Picnic at Hanging Rock and unresolved endings: Sometimes, it’s better to not know

There’s a lost chapter to Picnic at Hanging Rock but the answers were better left mysterious. Much like many Hollywood endings.

Did you know Picnic at Hanging Rock has a “lost chapter” which explains exactly what happens to the girls who disappeared up Victoria’s Macedon Ranges?

Joan Lindsay’s editor famously advised the author to excise it from her 1967 novel before publication, leaving generations of Australians gripped by the mystery.

Not knowing their fates is what made Peter Weir’s 1975 film so ethereal and creepy. Not knowing is what kept up the myth that there was a kernel of truth in the entirely fictional tale.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Three years after Lindsay’s 1984 death, that “lost chapter” was published as a standalone tome. It’s a sliver of a thing — a dozen pages and some additional discussion essays — and easy to miss tucked in between weightier books at the local council library.

That’s where I found it in 1997. I sat down between the stacks in that musty room and immediately devouring the answers. It was such a letdown. The revelation of what happened to Miranda, Marion and Miss McCraw dissipated the air of mystique surrounding Picnic at Hanging Rock.

If you don’t know it, resist the urge to google it. No good comes of knowing.

The twist ending is a grand tradition in storytelling and there are copious examples of when it’s pulled off really well.

It’s not about the “Surprise!” but the deep satisfaction of the combination of not seeing it coming and then having the puzzles fall into place. There should be clues, as your mind races to catch up. Yes, that makes sense now, it’s so clever!

Like when you discover (years-old spoiler alert!) that Fight Club’s narrator is Tyler Durden, that it was Earth all along or that there is no Keyser Soze. Remember the moment you realised Bruce Willis is a ghost? Whoa.

But it’s a tightrope and movies could just as easily give away too much or fumble the twist.

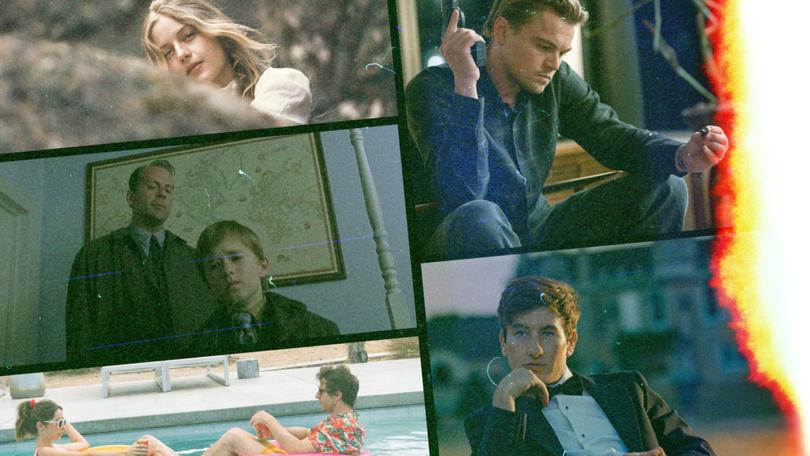

Saltburn is one of the guilty party. Emerald Fennell’s drama set among the rich and privileged aristocracy ends (another spoiler alert) with the middle-class boy Oliver Quick inheriting the Catton family’s wealth after they’re all dispatched.

By that point, you already strongly suspected he had a direct hand in their demise. The film explicitly outlining his manoeuvring, even flashing back to every moment, was so unnecessary. It had been telegraphing all the way through, so we already got there, we didn’t need the montage to explain it.

If you spoon-feed your audience a twist that was already heavily suggested, you make them feel patronised and impatient. We’re not dumb.

Part of the fun is the post-movie chat with your friends, or inhaling the online discourse. If you spell it out, you rob the audience of that experience. What’s there left to talk about?

Often, it’s better to not know for certain.

Did the spinning top at the end of Inception keep going, and therefore Cobb is still stuck in a dream, or will it stop and he’s living in reality? Cobb didn’t want to know and neither do we. Leave it open-ended, let each viewer decide for themselves.

In Mary Harron’s adaptation of American Psycho, she played up the satire and Patrick Bateman’s mania to suggest that maybe he hadn’t killed all those people, maybe he killed only the homeless man or maybe he killed no one.

That’s for you to resolve, and whether you take those murders literally or as the delusional hallucinations of a fracturing mind is something of a litmus test.

At the end of Korean thriller Park Chan-wook’s Oldboy, (spoiler alert) was the hero’s hypnosis to forget the fact his lover is his biological daughter successful, or is that uncomfortable smile on his face the revelation of something else?

One of the best rom-coms of the past decade, Palm Springs, a Groundhog Day-eque sci-fi tale, ends with the lovers seemingly escaping their time loop, but then you see those dinosaurs just off in the background.

It’s so open-ended, Palm Springs’ director Max Barbakow, writer Andy Siara, and actors Andy Samberg and Cristin Milioti all each have a different interpretation of that final scene. Four different possible endings, and the rest.

Not knowing is tantalising. Every variation is potentially the truth.

This usually works, unless it’s The Sopranos black screen. Some open endings will never satisfy.

But if you’re going to give answers, you’d better do it justice and don’t leave your audience in the darkest timeline.

You would bet a huge chunk of the Lost fandom would have preferred to have never known the island was some kind of purgatory-but-not-purgatory healing space and that everything from the past six seasons was essentially cosmic therapy disguised as a battle for existence.

Or something like that. Who really knows?