Tom Cruise 2025: Why Mission Impossible star just can’t quit cult life

Tom Cruise has a Messiah complex, and since he was 18 years old, has had an intense drive and certainty about the value of his brand.

There’s a well-known anecdote American Psycho director Mary Harron has told about Christian Bale’s inspiration for the titular sociopath.

By Harron’s account, Bale had seen an interview of Cruise on David Letterman, and he saw in Cruise this, “very intense friendliness with nothing behind the eyes”, and told the director this was the energy he wanted to channel.

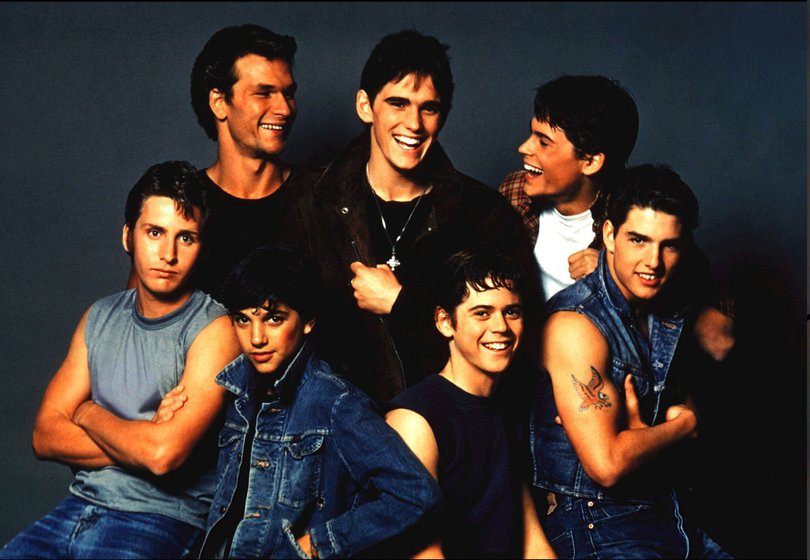

Cruise has been a magnet of the silver screen since he backflipped off that car in The Outsiders, the only actor in the large ensemble of up-and-comers who could pull it off, according to his co-star Rob Lowe.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Lowe once shared a story of when they were teenagers auditioning for the Francis Ford Coppola movie, and when Cruise discovered they were to share a room at New York City’s Plaza Hotel, he went “ballistic”.

Lowe didn’t tell this story as a window into diva celebrity behaviour, but to score that Cruise, at 18 years old and with nothing more than minor roles in three movies to his name, already knew who he was and who he was going to be, that he was, as Lowe put it, “the real deal”.

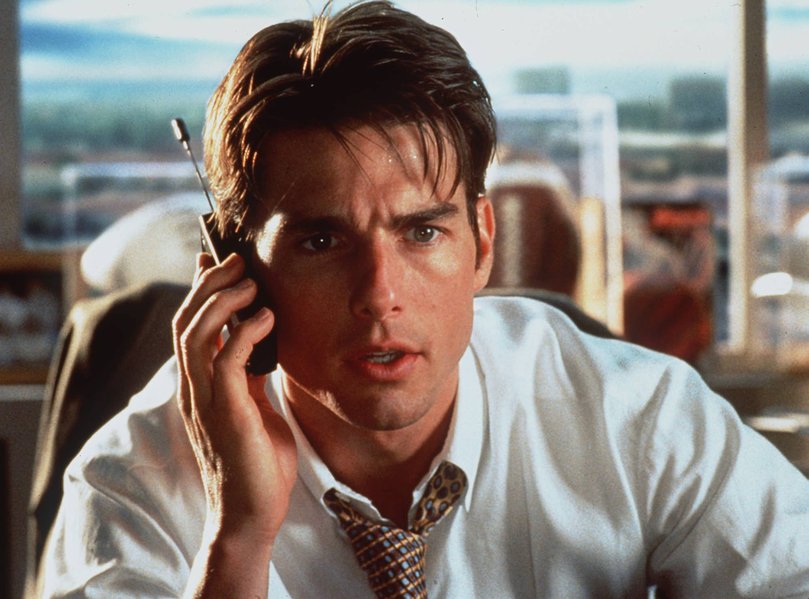

That’s the kind of intensity that has marked Cruise’s career for more than 40 years. With the release of Mission: Impossible – The Final Reckoning nabbing a franchise-best opening box office, Cruise is back on top. He is undeniably the world’s biggest movie star.

He sashayed down the Cannes Film Festival red carpet, grinned and posed at premieres in London and New York City. He was hailed as the saviour of the cinematic experience with his commitment to doing his own high-octane, eye-popping stunts, literally putting his body on the line so audiences can be entertained with a spectacle.

After 29 years as Ethan Hunt, it’s hard to tell where Cruise ends and Hunt begins. Tom Cruise is Ethan Hunt is Tom Cruise. That’s the mythology Cruise and his team have crafted since he dangled off the Burj Khalifa in the fourth film.

When the script of M:I8 thanks Hunt for saving the world time and again, and when multiple characters say that Hunt is only person who can defeat the blurry AI villain from destroying humanity in a nuclear holocaust, it’s a not-so-subtle nod reinforcing Cruise’s Messiah complex.

In case you missed it, Cruise is here to save the movie industry. As its self-appointed greatest champion, in an age when his compatriots straddle screens both large and small, Cruise has still never done TV or streaming, unless you count an episode of anthology series Fallen Angel he directed in 1993.

From HALO jumps to holding his breath underwater for six minutes, and hanging off planes, trains and automobiles, Cruise’s antics are reserved for the big screen. He’s not a compromise kind of guy – he fought Paramount when it threatened to release Top Gun: Maverick on streaming during the pandemic.

During Covid, he was photographed, mask on, at a cinema watching Christopher Nolan’s Tenet, and has posted pictures of himself holding tickets to see Barbie, Oppenheimer and Sinners. He showed up to support Twisters. Steven Spielberg told him he saved cinema’s arse, after Maverick’s $US1.5 billion box office haul.

The way he eats popcorn goes viral. Everyone in Hollywood wants to be on his Christmas cake list.

He was easily forgiven for swearing and yelling at crew on the set of Mission: Impossible 7 for breaking Covid protocols, because it was in the name of cinema. It’s because he loves the movies so much, you know? That’s a cult we can get behind.

If that leaked audio had come out two decades ago and not five years ago, it would’ve been a different story.

Last Friday, it was 20 years to the day when Cruise jumped up and down on Oprah Winfrey’s yellow couch, declaring his love for Katie Holmes. It was a moment of seeming pure adulation, but rather than sweet, it was cringe. It killed something in his allure.

A month later, in an interview with Matt Lauer, Cruise got into it with the now disgraced American broadcaster over anti-depressants. Earlier in the month, Cruise had criticised Brooke Shields, who said she used them to deal with post-partum depression, and when Lauer challenged him, Cruise got his hackles up.

With a defensive posture and a stern expression, he went in, “Matt, Matt, Matt, Matt, Matt, you’re glib, you don’t even know what Ritalin is”. He said Shields didn’t understand the history of psychiatry and that it was a “pseudoscience”.

These were defining moments in pop culture because no matter how charismatic Cruise was on screen, these two manic episodes brought to the fore the aspect of his celebrity the wider public were not so comfortable with – his Scientology faith.

The couch jump was one thing, and in isolation, might’ve just been that week’s punchline, although the timing of it coincided with the rise of YouTube, ensuring it would be played, replayed and parodied far and wide.

But everything Cruise-related was filtered through the context of his association with the controversial religious sect. The Lauer confrontation was rooted in Scientology’s opposition to psychiatry and psychiatric drugs.

Less than a year earlier, Cruise had fired his powerful publicist, Pat Kingsley, who had been with him since A Few Good Men, and hired his sister Lee Anne DeVette, another Scientologist. It was a short-lived decision. By the end of 2005, Cruise signed on veteran spinner Paul Bloch, but the damage wasn’t reversible.

Cruise had been a member of Scientology since 1986, introduced to it by his first wife, the actor Mimi Rogers. His faith didn’t become public until 1992 but by the early 2000s, he was one of its fiercest advocates.

David Miscavige, the church’s leader who has since 2007 been dogged by questions over his wife Shelly’s whereabouts, made a big show of being close to Cruise, and exploited his celebrity to further Scientology’s profile. In 2004, Miscavige created the Scientology Freedom Medal of Valor just to award to Cruise.

The Cruise controversy hijacked Spielberg’s War of the Worlds promotional tour and the actor was seen as “tarnished”. Until a clever, self-deprecating comedic cameo in Tropic Thunder in 2008, he appeared in only two films – Mission: Impossible III and Lions for Lambs.

Tropic Thunder gave fans permission to reconsider Cruise and he released a series of moderately successful movies (Valkyrie, Oblivion) but what emerged from that period is a different kind of actor.

Cruise had previously been a mainstay player across a range of genres, most notably dramas such as Rain Man, A Few Good Men, Magnolia, Eyes Wide Shut and The Firm, but since Valkyrie, the vast majority of his roles are action-driven.

He played Jack Reacher twice, the excellent Edge of Tomorrow saw him welded to a robot pack, in American Made, he portrayed a pilot who became a drug smuggler, and the box office disaster The Mummy (Cruise’s appeal is not bomb-proof) had him tumbling inside a falling plane.

He reprised the role of Maverick, and committed himself and the whole cast to filming every flying scene in actual F-18 jets in the sky, experiencing the full power of the G-force. It was a classic Cruise move.

From the fifth Mission: Impossible movie onwards, Cruise had worked with director and co-writer Christopher McQuarrie and the two of them had established a working dynamic in which the productions would be built around a series of elaborate stunts, and the script would come later, sometimes once cameras had already started rolling.

The Mission: Impossible movies, just like Cruise himself, had become something else – a new cult into which he could pour his focus, intensity and energy.

Every stunt had to be real, and he would do them himself. There would be no cheats.

The stakes felt real for the audience, and Cruise could remake his image as not just an actor playing an action hero but a goddamn actual action hero who could run like no one else.

In Mission: Impossible – The Final Reckoning, Cruise finds an excuse to take his shirt off more than once, revealing a buff body that belies his 62 years. In Top Gun: Maverick, he did the same, and he did it while in a scene with a raft of super attractive twenty- and thirtysomething co-stars.

It all augments this latter-day image of Cruise as the invincible, mass-appeal action hero who will never retire from being a movie star, as long as we can all forget about that pesky Scientology thing.

Mission: Impossible – The Final Reckoning, depending on who you ask and on what day, may or may not be the last instalment in the franchise, and his next project is with Oscar-winning Mexican director Alejandro G. Inarritu. Details are scarce but it could be the kind of film Cruise used to make, before he blurred the lines between himself and Ethan Hunt.

Is Cruise ready to be just as intense about something else? Can he make all movies, not just action or big-screen blockbusters, his new cult? There is a Top Gun 3 on the way, so any pending identity crisis has an off-ramp.

Cruise can’t stop being Cruise in the same way Ethan Hunt can’t stop saving the world.

He hasn’t spoken publicly about Scientology in more than a decade.