THE ECONOMIST: Why America’s strengthening dollar under Trump is set to rattle the rest of the world

Donald Trump’s policies could set the greenback soaring, which spells trouble for growth in the rest of the world.

In 1971 John Connally, then-the American treasury secretary, told his European counterparts the dollar was “our currency, but your problem”.

Over the following half-century the global economy has transformed, but Connally’s adage still rings true: even though the value of the dollar remains largely set by domestic developments in America, its swings almost always send ripples across the world. One such big swing may be on the cards, as the economic policies promised by Donald Trump, America’s president-elect, look set to turbocharge the greenback.

That spells trouble for growth in the rest of the world.

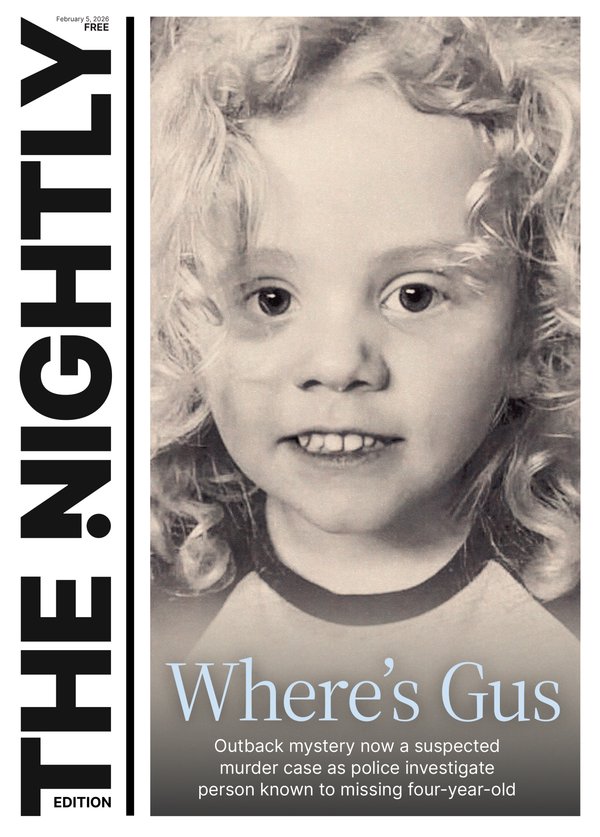

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Exactly what parts of his economic agenda Mr Trump will want — and be able — to implement is not yet clear. But the giddiness in America’s stockmarkets gives clues as to what investors expect (the S&P 500, an index of large American firms, hit successive records on November 6, 7 and 8).

Traders reckon the incoming administration will boost profits at American firms through tax cuts and deregulation, as Government borrowing soars. A combination of higher deficits and rekindled inflation, in turn, may force the country’s central bank to keep interest rates higher than it would have without Mr Trump in power. Those higher rates would make holding dollar securities more attractive, providing a tailwind to the greenback.

Part of this scenario is already playing out. On November 7 the Federal Reserve, as expected, cut its benchmark interest rate by a quarter of a percentage point, lowering its target range to 4.5-4.75 per cent. But Jerome Powell, its chairman, left open the possibility the Fed would hold rates steady at its December meeting, rather than continue to slash them.

Tellingly, a statement by the rate-setting committee accompanying its decision no longer said it had “greater confidence that inflation is moving sustainably toward 2 per cent” , as it had in its previous statement in September. The prospect of higher American interest rates has pushed the value of the dollar up by 1.5 per cent against a broad basket of currencies over the past four weeks.

A rising dollar often comes hand in hand with a weakening global economic outlook.

One reason for this is that during times of economic turmoil, investors tend to sell off their risky assets and pile into ones they perceive as safe, notably the dollar and American Treasuries.

Whereas a worsening outlook tends to boost the dollar, a rising dollar often worsens the outlook, too. IMF research published in 2023 found after one year, a 10 per cent rise in the value of the dollar decreases output in emerging economies by 1.9 percentage points.

Rich countries are less affected, but still see their output cut by 0.6 percentage points. Relief is slow to come: according to the paper, the deleterious effects of a mighty dollar tend to linger for 2½ years for emerging economies, and for a year for rich countries.

Swings in the dollar’s value rock the global economy via two main channels: trade and finance. More than 40 per cent of global trade — most of it not involving America — is invoiced in dollars.

A stronger greenback raises the costs for importers, which dampens demand for goods from abroad and reduces overall trade volumes. Across much of Asia and Latin America, therefore, movements in the dollar’s value matter more than how local currencies behave. One academic study, published in 2020, found that a 1 per cent rise in the value of the dollar against all currencies predicts a 0.6 per cent decline in trade between countries in the rest of the world, after controlling for other factors. According to the Bank for International Settlements, a club of central banks, a stronger dollar also raises costs for buyers of intermediary goods, creating a risk that long supply chains collapse.

Just as important as the trade effects of a rising American currency is the financial feedback. For countries and firms that have borrowed in dollars but lack sources of dollar revenue, a rising greenback mechanically bloats their debt burden and boosts their interest costs.

Higher interest rates in America, coupled with a rising dollar, also makes investing in the rest of the world less attractive. Capital tends to flow out from emerging markets, forcing them to raise interest rates as well, tightening monetary conditions just when their economies may start to suffer from a general trade slowdown.

This magnetic pull on borrowing costs outside America is already evident. In the early hours of November 6, when the election result became clear, the yield on American Treasuries rose sharply. So too did the yields of Australian, New Zealand and Japanese government bonds.

Some of these rises have since been reversed in response to the Fed’s cut, but the respite may prove only temporary. Any rebound in yields would be badly timed: many central banks are trying to prop up soggy growth at home by lowering policy rates and facilitating credit.

Whether a strong dollar lasts remains to be seen. Donald Trump himself has long bemoaned that a mighty greenback hurts domestic manufacturers and costs American jobs. But he cannot easily force the central bank to cut rates.

And as long as rates stay high, America’s currency will remain the refuge of choice for investors — and a thorny problem for the world.