THE ECONOMIST: The autocrat’s guide to financial growth and why it isn’t working for some rulers

THE ECONOMIST: Why today’s authoritarian economies are struggling to match their ambitions.

Muhammad bin Salman is one of the world’s most secure autocrats. He has no need to pay off rivals or buy elections. Yet by 2030 his government will have spent almost $US3 trillion ($4.62) on Vision 2030, plan to transform Saudi Arabia’s economy. Officials are backing man-made islands, luxury hotels and EV factories. They will take anything that has the smallest chance of creating economic growth, even if it is in decades, says a megaproject executive, even fantasies and failures.

MBS is one of several autocrats fixated on economic growth. Gulf monarchs, East African leaders, strongmen in (just about) democratic countries — all are inspired by China and Singapore, which managed to combine authoritarian rule with economic success. Many are willing to adopt orthodox policy.

They see growth as a source of legitimacy, seeking to enrich their populations, rather than just elites. As such, they employ skilled technocrats to set policy, try to lure investors with promises of stability and engage in lavish industrial policy. And yet, despite all this, they are increasingly struggling to deliver growth.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.China and Singapore are an inspiration for a reason — they stand out. Autocrats have tended to pursue growth haphazardly at best. Kevin Grier of Texas Tech University and Michael Munger of Duke University have found that, from 1950 to 2006, those who managed a decade or more in power produced growth of one per cent a year, a measly amount.

The worst treated policy as a means of personal enrichment. More often the likes of Suharto in Indonesia and Myanmar’s junta ran the economy in such a manner as to placate elites, apportioning profits to allies while repressing citizens.

The new breed of rulers was first identified in 2015 by Hilary Matfess of the Council on Foreign Relations, a think-tank. She termed them developmental authoritarians. Paul Kagame has courted investors by opening Rwanda’s capital account, promising subsidies and sending roadshows across the world.

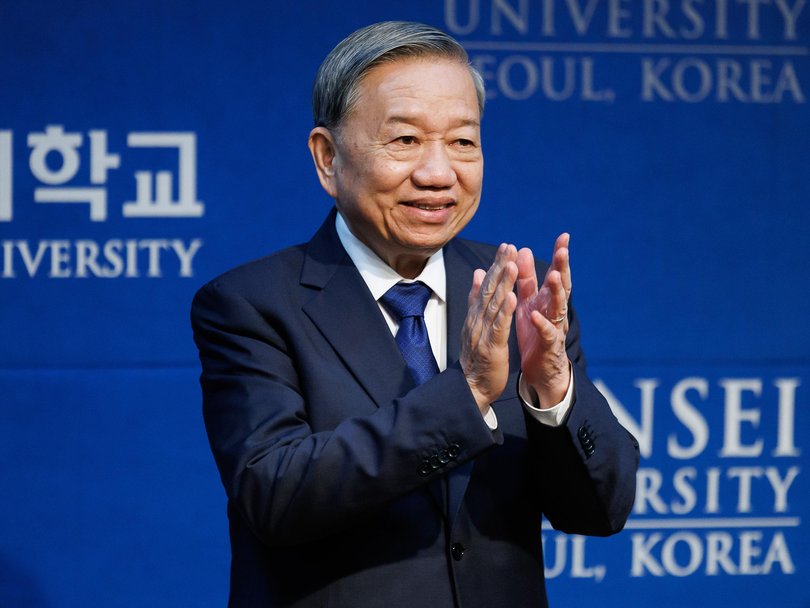

In Ethiopia Abiy Ahmed, who came to power after Ms Matfess’s paper, has scrapped capital controls and floated the birr. In the Gulf ruling families are trying to reduce their dependence on oil. Vietnam may already be South-East Asia’s fastest-growing economy, but To Lam, its new ruler, wants to up the pace.

After all, under Park Chung-hee’s authoritarian rule, which ran from 1963 to 1979, the average South Korean’s income went from that of a sub-Saharan African to that of an eastern European. And whereas South Korea became a democracy, Deng Xiaoping in China showed that there was nothing inevitable about such a transition. Instead, he oversaw strong economic growth and cemented his party’s rule while doing so. Today everyone from Mr Kagame to Indermit Gill, the World Bank’s chief economist, professes admiration for China’s and Singapore’s achievements.

The change of approach reflected demographic trends. In the 2000s economists talked of authoritarian bargains, in which despots compensated for the general unpleasantness of life without political rights with handouts. Today populations are too large and too young for such deals. The Gulf is racing against the depletion of oil funds; Ethiopia’s population is forecast to grow by 90m from 2020 to 2050.

From the Kennedy School to Kuwait

Melding pro-growth policy to an authoritarian political economy means ceding control. The Rwandan government has provided venture capital for everything from milk production to peat mining. It then sells stakes in successful ventures to private investors (part of a telecommunications firm recently went to T-Mobile, an American giant, for instance).

One of Mr Lam’s first policies in Vietnam was to exempt small businesses from corporate tax. Two years ago, for those putting more than $50m into the country, Bahrain got rid of almost all the paperwork foreign investors usually require. MBS’s latest reforms, introduced in February, seek to bring employment practices into line with America.

Well-run, relatively efficient state-owned conglomerates also attract foreign investors. They crave stability and a young, popular autocrat is less likely to rip up commitments than a cast of leaders in a democracy. Why, ask state-sponsored salespeople who tour investment conferences, take the risk? Abiy is 48 and MBS is 39; they make plans in decades. Alongside Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 (published in 2016), there is Bahrain’s Vision 2030 (published in 2008) and Ethiopia’s Growth and Transformation Plan (lasting until 2030).

Despite the alluring pitch, in recent years flaws have emerged. Foreign businesspeople complain of micromanagement. State-owned firms crowd out private ventures: so ambitious are the government’s plans, Saudi Arabia suffers from a shortage of construction materials; the IMF has warned Ethiopia its banks are too busy lending to the state to support local businesses.

In some places, when goals are not met, officials may fiddle the figures to avoid reprisals. Indeed, an IMF official suggests that the true Rwandan GDP growth rate is a couple of percentage points below the official one. Ethiopia appears to be overstating its wheat production.

Although many of the plans are long-term, they have been in place for long enough to start to make judgments. We have picked four measures: foreign investment and economic growth reflect core ambitions; GDP per person and health spending, the extent to which benefits are trickling down.

Most regimes are failing to meet their own lofty goals. In 2000 Mr Kagame said he wanted Rwanda to be a middle-income country by 2020 — a target he is still to meet. Non-oil portions of Gulf economies are growing more slowly than the upper-middle-income average. Since 2015 the average income of someone under a growth-fixated autocrat has risen by 14 per cent, against 23 per cent in comparable countries.

This is not to say that growth is meagre everywhere. Ethiopia’s economy grew by over 7 per cent last year, four percentage points above the African average. Rwanda managed a similar pace, according to official figures. Saudi Arabia was thought to be among the most sluggish. But on August 4 the IMF revised its calculations, looking at more industries. Its non-oil growth estimate for 2023 rose from 3.8 per cent to 5.8 per cent.

In many cases, though, growth relies on state spending. The Public Investment Fund, Saudi Arabia’s wealth fund, is responsible for a tenth of non-oil GDP. Last year over half Rwanda’s investment came from state-owned firms.

Foreign private-sector cash would indicate a true capitalist boom. Last year Saudi Arabia received less than the average country in the region as a share of GDP; Bahrain, less than Nicaragua. Trade balances have hardly improved. Saudi Arabia imports three times more non-oil goods and services than it exports.

All told, growth has not been sufficient to satisfy ballooning populations, nor to boost tax revenues. In 2023 Saudi Arabia collected less tax, as a share of GDP, than an average low-income country. Fiscal pressure is building and IMF economists reckon the country’s non-oil growth will stay below 3.5 per cent for the next two years.

Rwanda’s debts will force Mr Kagame to cut back. Although technocratic policy has delivered better outcomes, and some measure of popularity, leaders may soon face a choice: properly liberalise, turn to even nastier methods of securing acquiescence or try to buy popularity with handouts in tighter times. How deep does their commitment to economic change run?

Originally published as Growth-loving authoritarians are failing on their own terms