Lizzie Borden axe murders could be the next Netflix Monster season

As far as nursery rhymes go, the Lizzie Borden one is on the macabre side.

“Lizzie Borden took an axe, and gave her mother forty whacks, and when she saw what she had done, she gave her father forty-one.”

Even in childish sing-song, it’s an evocative image, and the Lizzie Borden story has captured imaginations for over a century.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.So it’s not surprising that the king of sensationalist crime, Ryan Murphy has reportedly chosen it for a mooted fourth season of Monster, the anthology series that started with Jeffrey Dahmer and followed it up with the Menendez brothers case.

The upcoming third season will be about serial killer Ed Gein, also known as the Butcher of Plainfield, and had been the inspiration for Psycho’s Norman Bates.

Borden is a rare figure in history as very few women have gained the same level of criminal notoriety as men. It’s one of the most infamous murder stories of 19th century America, and at the time, had been widely covered in the national press.

Perhaps what’s most striking about her story is that she, ultimately, got away with it – unless, of course, you believe she didn’t do it.

First of all, the nursery rhyme wasn’t correct. Abby Borden wasn’t Lizzie’s mother but her stepmother, and she was struck 18 times. Lizzie’s father Andrew was hit 11 times. Also, it wasn’t an axe but a hatchet.

Lizzie was born in 1860 to Andrew and Sarah Borden in Fall River, Massachusetts, a town 80kms south of Boston. Her mother died when she was a toddler and three years after that, Andrew remarried Abby. Lizzie had an older sister, Emma, and they both lived at home.

On the morning of August 4, 1892, just before 11.10am, Lizzie yelled out to the family’s live-in maid, Margaret Sullivan, to quickly come downstairs because she had found Andrew dead on the sofa, his head battered and blood still seeping out.

Not long after, Abby’s body was discovered in the second floor guestroom, violently hacked to death. It was later established that Abby had been killed first and Andrew about 90 minutes later.

The sequencing of the deaths was important – because Abby died first, her estate passed onto Andrew, and then went to the Borden sisters. If it had been reversed, Andrew’s estate would have ended up with Abby’s family rather than his daughters. At the time of his death, it was valued at $300,000 or, in today’s terms, over $10 million.

There is dispute over whether Lizzie was in the house at the time of the killings. She claimed she was in the barn at the time of Andrew’s murder, and one witness said they spotted her leaving it at 11.03am.

But there were several inconsistencies in her account, and reports of suspicious activities after the killings. First she said she had heard a noise before she re-entered her house, then she backtracked and said she heard nothing. She initially told the maid her stepmother had been called away by a sick friend, but then pivoted and said maybe she was upstairs.

The investigators said they found her calm and poised – although a suspect’s collected demeanour has been used as a sign of guilt, this has since been thoroughly debunked.

In the basement of the house, police found two axes, two hatchets and a hatchet head with a broken handle. The latter appeared to have had ash and dust placed on the head, to make it seem as if it had not been used for some time.

Two days later, Lizzie was caught burning a dress, to which she said it was because it had become ruined with paint. It was discovered that she had purchased from a pharmacist prussic acid (hydrogen cyanide) the day before the deaths, but Lizzie claimed it was to clean a fur cloak. This was ultimately not admissible at trial.

The police were also accused of not being thorough with their investigation in the immediate aftermath. They neglected to search Lizzie’s room until days later.

At an inquest convened four days later, Lizzie contradicted herself on the stand and sometimes refused to answer, but this was also put down to the morphine that had been prescribed to her by the family doctor, which may have confused her.

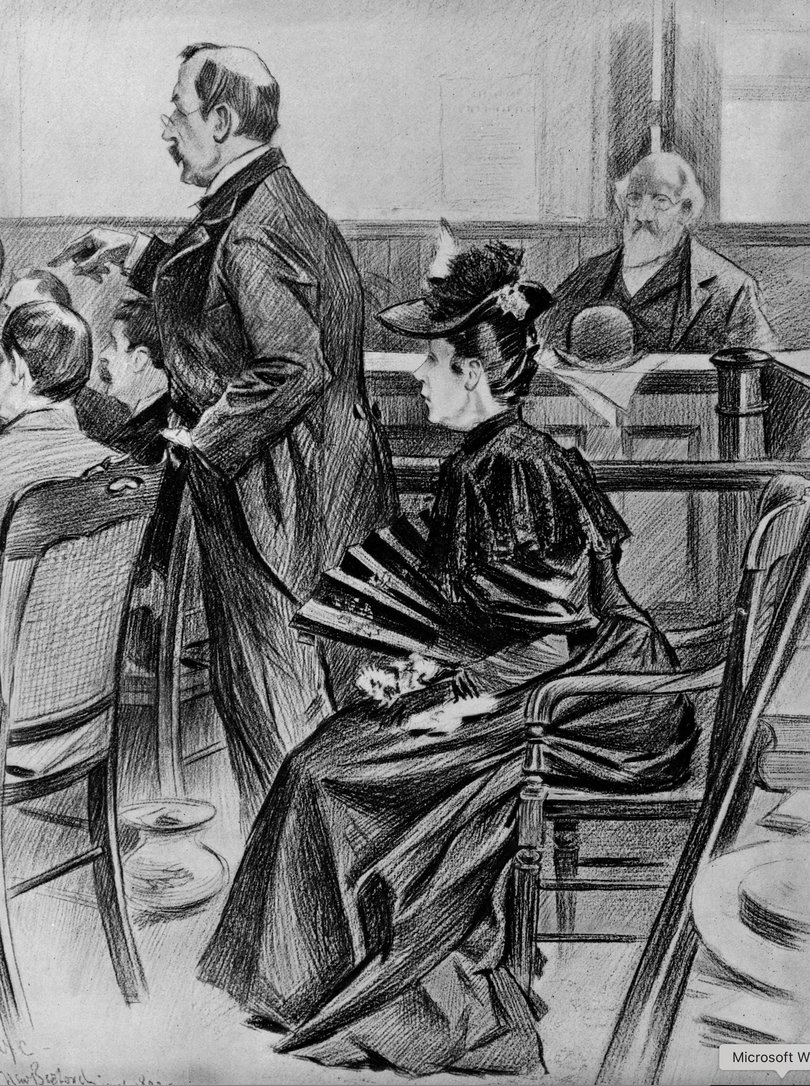

The trial itself did not take place until June the following year, and by then, her case had piqued national attention. Lizzie had her defenders, who attested that a good Protestant woman of her class could not possibly possess the moral turpitude required for such heinous acts. The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union and suffragists both came out in support.

The defence presented Abby and Andrew’s skulls as evidence during the trail. The sight of the remains caused Lizzie to faint.

The jury of farmers and tradesman, some with daughters the same age as the accused, acquitted her after half an hour of deliberations. No one else was ever charged over the murders.

Lizzie was set free, but in the 130 years since, her name has become legend, not as a triumph of justice but as a parent-killer who got away with it.

She has been the subject of plays, books, amateur investigations, songs, TV shows, movies in which she was played by Christina Ricci and Chloe Sevigny, and, of course, that nursery rhyme.

After the trial, Lizzie and her sister Emma moved to a ritzier neighbourhood called The Hill, but the house in which the murders took place is now a bed and breakfast attraction in which you can stay overnight including in the room in which Abby died.

Some say the house is haunted.