THE ECONOMIST: Silicon Valley is racing to build the first $1trn unicorn

THE ECONOMIST: Flush with cash and fired up by the AI boom, many venture capitalists are looking to hold on to the most promising startups for longer, hoping to ride their valuations into the stratosphere.

Two years ago, when Nvidia first joined the club of trillion-dollar firms, plenty of investors worried that its shares were beginning to look pricey.

Yet those who happened to buy a slice of the artificial-intelligence (AI) chipmaker at the time would since have quadrupled their money.

On July 9 Nvidia became the first ever company to reach a market value of $US4 trillion ($AUD6t).

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.The sizzling returns enjoyed by investors in publicly traded tech giants over the past few years has been the cause of much envy among Silicon Valley’s venture capitalists (VCs).

It is not just Nvidia. CoreWeave, a cloud-computing provider, has seen its market value rise by over 300 per cent since it listed in March.

Flush with cash and fired up by the AI boom, many VCs are now looking to hold on to the most promising startups for longer, hoping to ride their valuations into the stratosphere.

Some now say it is a case of when, not if, Silicon Valley creates its first unlisted firm worth $1t.

The pursuit of that goal is transforming how the VC industry operates — and making a volatile business riskier still.

As recently as 2023 the VC industry was in a funk.

Fully 344 unicorns — unlisted firms worth more than $1 billion — were minted in America in 2021 amid the pandemic-era funding bonanza.

Two years later the figure was just 45, as higher interest rates brought the VC industry crashing down to earth.

Many of the valuations set amid the boom became as illusory as the mythical beasts for which they were named.

So-called zombie unicorns from that period, whose valuations would now be far lower if VC firms were to correct them, still haunt the Silicon Valley landscape.

Yet generative AI has sent Silicon Valley into a new frenzy that is beginning to look even more berserk than the last.

According to PitchBook, a data gatherer, almost two-thirds of VC dollars invested in America in the first half of this year went to AI firms.

Unicorns have given way to decacorns (worth more than $10b) and hectocorns ($100b-plus).

OpenAI, maker of ChatGPT, was most recently valued at $300b.

Coatue, an investment-management firm, has calculated that there are currently more than $1.3t-worth of private companies valued at $50b or higher, greater than double the level two years ago.

These rich valuations are partly the result of an abundance of capital.

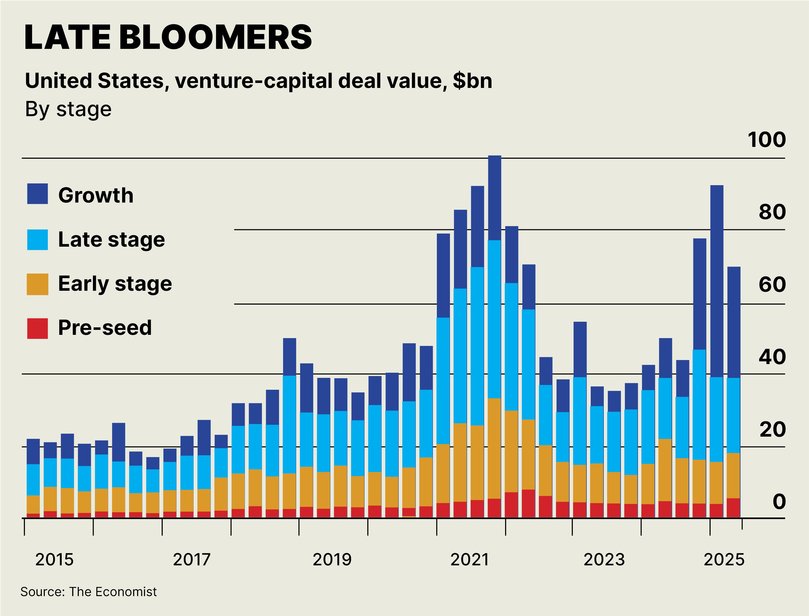

Last year assets managed by American VC firms approached $1.3t, more than three times the level in 2015.

Money left over from the pandemic-era fundraising boom has been swiftly diverted to AI startups.

New foreign investors eager to splurge on AI, such as Middle Eastern sovereign-wealth funds, have been handing fistfuls of cash to VCs, making up for the retreat of some pension funds and endowments.

VCs have also been allocating a much greater share of their expanding cash pile to mature startups, rather than fledgling ones.

In the first half of 2025 these accounted for 78 per cent of the value of VC deals, up from 59 per cent in the same period a year before.

In a sign of the times, SoftBank, a Japanese tech investor, is throwing sums around that are wild even by its profligate standards.

Masayoshi Son, SoftBank’s boss, has said it will put $32b into OpenAI by the end of the year — more than any initial public offering has ever raised.

The fact that startups are staying private for longer partly reflects the preferences of founders who would rather avoid the drudgery — and scrutiny — that comes with being listed on public markets.

But whereas VCs once used to press them to list, today they are in no hurry, and are eager to capture more of the growth in valuations as companies scale up.

The trouble with pushing out investment horizons is the need for liquidity.

Traditionally, VC firms have had to exit their holdings after a few years in order to return the proceeds to those whose money they are investing.

Even before the latest bonanza, Silicon Valley’s financiers had begun to experiment with changes to their investing model to enable them to keep hold of startups for longer.

These efforts are being turbocharged.

One workaround is secondary tender offers, which allow early VC backers and employees paid in equity to sell their shares without having to wait for a public listing or another private funding round.

According to PitchBook, there were some $60b-worth of such transactions in the first quarter of 2025, up from $50b in the final quarter of last year.

Still, that level of liquidity is a far cry from what is available in public markets.

Over the past month an average of $26b-worth of Nvidia shares have traded hands each day.

Another solution is permanent capital.

Sequoia Capital, a VC stalwart, declared the traditional 10-year fund “obsolete” in 2021, and has since replaced it with a permanent structure, the Sequoia Capital Fund, which combines investments in unlisted startups with liquid stakes in public companies it has previously backed.

Other VCs, such as Lightspeed Venture Partners, have recently turned to continuation funds, which bring in fresh capital to allow them to hold on to startups.

All this is changing the character of the VC industry.

The largest firms, such as Andreessen Horowitz, Sequoia Capital, Lightspeed and General Catalyst, have ballooned in size.

They now deploy tens of billions of dollars across numerous funds, with scores of people hunting deals.

At the same time, a small cohort of youngish firms, such as Thrive Capital, led by Josh Kushner, and Greenoaks, led by Neil Mehta, are competing with a different approach.

They are raising sizeable funds of their own, but are using them to back a select few companies, with small investment teams writing big cheques to rival those of the VC giants.

Vince Hankes of Thrive, which has invested more than $1b in OpenAI, believes that even within the firm’s relatively small portfolio of companies, there could be more than one startup that in time will be worth $1t.

His firm is also experimenting with a private-equity-like model of acquiring and combining existing companies in industries such as IT services and infusing them with AI.

The transformation of the VC industry brings risks.

Writing ever bigger cheques for companies that have yet to prove they can turn a profit, and holding on to them in the hope that they eventually will, raises the likelihood of enormous losses.

The stratospheric valuations enjoyed by the current generation of buzzy startups could turn out to be as overinflated as today’s zombie unicorns were a few years ago.

A venture drought could follow. Yet the prospect of trillion-dollar rewards makes it hard to keep the pocketbook closed.

Originally published as Silicon Valley is racing to build the first $1trn unicorn