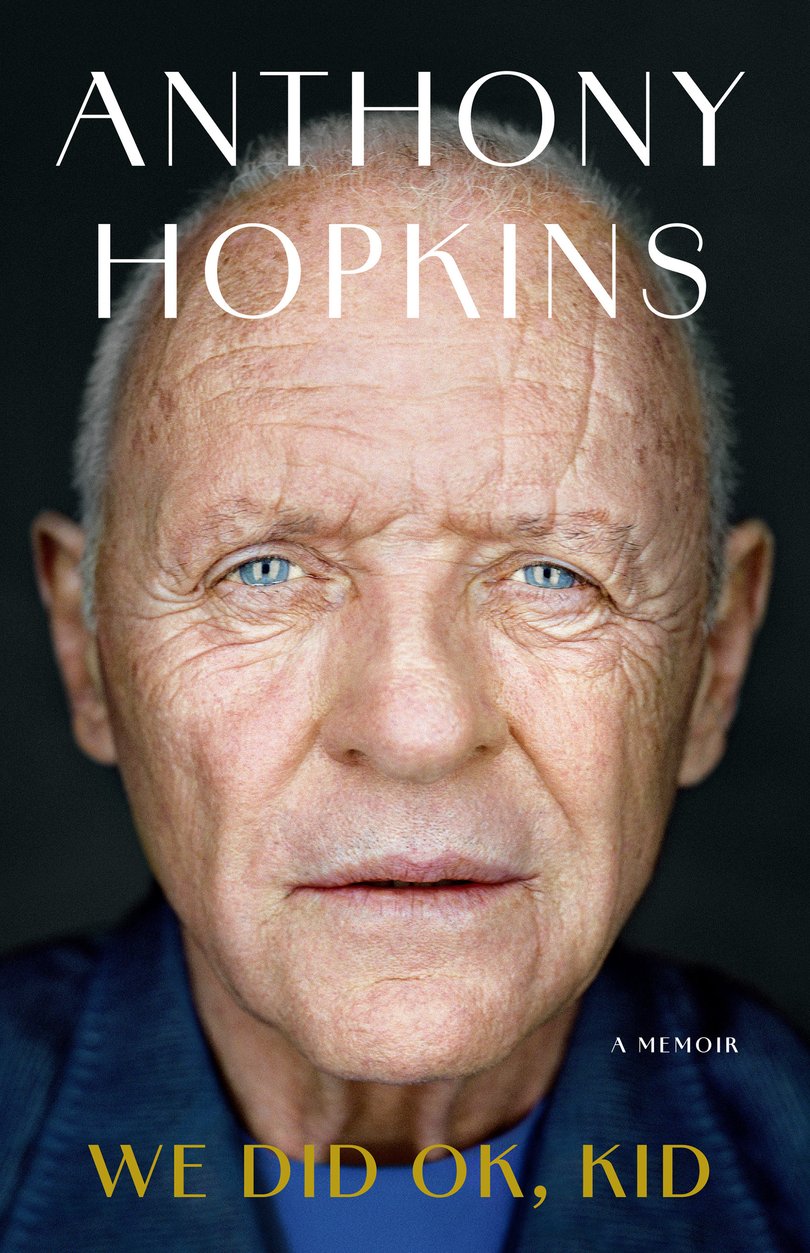

THE WASHINGTON POST: Oscar winner Anthony Hopkins’s new memoir, We Did OK, Kid, is a page-turner

WASHINGTON POST: Anthony Hopkins’ talent was not immediately apparent. Nicknamed Elephant Head for his large noggin, the actor remembers his grandfather lamenting, ‘what a pity there is nothing much in it’.

Reading Anthony Hopkins’s memoir, a page-turner with the humble bragging title We Did OK, Kid, about a life and career spanning more than 100 films, I couldn’t help thinking about the actor’s 2021 best-actor Oscar for The Father.

It would be his second win, after receiving a statuette for his portrayal of Hannibal ‘The Cannibal’ Lecter in Jonathan Demme’s serial-killer thriller The Silence of the Lambs.

Though best known for that 1991 performance - which Hopkins writes was inspired by Bela Lugosi’s Dracula, Joseph Stalin, an early acting teacher at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art and a spider on the wall of his father’s bakery - his work in The Father, as a man struggling with dementia, is considered by many to be his career best.

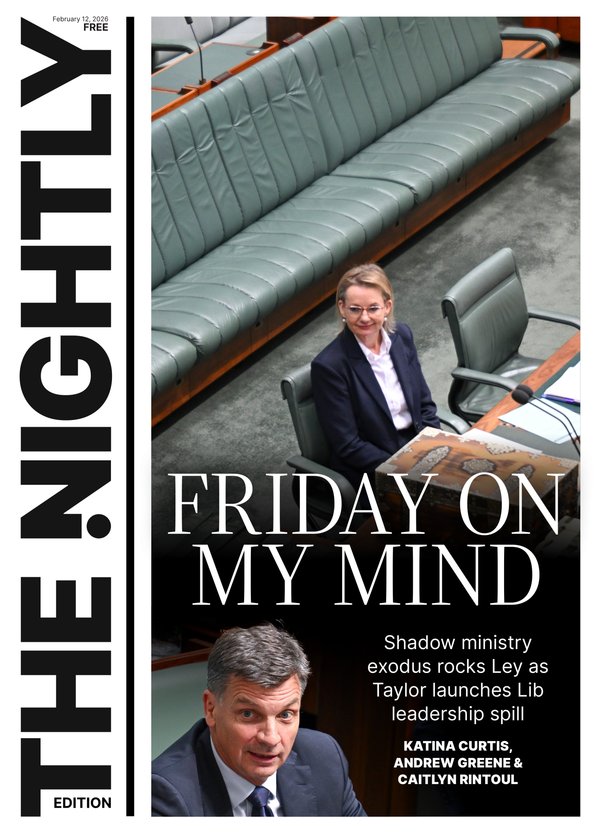

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.The film is still his most highly rated on Rotten Tomatoes.

Having skipped the ceremony out of COVID considerations - also possibly because the late Chadwick Boseman was considered a shoo-in for Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom - Hopkins posted a gracious and somewhat sheepish morning-after thank-you video from his homeland of Wales.

In it, he sounded almost as stunned by his upset win as the rest of the world: “At 83 years of age,” he said, “I didn’t expect to get this award. I really didn’t.”

A tone of incredulity also pervades the narrative here, in a story that begins in Port Talbot, Wales, where Hopkins grew up the son of a baker: a poor student who struggled with classwork, a class clown and a bit of a dreamer who annoyed family members with his slowness.

Nicknamed Elephant Head for his overly large noggin - ironically a boon on the silver screen - Hopkins remembers his grandfather lamenting, “what a pity there is nothing much in it.”

Talent was not immediately apparent.

Nevertheless, Hopkins writes of being bitten early by the acting bug.

After a school screening of Laurence Olivier’s Hamlet, he recalls that “a force had broken into the centre of whatever I was.”

Still later, after meeting Richard Burton, a fellow Welshman and already a successful stage actor in London, a youthful Hopkins would think to himself, “that’s what I want to be.”

His first good review, he recalls, followed a recitation of the Lord’s Prayer, after which his first-grade teacher praised him to Hopkins’s mother. In high school, Hopkins recalls being asked to recite John Masefield’s poem The West Wind before a room of fidgety adolescent boys.

When he concluded, he was gobsmacked by the reception: “no smirks, no sneers” and his teacher’s assessment, tempered by British reserve: “Thank you. Rather good.” Hopkins’s love of poetry remains to this day; his book includes an appendix featuring 15 examples of the actor’s favourite verse.

But something wasn’t quite right, he says: “I felt a bit out of my mind. Seventy years later, I still often feel that way, what people describe as not right in the head - not insane, but slightly removed from reality.”

He learns to calm the “ticktock of voices” in his head by studying statistics and details, repeating the word “terrazzo” and, later, by drinking to excess.

Motivated by a diagnosis of thrombosis, he eventually quit alcohol in 1975, but not before walking out on his first wife and their infant daughter, Abigail.

Two more marriages would follow, including to his current wife, Stella, with whom he lives in Malibu, California.

While living in New York and honing his skills onstage, he reports that he suffered from a phobia of walking on sidewalks, lest he be hit by a person jumping from a building. His skill at memorisation, both screenplays and decades-old conversations - a gift for an actor and a memoirist - is prodigious.

On one level, We Did OK, Kid charts a conventional path, from obscurity in regional theatre to the heights of Hollywood celebrity.

Yet this story is more concerned with the inner journey than the outer one. Just as he began to find success, he writes, “I’d never felt surer of myself as an actor, although I was also going to increasing extremes to feel in control of myself as a person.”

Gradually, you might start to wonder, as you encounter the litany of symptoms, including what Hopkins calls his “lack of emotionality”: Could this guy be on the spectrum?

So many of his performances - Magic, The Silence of the Lambs even The Remains of the Day - feature characters who hide behind an unreadable facade.

It’s what critic Manohla Dargis, in her review of 2007’s legal thriller Fracture, called the actor’s “most familiar” trick: “a blank face capped by a hint of a shiver-inducing smile.”

In a 2017 interview, Hopkins revealed that he had, in fact, been diagnosed with “high end” Asperger’s syndrome.

Eventually, in We Did OK, Kid, he gets around to this, though he now backpedals: “Even if the world might prefer I accept the Asperger’s label,” he writes, “I’ve chosen to stick with what I see as a more meaningful designation: cold fish.”

What is revealed here is a mind that works methodically, if idiosyncratically. Acting, Hopkins writes, “is a process of eliminating, uncovering, discovering, and discarding.

Start at the peak and gradually peel away the leaves and the weeds until you get to a naked place that feels right.” Reading a script, he says, is like “picking up stones from a cobblestone street one at a time, studying them, then replacing each in its proper spot.” He applies the same approach to autobiography.

Hopkins, who will turn 88 on New Year’s Eve, has a resume spanning Merchant Ivory to Marvel, yet in every performance - including one of his most recent, Sigmund Freud - you can almost hear the gears turning. Now, quoting the poet W. Yeats, he turns his analysis to himself:

“When you are old and gray and full of sleep

“And nodding by the fire, take down this book

“And slowly read, and dream of the soft look

“Your eyes once had, and of their shadows deep.”

“That is my role now,” he concludes, “to sit by the fire and remember.” We are the better for it.