John McDonald: Art and all that is in between at the Islamic Arts Biennale in Saudi Arabia

The staggering quality on display at the Islamic Arts Biennale is a superb introduction to Islamic history

There’s a similarity about most biennales — seemingly random collections of work by international contemporary artists yoked together under the vaguest of themes. There are superior examples, more specialised or localised versions, but never has there been anything like the Islamic Arts Biennale (IAB), launched in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, in 2023.

I didn’t get to that inaugural event, but the second IAB is a show of staggering quality. Although there is a contemporary component, most of the 500 items on display are historical artefacts, some more than a thousand years old.

The show has its own suitably fuzzy subtitle — “And All That Is In Between”, a phrase that recurs at least 20 times in the Qu’ran. It’s a superb introduction to the history and meaning of Islamic art, represented by works of exquisite craftsmanship, spiritual and intellectual profundity.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.The exhibition is a key component of a Saudi global charm offensive, which has seen the Kingdom pour hundreds of millions into cultural infrastructure over the past five years.

Along with the oasis town of AlUla, which has become a major art site in the desert, there have been two Contemporary Art Biennales in Riyadh, and countless smaller projects.

The IAB may be the most ambitious of all the Saudi initiatives, because it’s incredibly daring to take a living religion as the raison d’être for a major art exhibition.

One might be able to get away with a Buddhist Biennale, but most other forms of worship would struggle for credibility. Can you imagine a western city hosting a Christian Arts Biennale?

Sydney’s annual Blake Prize for Religious Art, which has morphed into a prize for “spiritual” art, displays an unholy dread of conventional Christian imagery. If you want to be swiftly rejected from the Blake, paint a Crucifixion or an Annunciation.

What about a Jewish Art Biennale? Would it be the antidote to a rising tide of Anti-Semitic violence? The Israeli pavilion in last year’s Venice Biennale never managed to open its doors.

It’s a very different story for Saudi Arabia, which prides itself on being the centre of the Muslim faith and is eager to demonstrate it is no longer a hive of ultra-repressive Wahhabism.

The Saudis are happy to leave the hard-line reputation to their arch enemy, Iran, although this hasn’t prevented the inclusion of many items of Persian art and heritage. A phrase repeated several times in the catalogue is “the art of being a Muslim”, as if being a believer were a dilettantish, aesthetic choice.

After oil, the Saudis’ second biggest source of revenue is believed to be the Hajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca (or Makkah) that all good Muslims are expected to make at least once in their lives. Go to Jeddah at this temperate time of year, and you’re surrounded by pilgrms in their characteristic white robes.

The city is the historic gateway to the holy cities of Mecca and Medina (AKA. Madinah), and the venue for the Biennale is a vast enclosure where the pilgrims would gather. The site with its high, tent-like canopies dates from 1981, and is the work of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. It’s now home to a series of spacious new galleries in which the scenography has been handled by Rem Koolhaas’s OMA studios.

The show has four artistic directors: Islamic experts, Julian Raby, Amin Jaffer and Abdul Rahman Azzam, along with Saudi artist, Muhannad Shono.

They have divided the Biennale into four sections: AlBidayah (The Beginning), AlMadar (The Orbit), AlMuqtani (Homage), and Almidhallah (The Canopy).

There are also two permanent pavilions dedicated to Mecca and Medina, and a new architectural feature, the AlMusalla Prize, awarded for the best design of “a space for prayer and contemplation”. The winner was an elaborate woven structure by East Architecture Studio, of Lebanon.

The IAB is enriched by loans from over 30 institutions, from Timbuktu to Oxford; including the Vatican Apostolic Library, the Louvre, and the Victoria & Albert Museum.

One entire section of the show — AlMuqtani — features work from two outstanding private collections: the Al Thani Collection, and the Furusiyya Art Foundation.

Faced With such a vast trove I can’t dwell on details. Neither would it make much sense to write critiques of individual artefacts, as many of the items on display are works of devotion in which artists have been chiefly concerned with expressing their reverence for God. It just so happens that piety and beauty are inextricably linked.

A section devoted to Numbers — AlMadar — contains numerous books and manuscripts of a scientific and mathematical nature, including a first edition of Copernicus’s On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres (1543), on loan from the Vatican. There are astrolabes and other instruments from down the centuries.

Inevitably the IAB includes many beautifully illuminated versions of the Qu’ran, mostly collected in the AlBidayah section, which explores forms of sacredness. The bulk of contemporary works are installed in the open air, under the Hajj canopies.

This exhibition dispels some popular preconceptions about Islamic art and confirms others. The most egregious error is that Islam does not permit figuration — an idea instantly refuted by Mughal painting.

Scholars say there is nothing in the Qu’ran that forbids the depiction of the human figure, and nothing to that effect in the collected sayings of the Prophet, the Hadiths, that is not contradicted by another passage.

Another belief is that Islamic art is overwhelmingly preoccupied with geometry, and the sinuous vegetal forms we call the Arabesque, which combine plant imagery with the most precise calculation. This is confirmed by hundreds of items in this show.

Amid so many unique historical artefacts, it’s hard to go past two hand-drawn maps by Evliya Çelebi, a Turk of the 17th century, who spent much of his life roaming around the Middle East, satisfying his wanderlust.

For the first time, this show brings together Çelebi’s map of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, from the Qatar National Library, with his large-scale map of the Nile, from the Vatican.

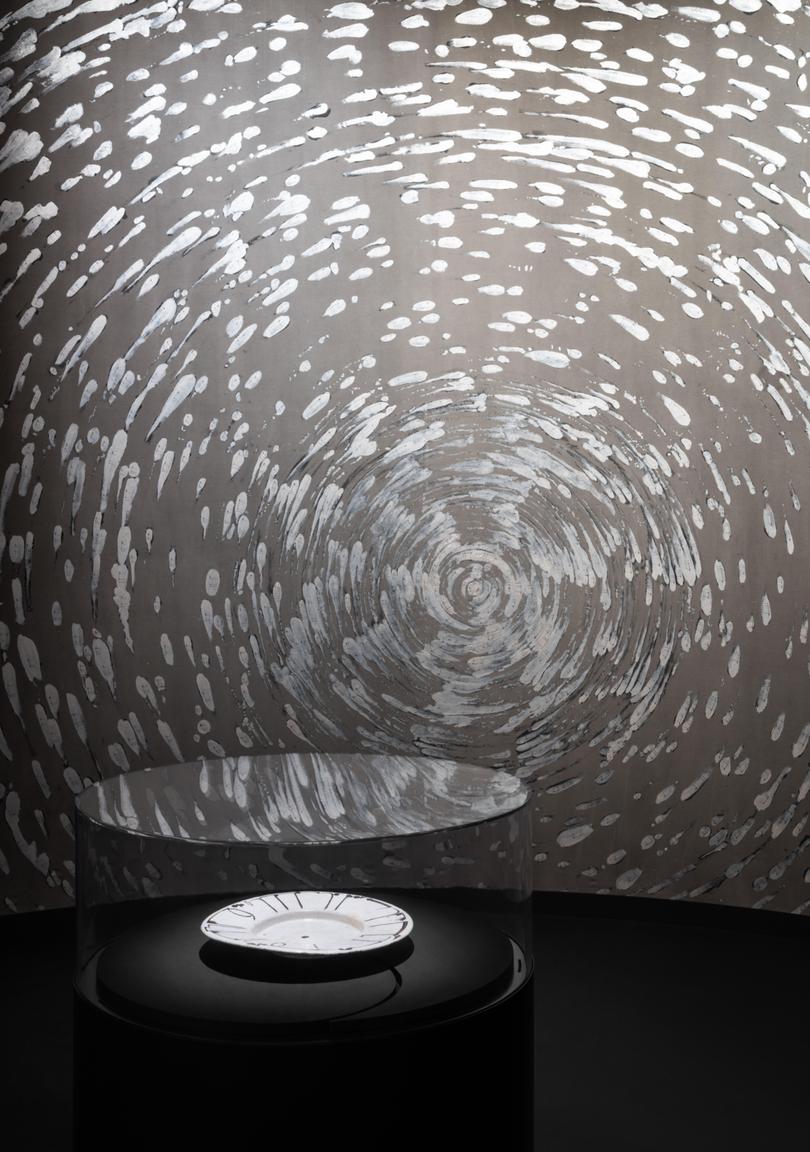

It’s difficult for the contemporary work to compete with the quality of the historical artefacts, but Italian artist, Arcangelo Sassolino has created a standout installation.

His Memory of Becoming is an 8-metre disc that turns slowly on a wall. The surface is coated in black industrial oil that trickles down from the centre of the disc, being subtly diverted by the rotating motion. Although it relates to the mystical void, there’s a tongue-in-cheek reference to the oil wealth that enables the Saudis to stage events such as the IAB.

A particular highlight is a vast room featuring the kiswah — a heavily decorated covering that is draped over the Ka’aba in Mecca. The cloth is suspended from the ceiling, in a display intended to instill a sense of awe and power.

Every year there is a new kiswah, with the previous one being cut up and widely distributed. This version from last year was left intact for the Biennale, and it’s a thrill to see it. Even though the cloth is machine-made, and not to be compared with more intricate hand weavings, it’s a dramatic blend of blacks; soft, tangled calligraphy, and silver overlay.

Along with the kiswah, one may see a madraj — a set of steps on wheels that leads up to the Ka’aba, and two keys to the door of the shrine, dating from the 13th and 18th centuries. There’s even a set of footprints of the prophet, Ibrahim. For a non-Muslim, it’s as close as any infidel will get to the Holiest of Holies.

Such displays would have been inconceivable in Saudi Arabia a generation ago, when the clerics specialised in issuing fatwas against all forms of pleasure, including art, movies, music and dancing.

Today, the country is seeking to become the most popular tourist destination in the Middle East, with the resources to make it a real possibility.

The overriding message of this Biennale is that Islam today is something to be admired, not feared. It is to be viewed as welcoming, not insular; peaceful, not angry.

The truth is that Islam, like all global religions, is many different things. It may be a stretch to call it an “art”, but after spending two days with this marvellous exhibition, I was fully persuaded that if you want to acheve wonders, you’ve got to have faith.

Islamic Arts Biennale 2025: And All That Is In Between

Western Hajj Terminal, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

Until 25 May

John McDonald flew to Jeddah as a guest of the Islamic Arts Biennale