The movie cheater’s guide to ‘must read before you die’ books

Of course you should read the classics of the Western literary canon, but if you’re short on time or patience, these screen adaptations capture their source material.

There are two reactions to any “100 books you must read before you die” list – guilt and smugness.

You’ve either really fallen behind on your literary consumption (don’t worry, it doesn’t make you a philistine), or you’re all over it and you can feel culturally superior to the rest of us spending our time scrolling through Instagram reels.

There are certain works of fiction that are just accepted as a must-read in the western literary canon, that will be referenced repeatedly, whether in The Simpsons or at pub trivia, or were so influential as to be a bedrock for its genre.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.But if you don’t have the time, or you’re just lazy, a perfectly valid life choice, many of them have screen adaptations that capture the essence of the book, and are bloody great films.

The criteria of this list means there are exclusions, books that either don’t have a screen version to match its significance (the novels of Martin Amis, Salman Rushdie, Haruki Murakami or Kurt Vonnegut, for example) or have departed from the source material (Mary Harron’s film of Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho, Greta Gerwig’s of Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women) so that you’d still need to read the book.

It’s also, not exhaustive, but a jumping off point.

SENSE AND SENSIBILITY

Jane Austen is a favourite for filmmakers because she wrote such compelling characters and so keenly observed the social dynamics of romance, courtship and class. Ang Lee’s 1995 movie with Emma Thompson and Kate Winslet tells Austen’s story of the Dashwood sisters as they contend with their reduced circumstances as well as a pair of dishy men.

BLADE RUNNER

Philip K. Dick was among one of the most influential sci-fi writers of any era (along with Isaac Asimov, Jules Verne, H.G. Wells, Frank Herbert), and his short story Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, he parses the empathy line that distinguishes humans and robots, something Ridley Scott picked up with his visually imaginative adaptation, Blade Runner.

THE ROAD

If you read a Cormac McCarthy novel, chances are, you’ll feel a little more grim about humanity’s future, especially The Road which makes a convincing argument for not surviving the first wave of any catastrophic apocalyptic event. This bleak tale of a father and son trying to beat the odds was made into a film by Australian director John Hillcoat with Viggo Mortensen and Kodi Smit-McPhee, and it’s just as brutal as the book. You don’t need to read and watch both, once is enough.

ATONEMENT

Ian McEwan’s 2001 novel is so delicate yet powerful in its exploration of truth and manipulation, class, desire and regret, that it’s astonishing that anyone was able to adapt this story about 13-year-old Briony Tallis whose lie in the summer of 1935 sets off a series of events there is no coming back from. Joe Wright does exactly this, and he cast a then baby and now four-time Oscar nominee Saoirse Ronan in the lead. Incredible film.

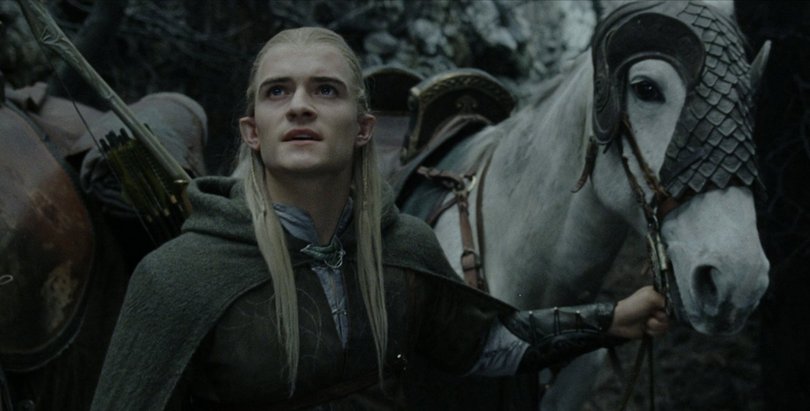

LORD OF THE RINGS

It’s a big commitment to read all of J.R.R. Tolkien’s 1000-plus-page epic spanning the perilous journey across Middle Earth to defeat Sauron and his evildoing ways. It might take the length of a flight to Japan to finish Peter Jackson’s cinema trilogy, but his films are rendered with such loving detail, thrills and the sight of Orlando Bloom’s Legolas sliding down a set of stairs during the battle at Helm’s Deep.

TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD

The character that inspired thousands of baby (and dog) names, Harper Lee’s progressive hero, Atticus Finch, stood for decency and humanism in the face of prejudice and hate. Never mind the 2015 release, Go Set a Watchman, billed as a sequel but was actually a draft of Mockingbird. Gregory Peck brought this paragon of justice to life in Robert Mulligan’s masterful 1962 film, a reflection of the righteousness and frustrations of fighting the good fight.

THE BIG SLEEP

You can’t have any discussions about hard-boiled detective fiction without mentioning Raymond Chandler’s novel, and the same goes for film noir and Howard Hawks’ 1946 adaptation. In Philip Marlowe, Chandler distilled the disillusionment against a corrupt city and institutions of power and wealth, which Humphrey Bogart beautifully encapsulated. Even more, his sizzling on- and off-screen chemistry with Lauren Bacall.

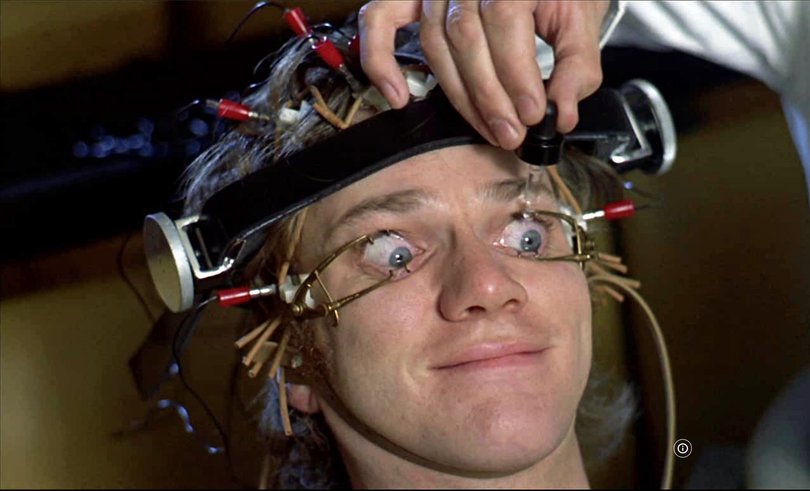

A CLOCKWORK ORANGE

Anthony Burgess’s dystopian sci-fi may be a small book in size, it is gargantuan in the ideas swirling within its pages – even if it takes a while to get used to his specific lexicon, although there is a glossary you can consult. The violence of Burgess’s book about disengaged youth on a crime spree was adapted by Stanley Kubrick, who uses almost balletic choreography to represent Alex’s delinquency. A revelation.

PRIDE & PREJUDICE

It’s a truth universally acknowledged that every generation will get its own screen version of Pride & Prejudice, and there will soon be another starring Emma Corrin and Jack Lowden, to be written by Dolly Alderton. But it will have a hard time besting the 1995 five-part BBC miniseries with Colin Firth and Jennifer Ehle, which captures the thorny dynamics between Elizabeth Bennett and Fitzwilliam Darcy. That version inspired Helen Fielding to write Bridget Jones’ Diary.

1984

A strong argument could be made that George Orwell’s 1984 is the most influential novel in shaping modern ideas about totalitarian rule, censorship and the breakdown of fact-based reality. Never underestimate the power of fiction to be searingly truthful. If you would rather see than read about the terrifying caged rats encounter, then Michael Radford’s adaptation starring John Hurt as Winston Smith will truly give you the creeps.

ROMEO & JULIET

Franco Zeffirelli’s 1968 film of William Shakespeare’s Romeo & Juliet is widely considered to be the definitive screen version of the doomed young lovers’ tale, and it is certainly a sumptuous adaptation with a luminous Olivia Hussey. The subsequent lawsuit from Hussey and Leonard Whiting alleging sexual abuse, harassment and fraud does colour the whole thing. Baz Luhrmann’s film, despite updating it to a 1990s setting, actually captures the youthful exuberance of young love, and the wasteful destruction of old family feuds.

HENRY V

Given how accomplished it was, it’s easy to forget now that Henry V was Kenneth Branagh’s directorial debut at the tender age of 28. He would go on to make another four Shakespeares but Henry V always loomed large. It’s no easy feat either, with the Bard’s history plays more challenging to adapt, but Branagh staged a punchy St Crispin’s Day speech, the mark of any successful rendering of Henry V.

REMAINS OF THE DAY

The transcendence of Kazuo Ishiguro’s Remains of the Day is in what’s not explicitly said – Mr Stevens is the epitome of English butlers and would never, ever allow himself to express anything that could interpreted as feelings. He was so devoted to the dignity of his post and an established order, that he allowed his chances at meaningful connections to slip away. James Ivory’s film version, starring a superb Anthony Hopkins, was a perfect adaptation of Ishiguro’s story.

TINKER TAILOR SOLDIER SPY

If Ian Fleming’s spy novels were full of thrills (and deeply problematic representations of all minorities), then John le Carre’s were complex portraits of not just its characters but the flawed and compromised worlds in which they live. Tinker Tailor, inspired by Kim Philby and the Cambridge Five captured the grey areas of Cold War espionage, and Tomas Alfredson’s 2011 film starring Gary Oldman was a vibey and twisty masterpiece.

WAR OF THE WORLDS

Steven Spielberg’s sci-fi epic may not have the subtext of H.G. Wells’ groundbreaking 1898 novel, with his alien invasion tale standing in for commentary on the predatory nature of the British imperial project, but it encapsulates the expansive ambitions of Wells’ story. With Tom Cruise as the lead, Spielberg changes the location from England to the US, and stages one of the most impressive, widescale sets committed to screen – the Boeing 747 crash – which you can walk around on the Universal Studios’ backlot tour.

CHILDREN OF MEN

While P.D. James was known primarily for her detective novels featuring the sleuth Adam Dalgliesh, her 1992 novel Children of Men was a rich textured nightmare vision of a dystopian future of mass infertility. It is nothing less than the extinction of humanity, and that nihilistic fate has had a chilling effect on freedom. Alfonso Cuaron’s 2006 adaptation captures the heady mix of loss, resignation, defiance and hope of a world that is all too possible.

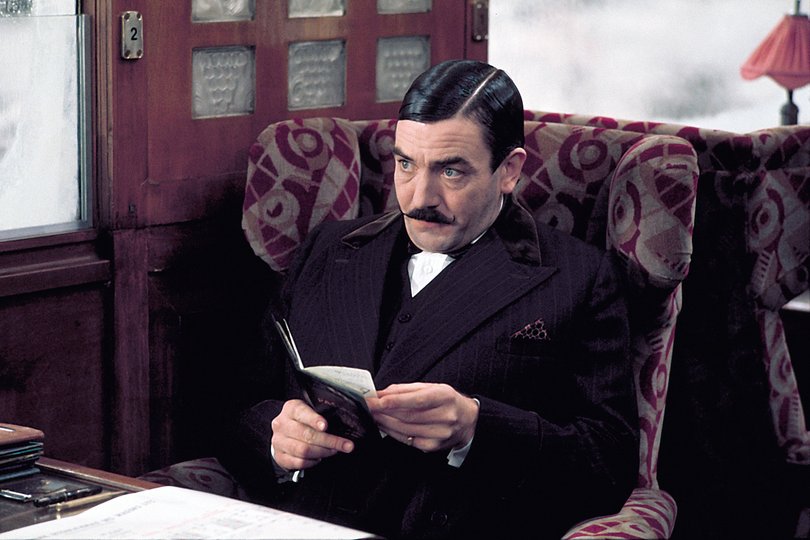

MURDER ON THE ORIENT EXPRESS

Agatha Christie’s many wonderful detective stories have been turned into screen projects for TV and film, but the primo example is still Sidney Lumet’s faithful 974 adaptation of Murder on the Orient Express. There’s a playfulness in Albert Finney’s Hercule Poirot, and the cast of suspects are portrayed by the likes of Ingrid Bergman (who won her third Oscar for this role), Lauren Bacall, John Gielgud and Sean Connery.

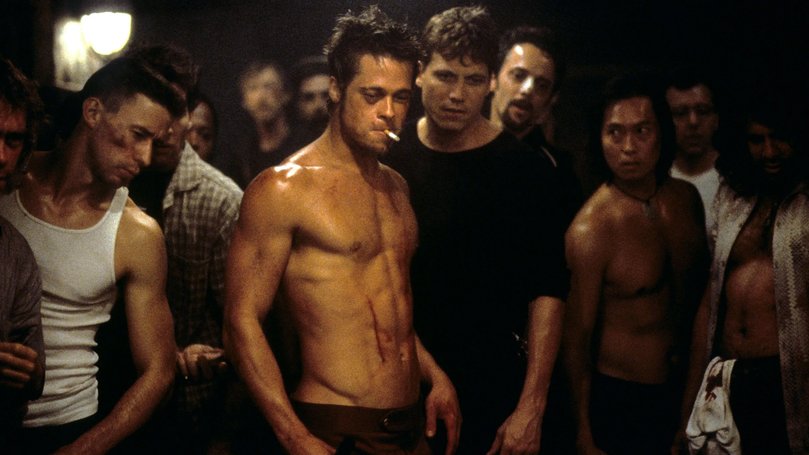

FIGHT CLUB

Do you remember the first time you ever read Chuck Palahniuk’s book or watched David Fincher’s film of Fight Club, and, hopefully, no one had spoiled that jaw-dropping revelation at the end? It was a punch in the face, the climax of a bonkers and provocative story that explores the emotional deadening of late-stage capitalism and the dehumanisation of individuals in a hyper-consumerist world.

BRIDESHEAD REVISITED

Before Saltburn and Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mr Ripley (which has had three excellent adaptations), there was Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited, a 1945 novel about the an outsider traversing the world of much richer friends. The lush 1981 miniseries, starring a gorgeous Jeremy Irons, captures the multifaceted entanglements of an unevenly matched relationship between Charles Ryder and his Oxford chum, Lord Sebastian Flyte.

MY BRILLIANT FRIEND

Named after the first of Elena Ferrante’s acclaimed Neapolitan Novels (there are four in total), this Italian and American co-production is a luxuriant and patient adaptation. The series evokes Ferrante’s brilliant, vivid prose and characterisation of two women, who became friends as girls in post-war Naples, and how their lives diverged as they navigated an Italy constantly challenged by change. The show ran for four seasons, from 2018 until last year.

PERSEPOLIS

Persepolis is not your typical graphic novel. Marjane Satrapi, an Iranian émigré who now lives in France but grew up between Europe and her homeland, was 10 years old when Islamic fundamentalists overthrew the relatively progressive and modern government and Persepolis is a lively memoir of her youth, dealing with the monumental challenges of growing up as a girl in Tehran. With Vincent Paronnaud, Satrapi adapted her book into an Oscar-nominated 2007 animated feature.

IF BEALE STREET COULD TALK

James Baldwin was one of the great American writers whose work captured the joys, pains and complex dynamics of being Black in a country that could be cruel and violent to their very existence. If Beale Street Could Talk was his fifth novel, an exquisite Harlem love story turned social horror when one of the characters is falsely accused of rape. The headiness of the romance, the heartache of the injustice is all there in Barry Jenkins’ soulful and urgent film.

PICNIC AT HANGING ROCK

Joan Lindsay was always coy about whether her seminal novel was based on a true story (it wasn’t) because it suited the myth of the story to leave the question open. Did a group of school girls and their teacher really vanish in the eerie Hanging Rock in Victoria’s Macedon Ranges? Peter Weir not only brought out the ethereal vibe of Lindsay’s book, and its subtext of the conflict between so-called English civilisation and the untameable Australian landscape, he created an instant classic of the Australian New Wave.

ANNA KARENINA

Obviously we should all read one of the Russian classics, but they are very heavy, both figuratively and literally (tip: One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn is a breezy 144 pages). Considered one of the great romances in all of Western literature, Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina is also a wider exploration of Russian society and progress, especially the contrast between those in the city and those in rural areas. Greta Garbo’s 1935 version is generally considered to be the canonical film version, but for a modern take, there’s also Joe Wright’s 2012 movie starring Keira Knightley.