Midnight Oil: The Hardest Line is a potent reminder that art and politics can and should mix

There are those who don’t want to see politics mixed with art, sport and just about everything. And maybe art isn’t always political but often the best art is. Midnight Oil knew that.

At the opening night of the Sydney Film Festival on Wednesday, director Paul Clarke was explaining why the subtitle of his Midnight Oil documentary was The Hardest Line.

Over the shouts of Oils fans in the audience impatient for the film to start, Clarke said that in a world of compromises and practicalities, Midnight Oil never compromised. The band always took the hardest line and always looked for a fight.

It might have been strange for fans to heckle the filmmaker who spent more than five years making a documentary dedicated to the Oils, but their passion spoke to the power of Midnight Oil to still enrapture. And that the renegade spirit of the band lives on in their followers.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.It also spoke to the likely fact many of those fans had never before attended a festival opening night, which always starts with about 45 minutes worth of speeches.

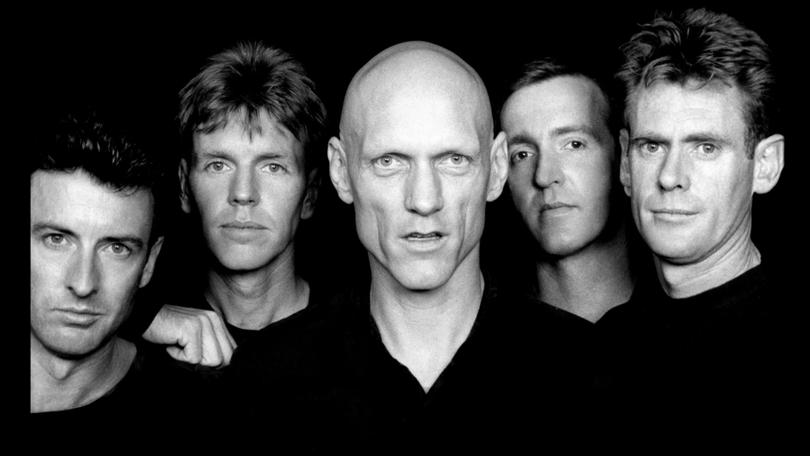

Midnight Oil: The Hardest Line is in some ways a standard music biopic but because the band was never standard, neither is the film. It charts the story of its formation through to the years at the height of its creativity and global recognition — and then the reunion after frontman Peter Garrett stepped away for his career in Federal politics.

Clarke’s film focused on what we’ve always known to be true about the Oils: That its art and its politics were inseparable.

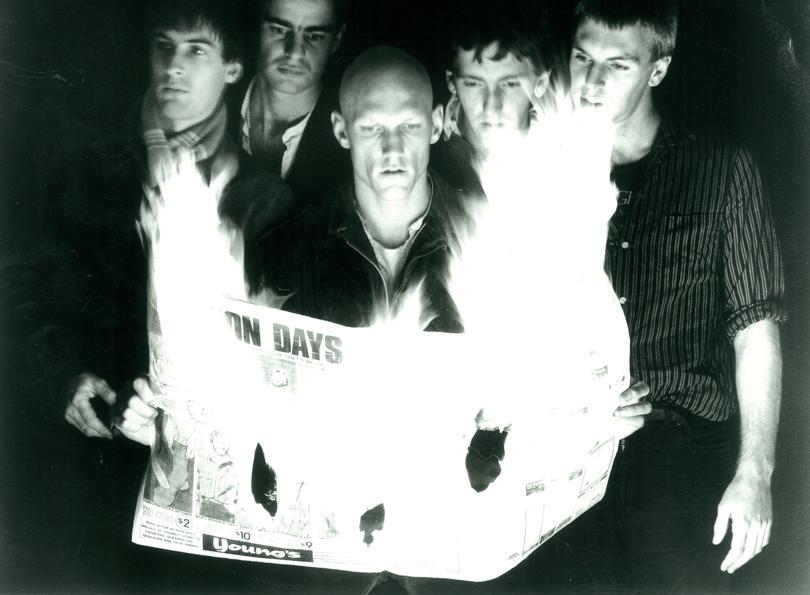

Born out of the heady days of 1970s social upheaval and institutional distrust, the Oils created music that spoke to the disaffection of young people who were sick of the old ways of doing things. Australia was the lucky country? Not for everyone. Even those north Sydney private school boys could see that.

They were agitators but a trip to Japan in 1984 made them activists. The resulting album, Red Sails in the Sunset, featured a mocked-up image of Sydney Harbour after a nuclear strike.

The experience of their time in Hiroshima and Nagasaki gave them a perspective on the destruction of nuclear power, and Garrett was soon at the top of the Senate ticket for the Nuclear Disarmament Party. Footage of fans outside an Oils show at the Hordern Pavillion featured one young woman who was asked why she would vote for Garrett. She replied: “I want to live”.

He didn’t win but it ignited his fire. Time spent in the Northern Territory on a joint tour with Indigenous artists Warumpi Band. That changed everything, again. The Diesel and Dust album featured Beds Are Burning, the song that catapulted the Oils to international stardom.

More significantly, it was the Oils’ declaration for First Nations people and the treatment of the original custodians of Australia. It was a humanist position, which meant it was a political position.

The Oils memorably performed Beds Are Burning at the closing ceremony of the 2000 Sydney Olympics, a rebellious moment that was kept under wraps until they emerged on stage, with literally billions of people watching, wearing black outfits with one word emblazoned across their bodies: “SORRY”.

It was an unambiguously political act in a febrile moment in Australian history. The then Prime Minister John Howard had obstinately and repeatedly refused to apologise for the government’s historical role in removing generations of Aboriginal children from their families.

The Olympics brand is notoriously anti-political, although whether anything or anyone can be apolitical depends on your point of view. For some, their mere existence is political while others who decry the “politicisation” of certain things are almost always coming from a position of status quo power.

Only the Oils could have co-opted the Sydney closing ceremony with a message that needed to be heard, giving authority and voice to a movement on which others had declined to lead.

Is art always entwined with politics? Maybe. Maybe not. That’s a conversation that is forever shifting.

Pablo Picasso painted Guernica in 1937 as commentary on the brutality of the Spanish Civil War, Erich Maria Remarque wrote All Quiet on the Western Front as an anti-war novel and Macklemore’s performance of Same Love at the 2017 NRL Grand Final was a rallying cry for LGBTQI rights.

But the Oils were outliers in how blatant and consistent they were about the politics of their art.

As the politics of the day shifted, when the agitation and optimism of their youth carried them in sync with social movements that gave way to rising conservatism, the band stayed true. Even if some would see Garrett’s career as a Labor politician as a compromise to his earlier activist days.

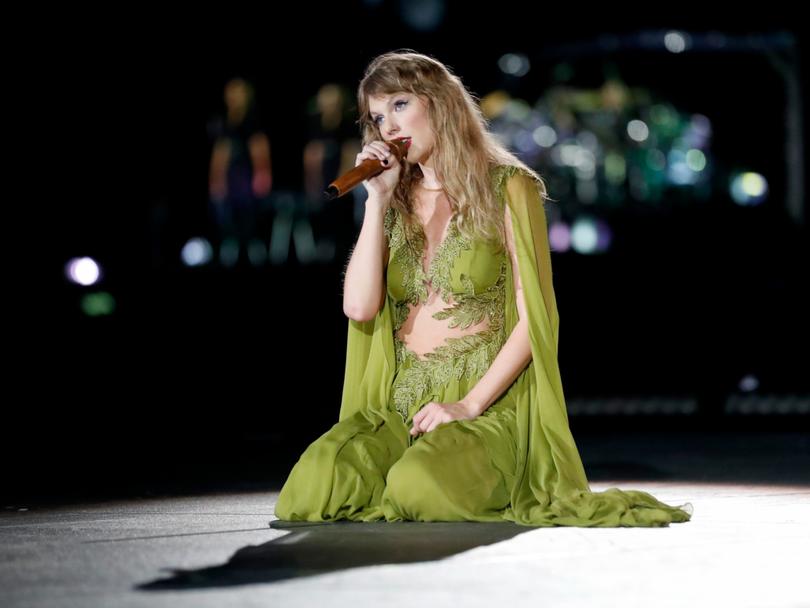

Successful artists are warned to keep their noses out of politics, lest they piss off half their fanbase. Throngs have pleaded with Taylor Swift to take a stance on issues for as long as she’s been popular (she supported Joe Biden in the 2020 US election), to use the power of her platform and influence.

But in the same way that no artist should be forced to publicly declare their politics, they shouldn’t also be cowed from doing so, for fear of losing their commercial appeal. Arguably, a commercial decision is still a political one.

Actors signalling their support for Palestinian statehood during the encore of a theatre performance shouldn’t be threatened and publicly bullied.

The Chicks (then The Dixie Chicks) shouldn’t have been blackballed by the industry when they say they say they’re ashamed of the Iraq War and George W. Bush.

Legendary screenwriter Dalton Trumbo should not have had to hide his name from his work after being branded a communist by the McCarthy-era witch hunt.

And N.W.A should not have been harassed by the FBI over a protest anthem that captured the frustrations of a marginalised community.

Maybe art isn’t always political but often the best art is.

Midnight Oil knew it and that will forever be their legacy. The subtitle of the documentary is also drawn from a lyric in their song, “Power and the Passion” – “Sometimes, you’ve got to take the hardest line”.

Midnight Oil: The Hardest Line is playing at the Sydney Film Festival and will be released nationally on July 4