Sunday Reed is not just a supporting character in Sidney Nolan’s story

Most Australians would recognise Sidney Nolan’s Ned Kelly paintings but few of them would know of Sunday Reed’s contribution to them. A stage production wants to rewrite that story.

On the first floor of the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra, there’s a series of artworks that always attract a small crowd.

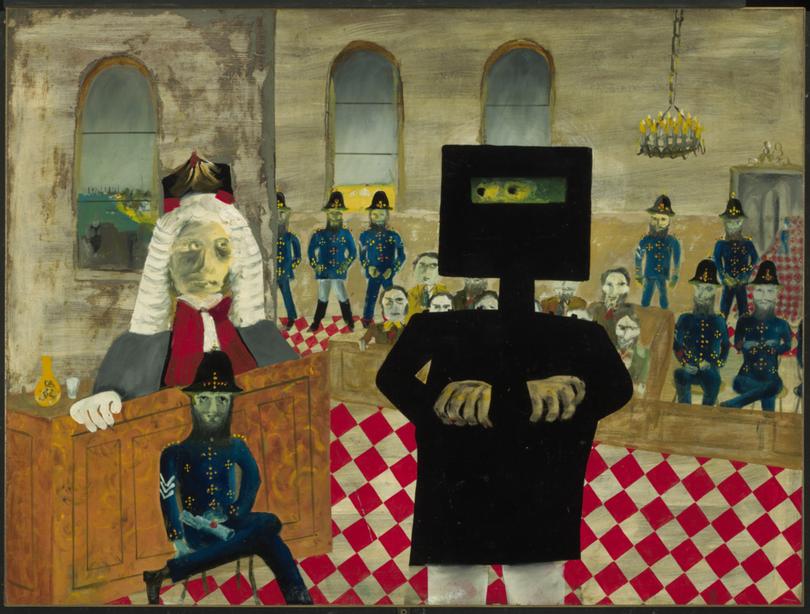

The slight flurry of activity is hard to miss and your gaze is inevitably drawn to the 26 paintings arranged across a vast swathe of wall. They’re vivid and energetic, almost like snapshots of a familiar tale, a story that is fundamental to a tenet of Australia’s national identity.

Sidney Nolan’s Ned Kelly paintings are among the most iconic visual legacies of Australia’s art history. But for everyone who has, at the very least, glimpsed these works in person, in a book, or on the internet, what do they know of the woman instrumental to their creation?

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.At the NGA, there is an accompanying note on display to Nolan’s frames — “Gift of Sunday Reed 1976”. Standing in that space, each time someone glances at those words, Reed is but a footnote in Nolan’s story.

Commissioned by the Melbourne Theatre Company, Sunday is opening a new season this week at the Sydney Theatre Company. The stage production places Reed where she belongs, at the centre of her own story, as more than a famous man’s muse.

Born to a prominent Melbourne family, the Baillieus, in 1905, Reed and her husband John established an artists’ circle from the 1930s onwards. At their Yarra River home at Heidelberg, they hosted modernist artists, including Joy Hester, Sam Atyeo, Albert Tucker and Nolan.

It was more than a patron-artist relationship as Sunday, John and Nolan’s personal lives became entwined. Nolan wasn’t the only person to be caught in the Reeds’ sexual web. Bedhopping was common at Heidelberg, but Nolan’s decade-long liaison with them was the most consequential.

During the menage a trois, Nolan painted the Kelly works on the Reeds’ dining table. She was right next to him, mixing his paints and priming the canvases. As Sunday Reed cultivated and directed Nolan’s talents, he matured and grew more confident as an artist.

The play, written by Anthony Weigh and directed by Sarah Goodes (Julia), is not a straight-up biographical retelling. Sunday will mime the stories and the myths surrounding the woman as it examines the intersection of art, power, sex and love.

“Sunday’s philosophy is it is possible to love more than one person at a time, and how that brings out different sides of you, for better or worse,” Nikki Shiels, who plays Reed in Sunday, told The Nightly.

Shiels played the role during the original Melbourne season and reprises it alongside cast members including Matt Day and James O’Connell.

For Shiels, Sunday Reed is long overdue for her moment at the centre of our national narrative. She contended that the production wants to relitigate discussions of the relationship between creation and collaboration in art, and demystify the fantasy of the genius, solo male artist, conjuring as if divined.

“As a female actor, I get very frustrated by the trope of the male artist and the muse. What I’ve been investigating in the work is activating her from muse to collaborator, which will probably upset some people. But that’s how you create drama,” Shiels argued.

“Who ultimately owns that art? She was a patron and a collaborator and he was an artist, and it was a mutually beneficial professional engagement, but, of course, it was a very naughty and complex personal relationship.

“She and John were a seminal part of creating a national artistic identity that was throwing away the cultural cringe, and was detached from Europe.”

As the saying goes, behind every powerful man is a more powerful woman, and when Sunday played in Melbourne in early 2023, audiences told Shiels they had no idea of Sunday Reed’s role in the Nolan paintings. Shiels said attendance spiked at the Heide Museum of Modern Art, which occupies the former Reed home in Victoria.

“(The play) elevates a person involved in (Nolan’s) life who is not as famous as he became, who was seminal in the making of him as a man and as an artist. Especially as she’s a woman in the early 1940s who was robust, intelligent and challenging the conservatism of the time. She’s very modern,” Shiels said.

“A lot of the things being negotiated in the play are very contemporary ideas and issues. Although it’s set in the past, it’s really surprising to Australians to be awakened to these women that were kind of written out of our own history.”

As the main character of her own story, Sunday Reed is now more than just five words on a gallery wall.