious as shuttered factories and howls of outrage from politicians with constituents suffering from the loss of international custom. A grinding diminution of competitiveness is ultimately easier to ignore than an acute crisis.

Retaliation would also provide countries with something to offer Mr Trump’s successor. As Douglas Irwin of Dartmouth College points out, America has typically liberalised its trading terms only when it feels aggrieved.

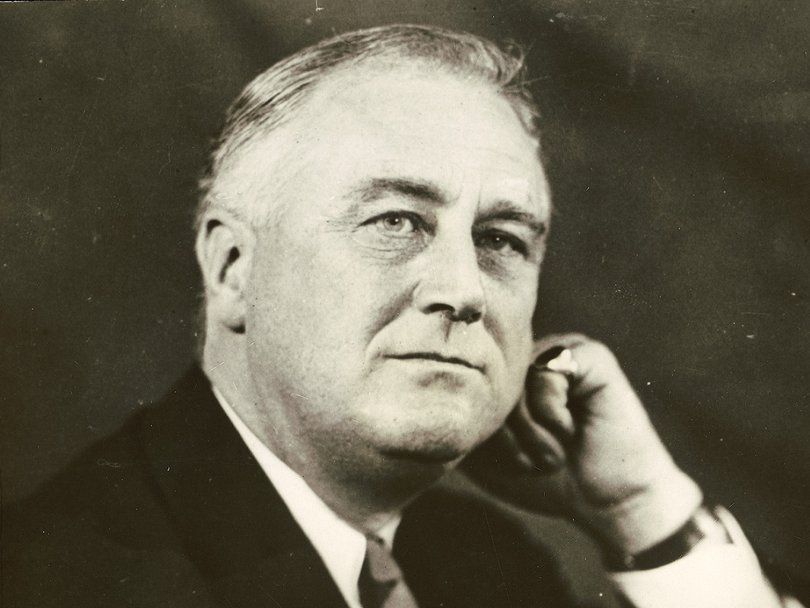

On these occasions, it lowers its own tariffs in exchange for larger concessions from its trade partners—an approach that has long had a basis in legislation. Congress gave Franklin Delano Roosevelt, president during the Depression, the power to lower America’s tariff rate by up to 50 per cent using the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act, but restricted it to when other countries cut their levies at the same time.

Presidents have typically taken advantage of this (and similar) powers only when there has been a widespread belief that America is missing out. The so-called Kennedy round of trade liberalisation in the 1960s, for instance, was sparked by a sense that America was being excluded from the benefits of Europe’s newly formed common market.

Not their bill to foot

This time round, America’s trading partners have judged that tit-for-tat responses would lead to escalation and self-harm. Why should they take the pain of retaliation in an attempt to make Americans see sense?

The deterioration in global trading conditions is an American problem. It is Mr Trump who has ramped up tariffs, and border taxes are largely paid by domestic consumers. On top of this, the country’s politicians have the capacity to end the conflict.

Mr Trump is making use of powers that he argues Congress has delegated to the White House. The Supreme Court may soon decide that he is wrong. In November, it will hear arguments over the legal basis for many of his border taxes — the citation of two national emergencies under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act.

However, a defeat would not be the end of Mr Trump’s crusade. His lawyers would root around in the statute books in order to find other grounds for his levies.

Americans, then, have the solution within their grasp: simply vote for a free-trading president in 2028, even if tariffs cause only a gradual decline, rather than outright catastrophe.

Originally published as Would an all-out trade war be better?