Bridget Jones and Carrie Bradshaw: A tale of two city girls and the fantasies they sold their audience

Bridget Jones and Carrie Bradshaw both stormed on the scene as two 30-something city girls selling us a fantasy of excitement, love and friendship. Where did those dreams end up?

They live on either side of the Atlantic but there was more that unites Bridget Jones and Carrie Bradshaw than that which divides them.

Both characters stormed into our lives as 30-something single women out to conquer a city, or at least survive it.

They both worked in media at the tail end of the final boom era, loved to write about their experiences (Bridget in her diary, Carrie in her column), had a close group of friends with one token gay guy (Tom and Stanford), had dating mishaps, and were hopeless in the kitchen.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.They both married the on-and-off big love who would unexpectedly die in middle-age, leaving them with grief and a not-inconsiderable fortune (Big, as a finance guy did quite a bit better than human rights lawyer Mark, although don’t forget Mark’s parents had that posh country house and even posher accents).

For women, and not just white, middle-class Gen X women, Bridget Jones and Carrie Bradshaw represented a pop culture fantasy of living a big life filled with colour, hijinks and the pursuit of love and happiness.

Both their stories also came to an end this year with what looks to be the final Bridget Jones movie, and the upcoming conclusion to Carrie Bradshaw’s fourth act, And Just Like That.

Almost three decades later, what was that dream they sold?

Both characters were born out of mid-1990s newspaper columns turned novels as thinly veiled avatars of the women who created them, Helen Fielding and Candace Bushnell.

In Britain, it was the final years of conservative rule and change was in the air (Tony Blair and his New Labour brand would be elected two years after Fielding’s first column in The Independent), and in the US, Bill Clinton had come to power but was not yet tarnished by the sex scandal.

It was a time of hope and renewal in both countries and over the rest of the decade and into the new millennium (Sex and the City premiered in 1998, Bridget Jones’s Diary was released in 2001), women in western cultures agitated against and broke from the age-old expectations of wifedom, motherhood and being ordinary.

Artists such as David Lynch interrogated the rotten underbelly of these idealised suburban milieux where crime and darkness was as prevalent as in the city. Making it out and moving to the suburbs was never the goal for Bridget Jones and Carrie Bradshaw, whose cities were hubs of culture, excitement, parties, drinking, hangovers and friends.

You could be young and single, and having a brilliant and messy time in the city (Bridget lived near Borough Market, close to London Bridge, and Carrie in Manhattan on the Upper East Side), and for your life to have as much meaning as the smug marrieds.

Yes, they both wanted love, but they didn’t want a small, contented life.

It was always a fantasy though, and realities like housing, a living wage, global affairs, environmental catastrophe, ageing parents and terrorism rarely punctuated their worlds. No one baulked at the price of cocktails in New York City and London – and it’s steep.

Bridget Jones and Sex and the City also reinforced a version of capitalism that equated artificial standards of beauty with success, which were wrapped up in access to money and status. Both characters rarely litigated this pernicious social system.

Sex and the City, in particular, lived in a bubble of excess consumption, while Bridget Jones always battled her weight despite being two sizes smaller than the average in the UK.

It just so happened that almost every character in both worlds never seemed to financially struggle.

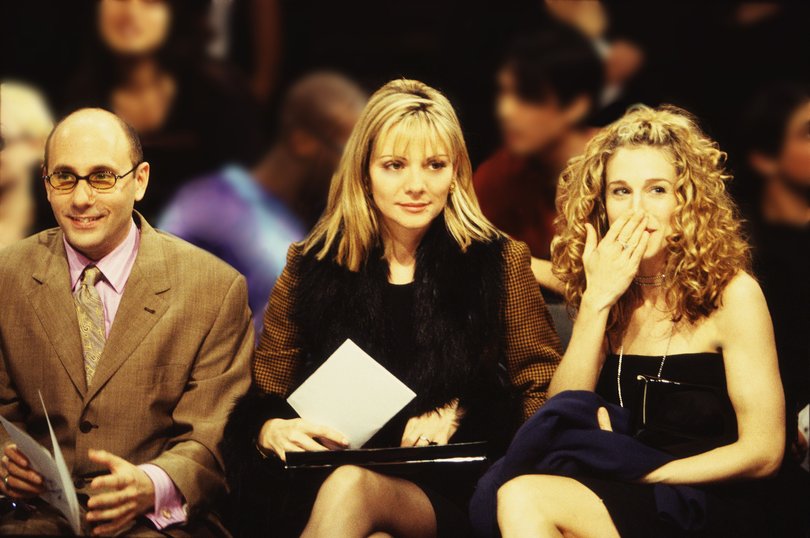

Samantha had her own PR firm, Miranda was a high-powered lawyer, Charlotte worked in art and then married a wealthy divorce attorney. Jude is an investment banker, Tom had a one-hit wonder music career and Shazza, well, we don’t know what she did but she wasn’t in social housing.

Characters lived in townhouses with dining tables large enough for elaborate dinner parties, or hosted birthday shindigs in fancy clubs and landscaped gardens.

But it was a fantasy, right?

Bridget Jones and Sex and the City were escapism, but as long as they kept it to a level of semi-relatability on an emotional level, we could overlook the more glaring offences.

At some point, it’s not so much the characters diverged as they entered middle-age, as the shows and films did.

Bridget Jones’s Diary had two quite terrible sequels, Edge of Reason and Bridget Jones’ Baby, but then came roaring back this year with Bridget Jones: Mad About the Boy. The title and the marketing is something of a misdirect, putting at the centre possible futures with two new men in her life.

That’s not really what that film is about. Bridget may end up with Scott Walliker, a teacher at her children’s school, but the person she learnt to love was herself.

After Mark’s death, Bridget went through a years-long period of mourning and her “getting back out there” has less to do with looking for another mate and more to do with moving on after a great loss while still holding space for her history.

The character had matured while remaining quintessentially the kooky, warm, optimistic and somewhat neurotic person she’d always been.

Bridget got another happy ending, as did the people in her life, including Daniel Cleaver, a character who had grown but not changed.

The dream Bridget Jones was ultimately selling was self-fulfilment, and the trappings of wealth were part of the texture of her life, rather than the point.

That final scene in which her nearest and dearest were crammed into her lovely albeit not enormous home (maybe Mark’s parents are still kicking around and her kids have yet to inherit their pile) reinforced that her friends, more than any man, were the greatest loves of her life.

With two more episodes left of And Just Like That, it’s hard to predict what Carrie’s ending will be but the three seasons we’ve seen so far suggests we shouldn’t expect too much.

This is a series that got further and further away from reality so the fantasy it’s selling is no longer even desirable. Does anyone really want to live in a huge Gramercy Park duplex that has no rugs, and in which you have to keep your high heels on? Only a masochist.

Carrie’s story may still end with a bow on top, but And Just Like That shattered the goodwill built over decades. Her world seems flat, a caricature of a New York glamour girl whose wardrobe is still the most exciting room in her home.

Even going out to a regular dinner involves a costume change more suited to the Vanity Fair Oscars after party.

And Just Like That’s portrayal of middle-age resembles nothing that any of its viewers could recognise. One of the few relatable beats – LTW’s dad dies – ends up being a farce when the series forgot that it had already killed him off, but then “explained” that one was her stepdad. Did anyone buy that?

In Bridget Jones, the flashback scene to her father in hospital had real resonance, a scenario familiar to many.

It’s not that And Just Like That is trying to sell the same dream as it did in 1998 (Fun! Glamour! Sex!), it’s that it didn’t evolve with its audience or the world. Instead, it’s offering up a funhouse mirror version of New York City that exists only for the 0.01 per cent. Read the room.

Carrie’s friends are still her number one, but even those dynamics don’t have the same ease as they once did. It always feel as if each individual is just talking aloud rather than to each other.

We still want to live in Bridget’s world, but we don’t want to live in Carrie’s.