THE WASHINGTON POST: Emotional scenes in Birmingham as fans and family honour metal icon Ozzy Osbourne

A sea of mourners gathered in Birmingham to say a poignant farewell to Ozzy Osbourne, the ‘Prince of Darkness’ and hometown hero.

The headbangers threw flowers atop the black hearse, as a brass band played a cover of Iron Man.

Thousands of mourners came out to watch the funeral procession. They chanted “Ozzy!” and raised their hands in “devil’s horns” sign as his cortege rolled down Broad Street in Birmingham’s city centre.

The world last week lost Ozzy Osbourne, the front man of Black Sabbath, heavy metal founder and bat-munching TV dad. But Birmingham lost a native son, a “Brummie lad” and “working class hero” from the Aston neighbourhood, where parents toiled in the local factories as their kids learned to bang on drums and guitars.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

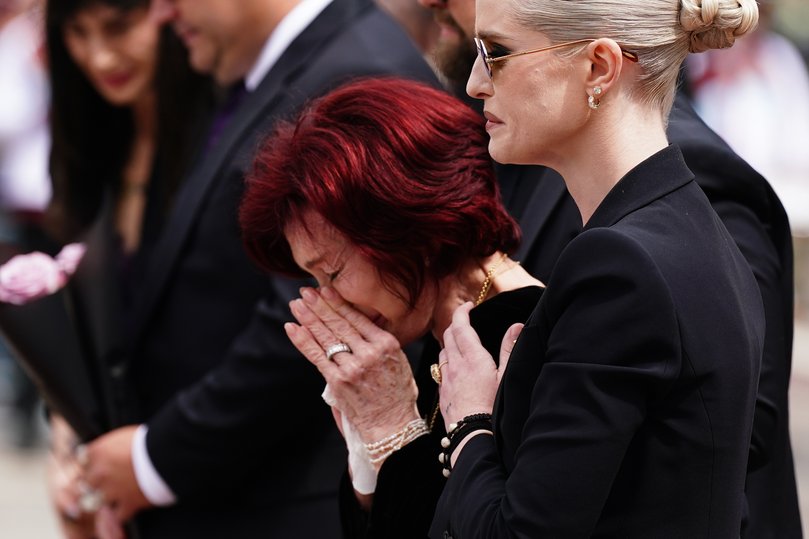

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Amid the tribute, deeply moving moments unfolded as Ozzy’s wife Sharon Osbourne and their children, Kelly and Jack, stepped forward to place roses atop the growing mound of flowers at the “Black Sabbath Bench”.

He was born John Michael Osbourne and died on July 22, at 76, of a variant of Parkinson’s disease, likely not helped much by a once-wild lifestyle of drugs and alcohol. He performed - sitting on a black throne - in a farewell concert at Birmingham’s Villa Park soccer stadium earlier this month.

Because of the Emmy-winning MTV reality show, “The Osbournes,” many Americans might remember him best as an economic migrant to Beverly Hills. But 90210 was not his forever home. He was buried Wednesday in England.

Tracey Beebee, 60, a lifelong fan from an old coal mining village north of Birmingham, wept openly. “At a time in my life when I didn’t fit - when a lot of us didn’t fit in - we had Ozzy,” Beebee said. “All the odd people didn’t feel so odd because we had Black Sabbath.”

Black Sabbath is widely credited as a foundational heavy metal band, noted for its dark, heavy, loud blues rock-influenced sound, with lyrics about doom and destruction.

“No band is more influential on heavy music than Black Sabbath, - a truism we might even extend to the idea of heavy metal thinking,” wrote the Washington Post pop music critic Chris Richards in a recent appreciation, “that is, a heightened state of youthful ennui and fomenting skepticism routinely dismissed throughout the pop culture of the ’80s and ’90s as loser juvenilia.”

In Birmingham, England’s second city, the metalheads waited quietly for the hearse to appear, with many mourners dressed in black jeans and leather vests, sporting old and new concert T-shirts, celebrating not only Black Sabbath but also their spawn, bands named Cannibal Corpse, Hell Storm and Slayer.

Though some in the crowd discretely sucked down cans of beer, it was a kid-friendly celebration for the Prince of Darkness, who liked to describe himself as “a family man.”

In interviews here, ageing thrashers pointed at Gen Z fans and nodded appreciatively.

“The young will keep the tradition alive,” said John Cooper, 69, a lifelong local Sabbath fan and retiree who spent his working life in a factory that made nuts and bolts.

His friend, Baz Drew, 53, showed off a tattoo on his left arm. It featured a fading visage of Ozzy in his younger years, but underneath he had just added the dates marking the rocker’s birth and death, “1948 to 2025.”

“He was from this place, he was this place,” Drew explained, which, in honesty, “he might have described as a slum.”

“He remained a Brummie lad,” he said. “He was humble. But he was huge.”

Drew’s friend, Chris Carpenter, 51, who works at a factory making Land Rovers, showed off his four fingers, which were also tattooed, to read “O-Z-Z-Y.”

“He was bigger than the queen, really,” Carpenter said. The mourners agreed it was a travesty that Osbourne wasn’t knighted by King Charles III, who was a fan of sorts.

The British press revealed that the two exchanged correspondence over the years. Osbourne performed at Queen Elizabeth II’s Golden Jubilee concert at Buckingham Palace in 2002, playing the Black Sabbath hit “Paranoid.”

In a less regal, if no less memorable, moment, during a solo performance in Des Moines on Jan. 20, 1982, Osbourne bit the head off of a bat. He later joked that the stunt would appear in his obituary.

At one point Wednesday, the crowd grew silent as Ozzy’s wife, Sharon Osbourne, and two of their children, Kelly and Jack, stepped out of a black car to place roses beside the mountain of flowers left on top of the “Black Sabbath Bench” next to the “Black Sabbath Bridge,” just down the road from the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, which is featuring the exhibit “Ozzy Osbourne: Working Class Hero.”

Osbourne and his band mates were from the Aston neighborhood. His dad was a toolmaker; his mum worked at an auto parts factory. The bassist for Black Sabbath, Geezer Butler, was from down the road. The Butler family’s home had been bombed by the Luftwaffe in World War II. The band’s guitarist, Tony Iommi, lost the tips of the middle and ring fingers of his right hand at his job at a sheet metal plant.

Osbourne was scheduled to be buried at a private ceremony.

The Lord Mayor of Birmingham, Zafar Iqbal, said Osbourne put Birmingham “on the map.”

“I think it was a fitting tribute to a legend who was a Brummie through and through,” Iqbal said. “Like his final gig, he came back home and we were proud to have him.”

David Winser, 20, was carrying a bouquet of red roses, with a handwritten note thanking Osbourne for all he meant to him, adding, “Heroes get remembered and legends never die.”

Winser plays guitar and has dreams, too, and a band. What’s it called? “Doesn’t have a name yet,” he said.

Along the curb, Mel Higgins, 21, a student, said her favorite Osbourne song was probably “No More Tears” from 1991, which the singer once called “a gift from God.”

Asked how long she’s been a fan, Higgins said, “Since I was a baby.”

“My dad used to play Black Sabbath records all the time,” she said, adding that she was happy to celebrate the passing star. “Because not really anybody famous is from Birmingham,” she said.

© 2025 , The Washington Post