THE ECONOMIST: Manufacturing’s ‘ChatGPT moment’ has arrived as AI transforms the factory of the future

THE ECONOMIST: Artificial intelligence promises to transform how and where things are made.

“Do you know what really impresses me? I saw a robot pick up an egg!’’ exclaimed Roger Smith, chairman of General Motors, in 1985. The American carmaker, which two decades earlier had been the first company to install a robotic arm, was then in the process of creating a “factory of the future” in Saginaw, Michigan.

Smith envisioned a “lights-out” operation — no humans, only machines — that could help his company keep up with Japanese rivals. The result was shambolic. Witless robots couldn’t tell car models apart, and were unable to put bumpers on or paint properly. Costs ran wildly over budget. GM eventually shut down the factory.

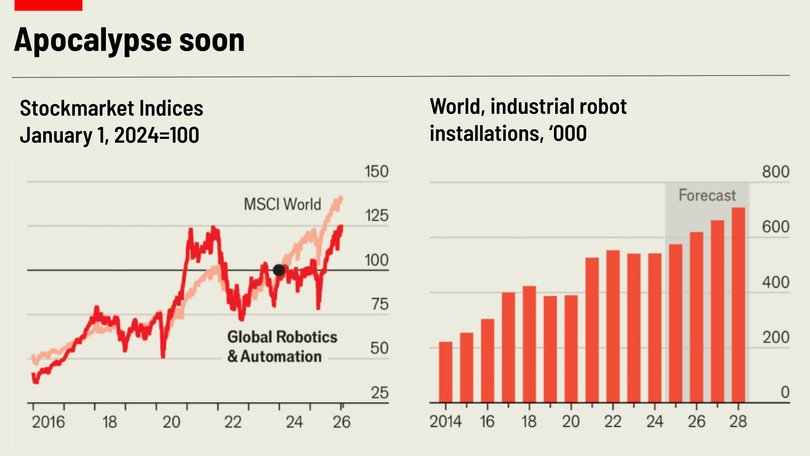

Automation has come a long way since then. Yet Smith’s vision remains far ahead of reality at most factories. According to the International Federation of Robotics (IFR), an industry association, there were around 4.7 million industrial robots operational worldwide as of 2024 — just 177 for every 10,000 manufacturing workers. Having risen through the 2010s, annual installations surged amid the pandemic-era automation frenzy, but flattened off afterwards, with 542,000 installed in 2024.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.That has been mirrored in the wider market for factory-automation equipment, including sensors, actuators and controllers, which has faced tepid demand over the past few years amid a slowdown in manufacturing, particularly in Europe. Despite a stellar performance during the pandemic, shares in the industry’s big suppliers have lagged behind those of other rich-world companies since the beginning of 2024 (see chart below, left).

Yet analysts see 2026 as an inflection point. The IFR reckons that annual robot installations will increase to 619,000 this year (see chart, above right). Roland Berger, a consultancy, forecasts that inflation-adjusted growth in sales of industrial-automation equipment as a whole will rise from a meagre 1-2 per cent in 2025 to 3-4 per cent in 2026, then notch up 6-7 per cent for the remainder of the decade.

Partly that reflects tailwinds brought by the reduction of interest rates in the West over the past 18 months. But it is also a product of deeper structural forces. Western policymakers have turned to subsidies and tariffs to encourage manufacturing back to their shores; factory construction soared during Joe Biden’s time in office. With populations ageing, many manufacturers are struggling to find enough skilled operators to man their assembly lines, leading to rising demand for machines.

What is more, advances in industrial software are helping overcome many of the challenges that have previously hindered efforts to automate production.

Silicon Valley is abuzz with discussion of how the latest wave of generative artificial intelligence can be used not just to power whizzy chatbots, but also to transform manufacturing.

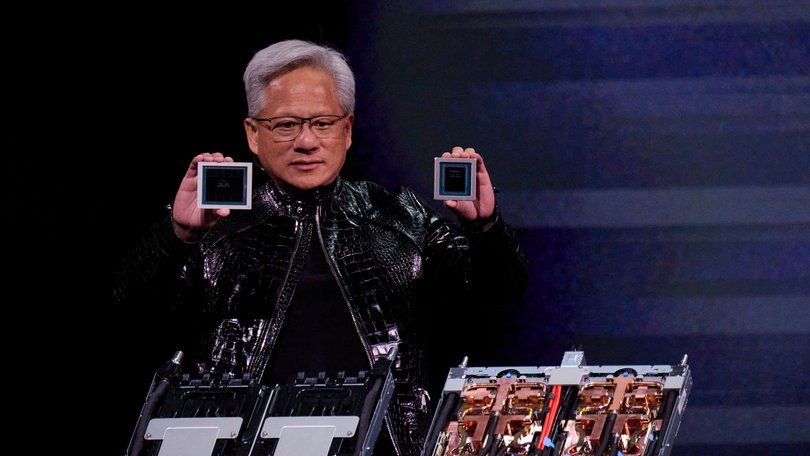

“The ChatGPT moment for robotics is here,” declared Jensen Huang, boss of Nvidia, a chipmaker and darling of the AI boom, on January 5. In time, the result may be factories that are not only more mechanised, but nimbler and smaller.

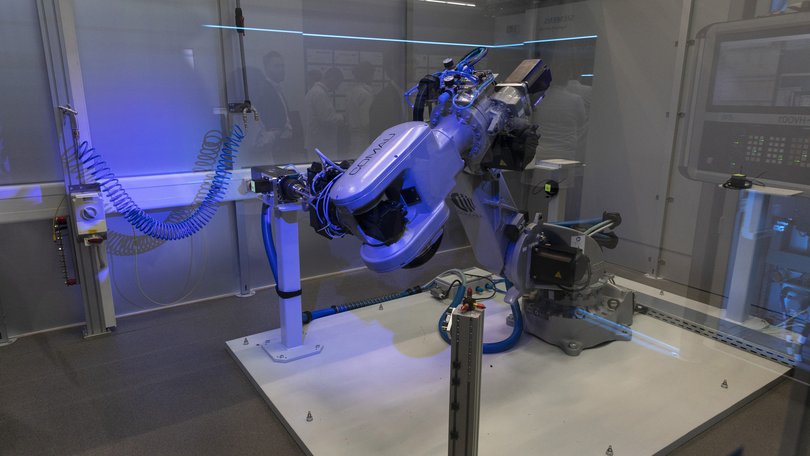

Hints of the future can already be glimpsed at the Bavarian factories of Siemens, itself a maker of automation equipment, in Amberg and Erlangen (above). The Amberg factory, which makes 1500 variants of machine controllers, today produces around 20 times what it did when it opened in 1989, but with approximately the same number of workers.

Robotic arms, many of them made by Universal Robots, whose parent company is Teradyne, an American business, do much more than pick up eggs. In glass enclosures they move swiftly about, welding, cutting, assembling and inspecting. Workers monitor and control production from computers attached to the machines.

The factory in Erlangen, which produces electronic components, is equally futuristic.

Autonomous trolleys with screens attached zoom around the shop floor transporting goods between stations at which humans work side-by-side with robots. Others have lined themselves up neatly to charge.

Factory hardware has come a long way in the past few decades. Robotic arms that once moved along three axes — up and down, left to right, front to back — typically now move along six. Sensors and cameras guide their motion. A single robot is often able to perform several manufacturing steps. They have also plunged in price as production has scaled up and Chinese suppliers have entered the business.

Even bigger advances are taking place in the software that makes machines and factories hum.

Robots were once rigidly designed for one activity. That required manufacturers to be “stuck in a moment of time” in order to capture the benefits of automation, notes Ben Armstrong of the MIT Industrial Performance Centre.

Now the machines can be reprogrammed for another job with a tweak to their code. For example, robots that were previously used by Foxconn, a Taiwanese manufacturer, to put the circular “home” button on earlier generations of iPhones were repurposed to install microchips. Such flexibility has further improved the lifetime return on investment from robots.

Software is changing manufacturing in other ways, too. Computerised simulations known as “digital twins” are making it quicker and cheaper to test product designs and manufacturing processes; two-dimensional, paper-based blueprints have been replaced by precise, three-dimensional reproductions. Suppliers of automation gear have piled in.

Last year Siemens bought Altair, an industrial-software firm, for $US10 billion ($15b), its largest acquisition ever. Software, which typically generates a higher margin than hardware, now accounts for a third of sales in the conglomerate’s industrial-automation division.

Generative AI promises to take this transformation a step further. Until recently, precisely modelling the actions of a robot was often impossible owing to the many variables involved, a problem known as the “sim-to-real gap”. Simulations tended to break the moment lighting or the shape of an object changed.

Supersized AI models, trained on vast amounts of data from sensors and cameras, may help solve that.

As simulations become more accurate and detailed, it may be possible to program robots to approach a physical task much as a human would, perceiving, understanding and then reacting to the situation. The prospect of harnessing “physical AI” to revolutionise manufacturing has generated much excitement.

During the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas this week Nvidia unveiled a suite of chips and freely available AI models designed specifically for robots.

In October SoftBank, a Japanese conglomerate with big AI ambitions, announced it would acquire the robotics division of ABB, a Swiss industrial giant. Startups from Silicon Valley to Shanghai are building humanoid robots that they hope will one day replace factory workers. So is Elon Musk.

The automation industry’s incumbents are also investing heavily in physical AI.

Peter Koerte, Siemens’s chief technologist, reckons that AI will become the “brains” of factories much as machines have become their “muscles” (albeit with human oversight). In September his firm announced a deal with German machine-makers to pool anonymised data from their hardware and build AI models for industrial use.

On January 6, it said that it would expand its partnership with Nvidia and develop, among other things, an AI-powered tool for building digital twins. Last year Hitachi, a Japanese industrial giant that is also working with Nvidia, unveiled a new AI-powered software platform that ingests and analyses data from the many sensors and cameras across a factory and can alter operations in response.

Some now talk of factories becoming not just automated, but autonomous. In November, Tessa Myers of Rockwell Automation gushed:

Imagine a factory where machines anticipate needs before they arise, where material moves seamlessly without human intervention and production lines adjust in real time to changes in demand or disruptions.

The American machine-maker is piloting the idea at a small facility in Singapore.

The result of all this may be a very different type of factory. With each robot able to perform a wide array of tasks, shop floors may no longer need to be designed around lengthy assembly lines. Combine that with falling hardware costs and many firms may soon find it viable to spread their manufacturing across a network of smaller plants.

For years the trend has been towards larger sites, fashionably referred to as “gigafactories”, as manufacturers have sought economies of scale. But smaller factories would have plenty of advantages. They could be built closer to urban centres, making it easier to bring in the workers who, at least for the time being, will remain both essential and difficult to find.

Proximity to customers would also be useful, particularly given the persistence of tariffs. And a more dispersed manufacturing footprint would reduce the risk that a failure at a single factory becomes a crisis.

The factory of the future will look very different from what Smith imagined — and may be even more transformational.

Originally published as The “ChatGPT moment” has arrived for manufacturing