JOHN McDONALD: Western Sydney housewife Marikit Santiago combines faith, family and renaissance reboot

There’s something wild and uninhibited about Santiago’s work, which is broadly autobiographical but draws on the beliefs and history of the Philippines and the iconography of European Old Masters.

Marikit Santiago is a study in applied multiculturalism. Born in Australia to a migrant family from the Philippines, she has clung to her second-hand cultural heritage as if it were a lifeline to a history and a set of traditions that are richer than anything she’s been able to absorb while living in North Parramatta.

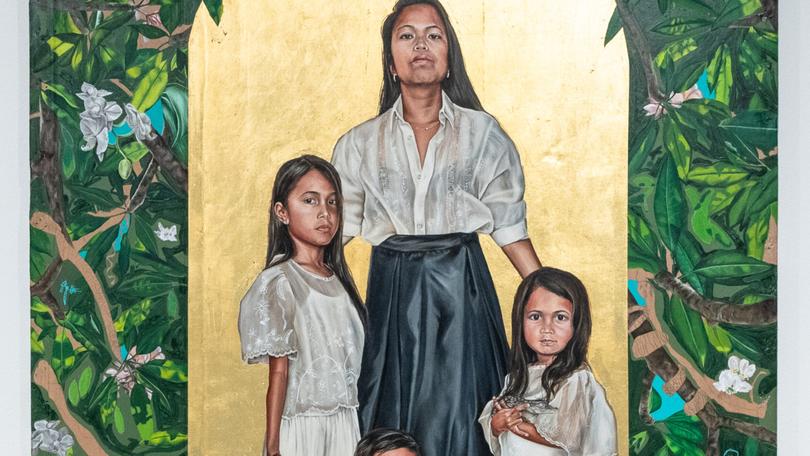

A mother of three children, aged six, eight and ten, she combines her work in the studio with a full raft of domestic duties and school pickups, but Santiago hasn’t allowed everyday life to strangle her artistic efforts. Instead, she gets the kids involved, encouraging them to draw and paint on her works, which she then calls collaborations. It may sound alarming, but it’s a low-level contribution that only adds another layer of exoticism to paintings that are baroque by inclination.

The title of her show at the Campbelltown Arts Centre borrows a line from the Catholic Liturgy: “We proclaim your death, O Lord And profess your resurrection until you come again”. It’s not the first time Santiago has drawn on the deep Catholic beliefs of the Philippines for titles and subject matter. She won the 2020 Sulman Prize at the Art Gallery of NSW with a painting called The Divine - a meditation on original sin, that featured her children with snakes and halos.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.I would have given her the Archibald Prize in 2023, for a self-portrait with the kids on gold leaf, called Hallowed Be Thy Name, which is included in this show. The Trustees were not persuaded but her fortunes changed last year when the AGNSW gave Santiago the La Prairie Award, which consists of $80,000 and a residency in Switzerland.

This is the most mysterious major art award in Australia, reserved for a woman artist, with the winner chosen apparently by decree. There is no competition and very selective media coverage. As far as I can see, a curator at the AGNSW simply nominates the lucky artist. The Swiss cosmetics company that sponsors the prize must approve of this state of affairs, but it leans heavily on the judgement of one museum professional. It’s a gift bestowed without a hint of democratic process.

Of course, if you’re the chosen one, the award must seem quite perfect. For Santiago it’s part of a dream run that has led to a succession of solo exhibitions in both commercial and public galleries, and inclusion in museum surveys such as the 2024 Adelaide Biennial. I believe the expression is: “She’s having a moment”.

One could be cynical about this sudden success and note how Santiago ticks all the boxes for contemporary institutional recognition. She’s female and non-Anglo Saxon, lives in Sydney’s western suburbs, and makes art that might be interpreted through the lenses of feminism or post-colonialism. Her status as housewife superstar and doting mum is also a plus.

I’m sure there are admirers of her work for whom these factors are crucial, but I’d like to think the main source of appeal was the painting itself, not the political frameworks it permits. There’s something wild and uninhibited about Santiago’s work, which is broadly autobiographical but draws on the beliefs and history of the Philippines and the iconography of European Old Masters.

For this exhibition she has borrowed from the AGNSW’s holdings of Renaissance and Baroque paintings to create her own, highly personalised versions of classic stories. Bathala and Diyan Masalanta, for instance, is based on Jacques Blanchard’s Mars and the vestal virgin (1637-38). In the earlier picture, Mars, in chest-plate and plumed hat, has come across the virgin sleeping under a tree, with one breast coyly exposed. We’re left to imagine the sexual encounter that will lead to the birth of Romulus and Remus, and the founding of Rome.

Santiago’s response to this painting is much raunchier. She and her husband, Shawn, are cast in the main roles. Both are naked and fully engaged, with Santiago’s avatar holding an apple in the manner of the Biblical Eve. The European scenery has been replaced by lush, tropical vegetation, while the characters have been recast as the Tagalog Creator god and the goddess of Love. Blanchard’s Mars will ravish the virgin while she sleeps, but Santiago’s Bathala is being seduced by a very active Diyan Masalanta.

This new version is more overtly erotic, but also slightly comical, as these two middle-aged people are hardly godlike. What’s most notable is the assertiveness of the image. Blanchard’s virgin is a passive object of beauty, who will never open her eyes while Mars has his way. Santiago’s goddess is the aggressive sexual partner.

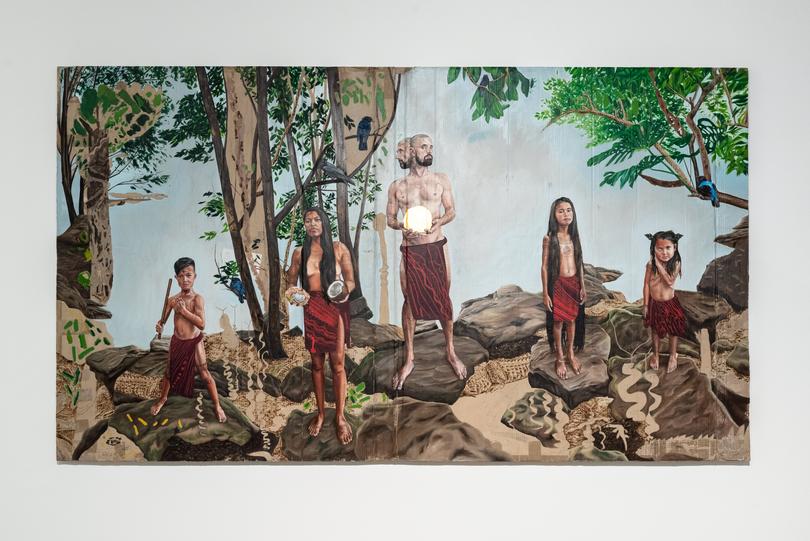

This kind of postmodernist play-acting is not new, but Santiago puts a lot of verve and imagination into her reworkings. Another painting, Mangkukulam, transforms Santiago, her husband and children into supernatural beings taken from Tagalog superstition. This time the reference is to Andrea Schiavone’s Mythological subject (c. 1560), a stagy tableau in which a set of mythological figures are lined up against a typical Renaissance landscape.

In Mangkukulam, Santiago’s kids are sitting amidst loosely brushed tree roots, dressed in their school uniforms. Her husband has his back to us and appears to be putting on a shirt, while the artist stands on the right side of the picture, holding a candle. The backdrop is the Parramatta River, complete with distant tower block. Once again, the work feels vaguely comical because of its incongruous mix of Philippines and classical mythology, combined with references to contemporary suburbia.

Both works I’ve mentioned are painted on cardboard, intended as a tribute to the countless cardboard boxes of goods sent back to the Philippines by friends and relatives spread all over the world. As a support, cardboard requires a good deal of preparation because it tends to absorb and deaden colour, as we see in paintings by Ian Fairweather. Santiago, who enjoys using the most vivid colour, is taking a risk in employing cardboard – albeit for conceptual reasons – rather than canvas.

Cardboard plays an even bigger role in this exhibition as part of a room-sized installation in which Santiago’s paintings are arranged within the confines of a schematic church, modelled on San Augustin in Manila. It has been designed by the artist’s father, Noy, who is an architect. In return, Santiago has painted portraits of her parents on the outside doors of the mock church. Inside there is an altarpiece in which we see the artist, her children and husband on three separate panels. The kids look as if they are posing for a formal photo, but Santiago has gone full monty again, as Eve/Pandora/Lilith – a most unlikely figure for a Catholic altarpiece.

There’s an awkwardness about such transgressive acts, as if Santiago feels she’s doing something really naughty. A similar awkwardness is present in her painting, which aims for a realistic image but often leaves figures looking clumsy and disproportioned. She has all the necessary skills but doesn’t employ them consistently, as the idea of a painting takes precedence over its execution.

This impression is emphasised by the long explanations the artist offers for all her paintings, and the odd decision to make a half-hour video of a family dinner the centrepiece of the show. The humdrum nature of the discussion only tends to diminish the mythical complexity of the pictures.

As installations go, the cardboard church fills the space in minimal way, while the potplants arranged around the gallery feel a little tacky. If Santiago could have planted a jungle it would have been a convincing statement. In such instances it may be better to do less rather than strive for the unattainable.

What one takes away from this show is the sense of an artist filled with energy and enthusiasm, striving a bit too hard to give her work a contemporary edge and ensure we understand all her ideas and sources of inspiration. But the main appeal of these autobiographical-mythological paintings, is the way they tap into that taste for operatic drama and neo-gothic excess one finds in so much art from the Philippines. Santiago may be Australian-born but she is completely immersed in the aesthetics of her ancestral home. She should cut back on the explanations and fully embrace that explosive craziness.

Marikit Santiago: Proclaim Your Death!

Campbelltown Arts Centre, until 16 March