Peter Godwin’s Space, Light & Time exhibition shows the reality of an overlooked major artistic talent

Peter Godwin’s admirers can never understand why his work isn’t currently hanging on the walls of all the public art museums. But the reason is simple - he’s a straight, white, male artist.

It’s a parlour game in the artworld to ask: “Who’s overrated? Who’s underrated? Who should be better known?” One artist who regularly features in these discussions is Peter Godwin, whose admirers can never understand why his work isn’t hanging on the walls of all the public art museums.

The answer to that question tells us why so many of these museums are struggling to attract audiences. To catch the eye of these aloof strongholds it’s not sufficient to be an outstanding painter – you have to be the right kind of painter. It also helps if you show at one of a handful of favoured commercial galleries.

Godwin doesn’t tick enough boxes. He shows with Defiance Gallery in Sydney, a name that strikes a jarring note in an art scene that rewards conformity. He is also a member of that much-derided species: the straight, white, male artist. Born in 1953, he has no chance of being considered cool. The nefarious crimes of history have allowed these beasts to dominate the permanent collections of our public galleries - an alarming situation for museum professionals determined to “decolonise” their institutions. They are addressing the problem by ignoring the old white guys and only buying work by artists with sound minoritarian credentials.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.In this view of the world, “quality” is far less important than “identity”, with the underlying assumption being that artists who are female, Indigenous or Queer are just naturally better. Centuries of discrimination based on race and gender are to be redressed through discrimination based on race and gender.

It’s bad luck for artists such as Godwin and his peers, who might claim they’ve never discriminated against anyone, but when policies are driven by ideology, no one is innocent.

I wish I could say this was a joke, but it is a dilemma museums have created for themselves and shown no willingness to address. Whatever high-flown morality now dictates acquisition policy, there is no simple correlation between identity and ability. By today’s standards of judgement, we would never have collected work by notable misogynists such as Rembrandt or Picasso.

The survey, Peter Godwin: Space, Light & Time was put together by Lucy Stranger for the enterprising Orange Regional Gallery last September. The second and final venue is Sydney’s S.H. Ervin Gallery.

In many ways, Godwin is an old-fashioned artist. He paints still life, interiors, landscapes, and the occasional portrait. He flirts with abstraction, but everything remains grounded in observation. The art he admires is reflected in his work – Goya, Roman frescoes, traditional Chinese landscape, Matisse, Braque, Ian Fairweather and Tony Tuckson. It’s an eclectic group of influences, but one can find traces of all of them in this show. Nothing is obvious or on the surface, the lessons have been assimilated into the pictures like fine threads in a vast tapestry.

By the time he had his first exhibition with Defiance in 2002, Godwin was almost fifty years old and had only shown sporadically, while working as a teacher. It was a revelation to many viewers for whom he was an unknown quantity; others had been following his work for a long time and looking forward to an exhibition. The event was a sell-out, and his popularity with private collectors has never diminished.

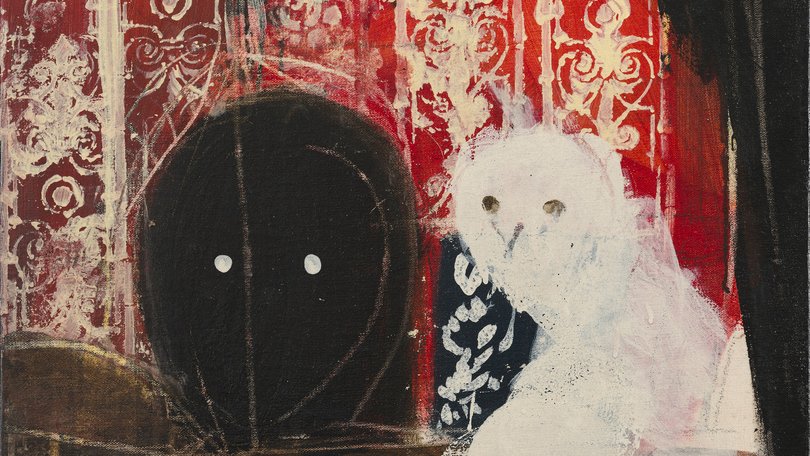

Until about 2015, a typical Godwin painting was a studio interior, in which still life objects stood out against large planes of black, broken by sweeping brushstrokes. Many of these paintings were in tempera – the medium used to paint frescoes in the Italian Renaissance – lending a dry texture to the surfaces.

A painting such as Night Window with Highland Shield (2011), is dominated by a massive slab of black, with a red-and-white shield mostly concealed behind a cream-coloured curtain that acts as a burst of light. The blankness of the window is offset, on the left-hand side, by a heavily patterned curtain. On a table we see two bright eyes of a tiny mask. These elements reappear in painting after painting, without ever growing predictable. They are Godwin’s answer to the dusty jugs and bottles that preoccupied Giorgio Morandi for decades.

The reason these repetitive paintings are so fascinating is mainly down to composition. One can sense the thought that has gone into the disposition of forms and objects to construct an image that holds the viewer’s eye and keeps asking questions. This is precisely what is missing from the much-hyped Julie Mehretu show at the MCA, in which paintings dissipate into a storm of abstract marks and lines which feel depressingly random.

Because the eye and the mind love order we’ll search for familiar shapes and patterns in the most unlikely places. Mehretu frustrates this visual instinct, but Godwin gives us plenty to think about. A slab of black is revealed as a window, but in purely compositional terms it’s a recessive plane that balances out a lighter area. The dynamic play of darkness and light energises every humble object in the painting. When Godwin feels a plane has become too oppressive, he might use the end of the brush to scrape a line into the surface.

These lines become important, as does the fluid quality of the paint, which admits light into each object, setting up a dialogue between translucency and opacity. The process may sound dry, but in visual terms it’s tremendously exciting.

In 2015, Godwin broke away from his routines to travel to the UK, where he made a series of gigantic carborundum prints, using a brush on the end of a broomstick to paint the schematic forms of mountains. Works such as Red Mountains, White Cloud (2015), a triptych of 2.4 X 3.6 metres, seemed exceptionally daring coming from an artist so anchored to the studio. The works owe a debt to Chinese landscape, but those old masters never drew mountains in red and green with loose, overlapping outlines.

A visit to the mountains of Guilin in 2018 inspired a series of large-scale landscapes in oil and acrylic, using subdued tones of black, brown and white. What’s remarkable about paintings such as Li River, Mountains and Waterfall (2018) is not simply the creation of atmosphere, but the way Godwin seems to have learned from every new body of work, harnessing elements from previous paintings but taking them in new directions.

In the same year he returned to the studio, but with a greater freedom. Nothing could have prepared us for Painter at rest – Twilight Studio (2018), with its blaze of light filtered through a curtain, engulfing objects in the foreground in a creamy haze. Just as surprising is Mask and Violin (2018), in which the crude suggestion of the nominated objects is placed within an all-engulfing field of black.

Godwin’s most recent paintings remain variations on a theme, exploring ways to capture darkness and light in the studio. This familiarity is important, as it allows him to forget about the subject, and burrow deeply into the material and metaphysical aspects of painting.

Conscious of the dangers of becoming too introverted, of delving too far down the rabbit hole, Godwin will paint a one-off picture such as a self-portrait, or After Fragonard (2002), a riff on that iconic French painting, The Stolen Kiss (1787).

Not long ago, most prominent artists might have worked in the same manner as Godwin – grinding away in the studio and the landscape, mixing experiment with consolidation. Today it’s not unusual for successful artists to have teams of assistants producing work under factory conditions. Once it was commonplace for artists to stick to the tried-and-trusted genres, without striving to make political points or align themselves with various interest groups, but this is now a path to oblivion.

It’s a choice as to whether we see art as a vehicle for social and political messages, or the way a creative sensibility engages with the world. The two are not mutually exclusive, but a great work of art always leaves us feeling that no matter how long we look, our options are never exhausted. Ultimately it may be those artists who can look past the obsessions of the present who will be most admired in the future.

Peter Godwin

S.H. Ervin Gallery, Sydney

Until 2 March