THE ECONOMIST: The curse of Labubu, Ozempic and ChatGPT — challenges facing Pop Mart, Novo Nordisk and OpenAI

THE ECONOMIST: Blockbuster products brought overnight success — and unexpected problems.

Every chief executive dreams of it: a product so successful that it propels their company from obscurity to superstardom seemingly overnight.

Among the lessons from 2025, however, is that runaway success is not all upside. As the experience of whizzy chatbots, weight-loss jabs and wacky dolls illustrates, it brings problems, too.

The first pitfall is that bosses face the vexed task of scaling up their business to satisfy a level of demand that is impossible to predict.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Consider OpenAI, maker of ChatGPT, a product so successful it has precipitated an investment frenzy not seen for a generation. According to OpenAI, around a tenth of the world’s population now uses its chatbot.

The firm reckons that its yearly revenue will reach roughly $US200 billion by 2030 ($298b) ten times its current annualised rate. In response, it has committed to $US1.4 trillion of spending on computing power over the coming years, including through a series of circular deals funded by the recipients of its largesse.

Growth of the sort that OpenAI is projecting has not been seen before. If it falls short, the firm will probably go broke, bringing the artificial-intelligence boom to a grinding halt.

Yet underinvestment also brings problems beyond the failure to take full advantage of surging demand. A particular danger is the rise of shadow markets — the second pitfall of overnight success — which can cause lasting trouble for businesses.

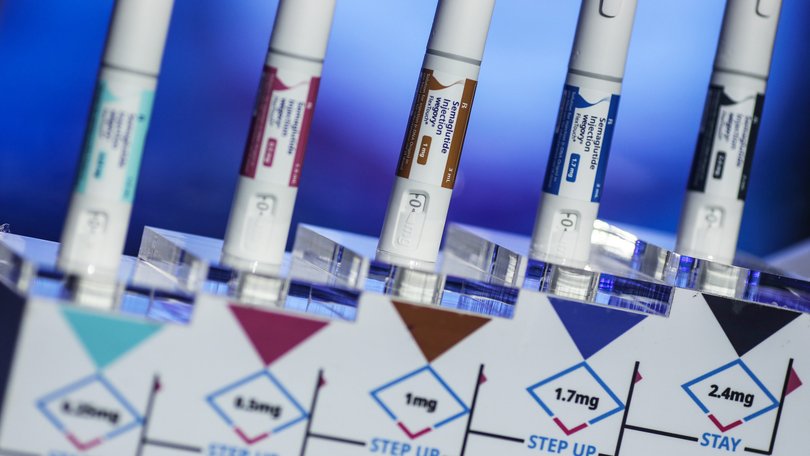

Take Novo Nordisk, the Danish pioneer of semaglutide weight-loss jabs Ozempic and Wegovy. Because it was slow to ramp up its manufacturing capacity, “compounding” pharmacies, which in America are permitted to offer replicas of drugs that are in shortage, were able to muscle in.

Although the shortage ended in February, around one million Americans still take the copycats — which are cheaper but, according to Novo, less safe — as compounders have used loopholes to keep producing them.

Pop Mart, the Chinese firm behind the mischievously grinning, nine-toothed Labubu dolls that shoppers have queued up to buy this year, has faced similar trouble. Although it has increased production, it is battling a scourge of fake eight- or ten-toothed Lafufus that have flooded online marketplaces.

The final pitfall of overnight success is that it attracts legitimate competitors who can learn from both your triumphs and disasters.

Call it the first-mover disadvantage. Eli Lilly, which brought its own weight-loss jab, Zepbound, to Americans two years after Novo, has this year pulled ahead of its Danish rival in the market for obesity drugs. That is partly because Zepbound is more effective.

But Lilly also learned from Novo that it needed to have ample supply in place and offer its treatment directly to consumers, many of whom would rather not have to visit the doctor for a prescription, and are not covered for one by their insurers.

Similarly, OpenAI’s success inspired competitors that were able to learn from its breakthroughs before it had time to entrench itself with customers. The first shock came in January, when DeepSeek, a Chinese AI lab, launched a cutting-edge model it had developed on a shoestring, which it made freely available.

More recently, OpenAI has been threatened by Google, which was mobilised into action by the success of ChatGPT and last month launched a model that is neck and neck with OpenAI’s best.

With its vertically integrated business model, deep pockets and established distribution channels — including nearly 4 billion Android users worldwide — Google now looks like the AI company to beat.

The wider lesson from all this is that hit products rarely lead to enduring commercial success. Instead, consider two of 2025’s quiet achievers.

Walmart, America’s mightiest retailer, has seen its market value soar to nearly $US1 trillion without fanfare. Its enormous scale, which it uses to push down costs and pass the savings on to customers, has won over many stretched shoppers this year.

Plenty of them will also have been struck by the retailer’s digital reinvention. Look, too, at CATL, China’s battery colossus, whose secondary listing in Hong Kong in May was the largest share offering worldwide in 2025. Its hefty investment in research and development has given it a commanding lead. It is using that strength to expand into batteries for the grid.

Life after the one-hit wonder

Bosses should take heed. A hit product can bring a company to the attention of millions. But lasting success comes from a business model that is difficult to replicate, and which keeps evolving in a fast-changing world.

Originally published as What Novo Nordisk, OpenAI and Pop Mart have in common