September 5: The 1972 Munich Olympics terror attack changed live broadcasting

A stone’s throw from the Munich Olympics athletes’ village was a sports broadcasting team who was on the ground when a terror attack was launched against Israeli competitors.

The 1972 terror attack at the Munich Olympics has been the subject of films before, but the one story that hasn’t been told is that of the people who captured it first.

On September 5 at 4am, as the Israeli competitors slept in their beds at the athletes’ village, eight masked men burst into their apartment, carrying assault rifles, pistols and hand grenades. What unfolded over the next day was nothing but brutal violence and fear.

Nine Israeli hostages were killed, along with one police officer and five terrorists who were members of Black September, a Palestinian militant group who were aided by West German neo-Nazis.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Not far away was the American broadcast team for ABC Sports, who were on the ground covering the Olympics. When the attack happened, they were there and switched from sports journalism to crisis reporting.

That frenzied 22 hours in the studio and in the field is the focus of September 5, a film starring John Magaro, Peter Sarsgard, Ben Chaplin and Leonie Benesch, and directed and co-written by Swiss filmmaker Tim Fehlbaum.

It was the first time that a terror attack had been broadcast live and the team had to, on the spot, contend with the ethics of what it means to beam these distressing images into homes halfway around the world, potentially showing executions or giving terrorists insights into the police operation outside.

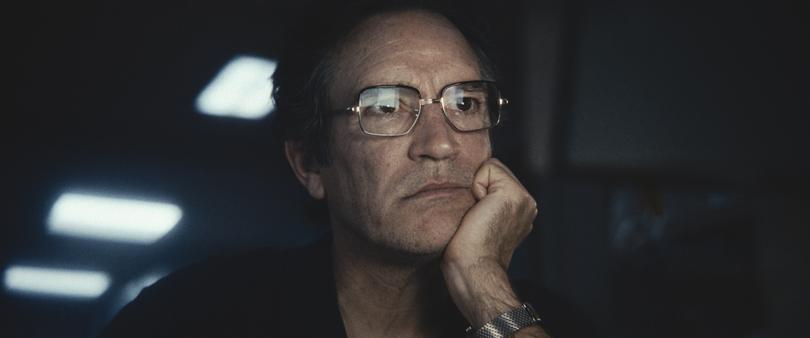

British actor Chaplin portrays one of the real-life people involved in the broadcast, head of operations Marvin Bader, who would go on to be inducted into the US Sports Broadcasting Hall of Fame in 2008 before his death in 2012.

“He was a legend,” Chaplin told The Nightly. “That was what was fun about it. These are behind-the-scenes people. It’s nice to pay tribute to them, really, because they’re very important people in their field, and it is a film about a specific field, and these people happen to be there on an awful day that changed their lives.

“Not as much as the people who are really caught up in it, but these people happen to be there covering it, and it changed their lives, it’s something that they always lived with, but they happened to be legends and loved their jobs.”

The pace of September 5 is one of its strongest attributes, to move through what is, ultimately, primarily scenes of stressed out people talking in a room, with kineticism and purpose.

That palpable sense of high stakes created by the film was also on set. It was shot on a soundstage in Munich in winter and the production had built the studio control room that was home to the story. It was designed to be claustrophobic, just as it had been for the real-life broadcasting team.

“It was a tight room,” Chaplin recalled. “They didn’t have walls that could fly out, (Fehlbaum) wanted it to feel tight, and it was tight with the number of people and actors in there.”

Chaplin said there were two handheld cameras and three people on each camera, and there was essentially a choreographed dance between the crew and performers.

“It was a very exciting shoot in a way, but it was quite demanding,” he said. “One, just in terms of it’s always demanding being in one location for weeks on end and with 10 to 12-hour days. It was full of smoky atmosphere and it was hot.”

Their characters were sweaty and while the make-up people sprayed fake sweat on the actors, it was a proper sweatbox on set and they never had to re-apply.

But even the cramped quarters worked in the film’s favour with the performances imbued with that authenticity.

Fehlbaum and the casting director were cognisant of the demands of the shoot and looked for actors who could rise to the challenge. Chaplin has a theatre background, as does Magaro and Sarsgard.

“It felt like theatre very much, and I like that. I like doing theatre, I like the shipmates, theatre is sociable, it’s fun, you want to be with other actors. Acting’s kind of lonely, you can’t do it when you’re not working.

“This film felt like a true ensemble.”

In September 5, Chaplin’s Bader is the voice of conscience, the man who’s pushing for double verification and asking the tough questions as the chaos swirls around him. Like predecessors such as The Post, Spotlight, Network and All the President’s Men, September 5 engages with the ethical dilemmas of its characters.

Chaplin described that day as a loss of innocence in more ways than one, and that the questions the film throws up about the broadcast are ones we still grapple with today, perhaps even more so.

“A very pressing question for all of our futures and the future of the planet is what we learned, what we lost, what are we losing with broadcasting everything live, with people who aren’t journalists.

“I mean, anyone who’s a journalist now is someone who wants to be a journalist and has a phone. This is that terrible moment that the question was born. There is something touchingly innocent about these people asking these questions, which I’m sure is still being asked by responsible journalists. Are those two sources verified?

“It is asking that question at a very important moment in our history as a species.”

September 5 is in cinemas on February 6