Andrew Tate, Joe Rogan & other incels: How social media influencers rein men in with cult leader tactics

First they tell you your problems are not your fault. Then, they show you how you can be special and better than everyone else.

First they appeal to you with a message you have been waiting for.

“Your problems aren’t your fault, there is someone to blame for all of this.”

“I know how to make all your troubles go away.”

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.This hook is nothing new, but it’s causing havoc online in the hands of narcissistic and power hungry social media influencers as they spread harmful ideology to build their own following and feed their own desire to manipulate.

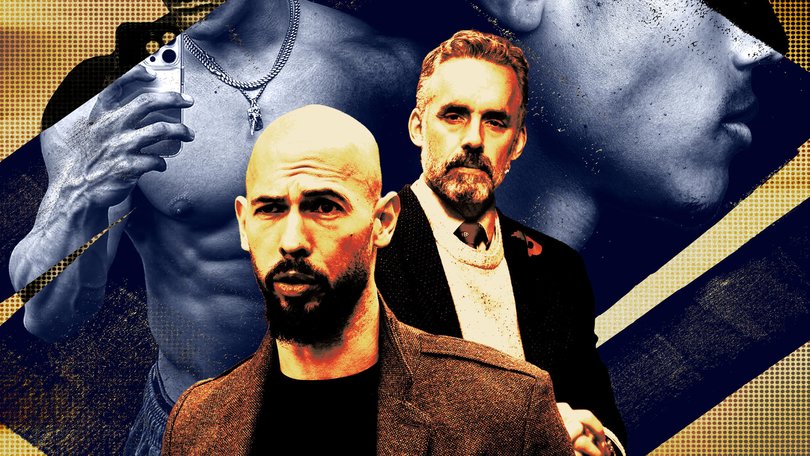

The big names, Andrew Tate, Joe Rogan and Jordan Peterson are recognised as the golden trio of the manosphere, an online community built around a common enemy — women.

We throw their names around, but they have young audiences lapping up misogynistic messages while lining their pockets.

We’ve heard of rabbit holes and echo chambers, but these influencers are modelling their manipulation off something much older.

They’ve been studying cult leadership.

It’s not your fault, it’s her fault

We are fascinated by cults, by the hive mind and the breaking down of individuality.

In her book Cultish, Amanda Montell said language is at the heart of how we exercise cultlike influence. From conspiracy theorists to exercise class instructors, the art of exclusivity is widely practiced.

Brands will create their own terminology, or use social media to create in-jokes that encourage their customers to assign their company with an identity, and see themselves as a valid, in the know, by-product.

But according to forensic psychologist Genevieve Willis, it takes a certain type of person to prey on insecurities to build a platform based on hate.

“Once a narcissistic personality develops, there’s a combination of wanting power, wanting to feel superior, wanting to feel important. Being able to influence other people just feeds into that sense of ‘how good I am’,” Ms Willis said.

She likened the techniques used by toxic influencers to those used by groomers.

“They have to develop a connection with people and be tapping into insecurities, which is part of that sort of rapport building, or grooming process of making people feel understood and important,” she said.

Ms Willis said audiences are first drawn in with the promise of something which seems worthwhile.

“They’re using legitimate topics to draw people in. The manosphere talks about male dominated sports, health, finances, how to get rich,” she said.

“These things are valuable to young people, it kind of initially gets them in. But then, toxic messages are layered into those topics.”

From here, influencers tap into the old “us vs them” cult tactic to unite their audience against a common enemy.

“There needs to be an enemy, to create an us and them dynamic. They identify and define the enemy and go into detail about why they are the opposition. In this case, it’s usually women,” she said.

But their arguments are not simplistic, they try and validate their hatred of women with clever narratives, justifying the baseless male superiority plight with actual physical and hormonal differences between the sexes.

Ms Willis said narcissistic men who blame women for their problems are often using them as a scapegoat.

“The men that I’ve worked with who are narcissistic and who have negative attitudes towards women have been hurt by potentially a mother figure or a caregiver,” she said.

“For whatever reason, that anger and deep hatred towards women, is born. It’s kind of like scapegoating really, like saying ‘my childhood was terrible and it’s all my mother’s fault’.”

Influencers, just like cult leaders, use this common enemy to unite their followers.

Next comes a feeling of superiority.

You’re part of something special

Followers of men like Andrew Tate are made to feel like they are part of a group that is better than everyone else.

A 2025 study published by the British Sociological Association analysed Tate’s content and found that 89 per cent of his videos weren’t directly anti-women rhetoric. An overwhelming majority of his work is focussed on the traditional and capitalist ideas of what it means to be a “real, powerful man”.

But the obvious implications of championing patriarchal ideas of manhood is that women are lesser.

In “Hatespeech or Tatespeech? Andrew Tate and the rise of the radical misogynist”, a journal article published in October, the authors highlight how patriarchy is not just about the control of women and non-binary people, but also about “alpha” men controlling other men.

They argue that Tate uses “virtual manhood acts” to go beyond reinforcing extreme gender binaries. Instead, his extremist content “actively recruit(s) men and boys through processes and pathways of radicalisation”.

Looking at the concept of “manhood acts” is a shift away from the concept of masculinity, which academics criticised as being too broad. It prefers a focus on the real actions done by men, and how they might elucidate problematic cultural norms.

In the case of Tate, the researchers found he employs both textual and visual cues to signal “a masculine self”.

For instance his tight fitting suits are both a symbol of wealth and a nod to “masculine ideals of bodily control and discipline”. Verbally, his persistent use of the term “alpha male” is like a call to his audience to remember why they are there, why they are special.

Tate’s content is like a guidebook, a how to win at life starter pack, how to “be an alpha like me”.

But it is not for everyone. Ms Willis said it is made for men who feel insecure.

“It’s people who are feeling dissatisfied, it’s people who are feeling insecure about their value and are lacking a sense of achievement,” Ms Willis said.

Ms Willis said followers of these types of figures tend to have a sense that there is a “special relationship” between themselves, the leader and the followers they are in alignment with.

“Once you become a member you get a special status. So you’ve got these people who are feeling pretty alone and not great about what’s going on in their world, and then suddenly they’re being treated as if they’re really special,” she said.

This sense of belonging is something Ms Montell said seems intrinsic to humans.

“Our behaviour is driven by a desire for belonging and purpose. We’re ‘cultish’ by nature,” she wrote.

The influencer therefore takes on an authoritarian role, and much like a cult leader they continue to socially condition their recruits, and derive pleasure from successfully manipulating their views.

Gym bros, protein and looksmaxxing

Voices like Andrew Tate’s have been all over the internet for years, but the rise of so-called “lifestyle” influencers targeting young boys and men, teaching them to “looksmax” has parents concerned.

Many videos are aesthetic day-in-the-life type stories, which often show unrealistic routines unattainable for the average working person, or school kid.

Others are more blatant, breaking down exactly what a man should eat to gain muscle and lose body fat, cut in with videos of the influencer themselves flexing their gains - their transformation.

The messages always boil down to the same thing. “I was depressed and lazy before I locked in, focussed on myself and finally reached my potential. And, you can too.”

“If you do what I say, if you buy what I tell you to buy, you will look and feel great.”

But tunnel vision lifestyle voices have been around forever too, right? At least in the era of daytime TV people were generally certified in at least one aspect of health and wellness (that didn’t stop projects like The Biggest Loser).

Online, the appearance of authority and lived experience seems to be enough to satisfy some young audiences that the content can be trusted.

And they achieve this by manipulating language, leaning into popular terminology that is really just another offshoot of the manosphere.

The richer the influencer gets, the more unattainable their lifestyle and content becomes. They can go to the gym everyday, they can afford premium protein powders, they can eat steak, eggs and avocado for as many meals as they want.

Much like a cult leader, they have different privileges to their followers.

Young people are not just seeing these message from one creator, they are scrolling and seeing many people parroting the same ideas.

This is the “illusory truth effect”, which originated from studies completed in 1977 at Villanova University and Temple University, and posits that repeated statements, whether true or false, are perceived as more truthful.

As gym bros repeat this message, they create a belief in the mind of their audience that their words are true. This reinforces a resolve to fit in with the online “majority” — to be part of something special, to be stronger and better — with no regard for the actual health of the influenced person.

The common enemy is of course a lack of discipline, but this depends on feelings of shame and wanting to be desirable.

The recruited become recruiters

In the context of the manosphere, once followers have become radicalised themselves, they might start taking their views out of the comment section and into real life.

While some dismiss the manosphere and say it has had little impact on the offline world, the BSA study found that misogynistic online behaviours inspired by Tate were translating into “real life”.

By bringing these attitudes from screens into the real world, followers might feel like they are taking the next step to becoming the “alpha male”.

Really, they are still being manipulated by the men they think are a source of empowerment.

By perpetuating male supremacy, the Tate fledglings gain their fangs.

How not to get hooked

For Ms Willis, the key to preventing people from falling for cult-like online spaces is early education.

She said providing people with healthy sources for the content they seek, like finances and sporting information, could stop them from falling in with the wrong kind influencers.

“It’s giving people honest information and but also educating them about the about the kinds of things that they’re being hooked with, they’re being tricked, really,” she said.

For younger audiences, Ms Willis said Australia’s social media ban is extremely important.

“Young people’s brains, developing brains, are being affected massively on so many different levels with social media,” she said.

“There’s nowhere near enough good that comes out of social media in terms of the harm that it’s causing.”

She said the danger of online recruiting is the scatter approach.

These modern cult leaders don’t need to choose their targets.

The algorithm will serve their videos to the people who are most likely to engage with them.