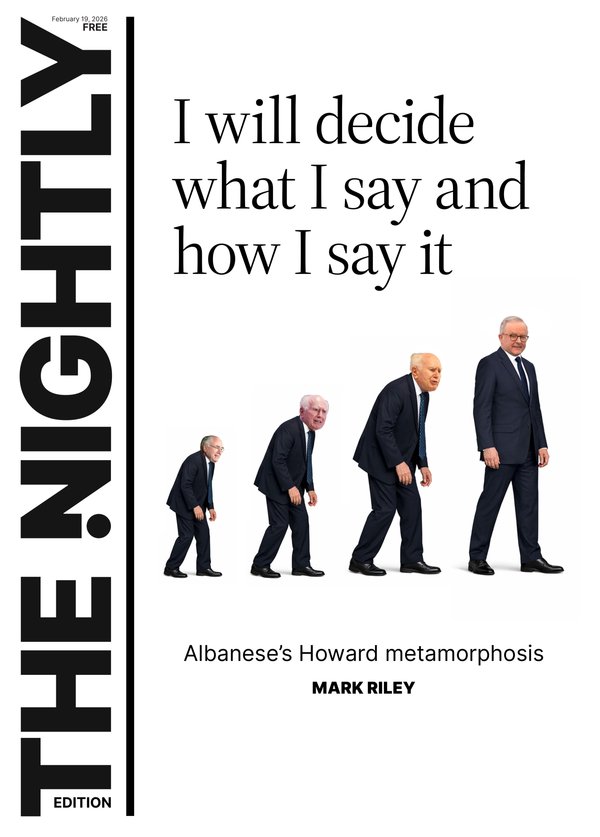

THE WASHINGTON POST: We knew ‘America’s Next Top Model’ was cruel. But we watched it anyway

Reality Check: Inside America’s Next Top Model gathers many former judges and contestants to collectively ponder the notion that perhaps some of this was not such a good idea.

Nothing has ever made me feel like more of a withered crone than trying to explain what was wrong with us in the early aughts. Why did our society think Jessica Simpson was fat? Why did we think Britney Spears’s mental health was a punch line?

Pick a starlet: Lindsay Lohan. Amanda Bynes. Janet Jackson. For a good decade, America’s response to encountering an optimistic young woman of some talent was to ruin her.

A few years ago I began seeing sweet summer children on my TikTok feed discover, in horror, that their ancestors once gathered around large televisions to warm themselves in front of America’s Next Top Model, a show in which aspiring models wore tarantulas and starved.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Sometimes these models’ dedication to high fashion required them to apply fake blood and pretend to be dead, or to apply fake vomit and pretend to be barfing, or to use real, actual homeless people as props for the purpose of selling pants that cost more than my car.

“This show is kind of problematic!” one social media user exclaimed, as if she had made a startling archaeological discovery, and yes, dear duckling, it was problematic. Which we mostly knew, but also, living on SnackWell’s and Olestra had prevented large amounts of oxygen from reaching our brains.

Anyhow, this excavation of our ancient history has led to a new Netflix docuseries, Reality Check: Inside America’s Next Top Model.

The show, which ran from 2003 to 2018, was ostensibly a reality competition for young women trying to break into the fashion industry.

They came from Pennsylvania, they came from Florida, they came from down-market beauty pageants, and middle-America Walgreens, and the Lord sent one or two innocent fawns from His suburban megachurches, all to live at the show’s Model House in New York.

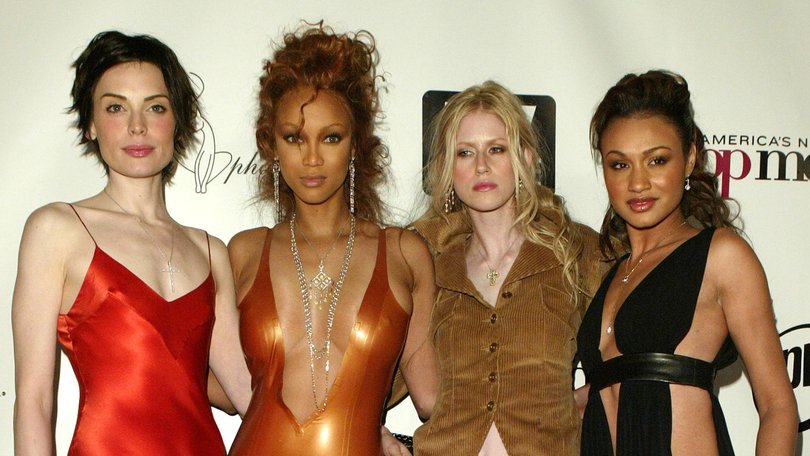

Each week, host and creator Tyra Banks dispatched her contestants to modelling-related assignments (makeovers, runway walking lessons), and set up an elaborate photo shoot.

At the end of the episode, the girls would be judged on their performance by a panel of industry professionals, who saw it as their sacred duty to inform some of the most beautiful girls in the country that they were, in fact, heifers.

A couple of the judges — photographer Nigel Barker, creative director Jay Manuel — did this with a measure of regretful solemnity. Others, like retired model Janice Dickinson, did this with glee, as if the only way to maintain her own beauty was to feed poison apples to the generation below her.

“She needs to lose 150 pounds!” she once crowed over a plus-sized model, suggesting a number that would have left the girl weighing less than a small border collie.

Reality Check: Inside America’s Next Top Model gathers many former judges and contestants to collectively ponder the notion that perhaps some of this was not such a good idea.

Maybe it wasn’t great that one contestant, Danielle, was told she would be eliminated if she didn’t agree to cosmetic dentistry to close the gap between her teeth.

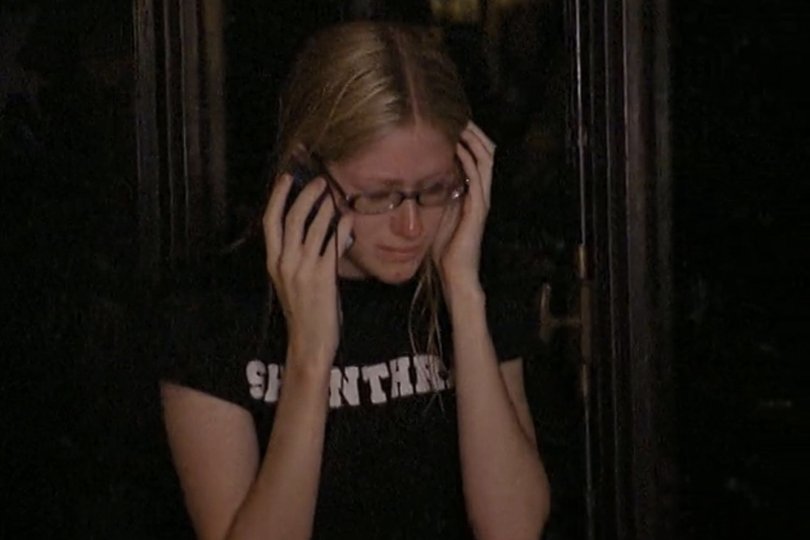

Perhaps in retrospect, cameramen should have intervened when Shandi became so blackout drunk that she appeared unable — at least to viewers — to consent to a sexual encounter in Milan.

Instead, they filmed the whole thing and forced her to call her boyfriend back home to confess the incident on-air.

On second thought, one might argue that the multiple — multiple! — challenges that required contestants to wear versions of blackface or brownface could have been skipped?

“I was feeling it,” a white girl named Brittany enthused, after wardrobe handed her an Afro wig as well as a young Black child, and we can only presume “it” was “the mortification of my soul”.

But whose fault was it? Whose fault was any of it?

The dangedest thing is that nobody in Reality Check seems to know. There’s a real “mistakes were made” quality to this docuseries. Jay Manuel repeatedly claims he was disgusted by the show’s stunts, but when asked whether he ever complained to Tyra, whom he’s described as his bestie, he immediately demurs that it wasn’t his place.

Runway coach J. Alexander presents himself as a den mother to all the poor, misbegotten models, but in archival footage he’s nearly as catty as Janice, only with better legs.

And Tyra? Who knows. She spends half the docuseries explaining how she was intimately, minutely involved in every brilliant aspect of the show, but her memory suddenly goes foggy when she’s asked about trash parts.

Shandi’s horrific experience in Milan? She didn’t know anything about that, she insists. The blackface? Her unique way of showing that all skin tones were beautiful.

The show was just a product of its times, she insists: “You guys were demanding it.”

Were we? I don’t personally recall ringing up Les Moonves to say that I wanted to see 12 young women get knocked over by swinging pendulums and wear dresses made of raw beef, but who can remember — it was a long time ago in the fog of war.

And many of us did watch it, after all, with a blend of schadenfreude and longing. A friend of mine told me the other day that the show “robbed her of her hot years.”

ANTM’s peak coincided with her time as a lovely 5-foot-9 teenager, but because she weighed more than the 115-pound models on the screen, she couldn’t see that she was actually gorgeous.

I was a 5-foot-4 gremlin in no danger of comparing myself to the models, but in retrospect maybe that’s why I enjoyed watching them topple over in their stilettos and slaughter the words on a teleprompter.

These days, I wouldn’t be taken in by America’s Next Top Model. But I am enthralled by figuring out what enthralled us 20 years ago.

What made it acceptable to be entertained by the contestants’ misery? What made viewers feel free to sit on their sofas eating bags of Funyuns, wiping fingers on a Snuggie while expertly declaring that Caridee had a short neck?

In recent years, documentary after documentary have been preoccupied by this period of American popular culture, analysing how depraved it was, how mean and casually mocking.

Fit for TV: The Reality Of The Biggest Loser explored how the popular weight-loss series wasn’t inspirational, it was cruel. The Dark Side Of Reality TV, took on a different early-aughts hit — The Swan, Toddlers & Tiaras — with every episode.

Multiple documentaries about Britney Spears explored how obsession with her teenage sexuality wasn’t fun, it was creepy. Pamela, a Love Story, explained what should have been the very basic premise that watching Pamela Anderson’s sex tape was actually just a gross violation of privacy.

What makes each of these productions interesting to me is that I’m not sure any of them needed to be made. A good documentary helps you understand something you didn’t previously understand.

But if you watch an old episode of The Biggest Loser now — trainers screaming at contestants while they collapse on treadmills and subsist on the caloric intake of a toddler - we already intrinsically know that it’s bad. We don’t need a modern voice-over contextualising it; we can see it with our own eyes.

These documentaries are not a learning tool, they are a penance. They are an apology to our former selves, for all the things we did so badly 20 years ago.

In “Reality Check,” former contestant after former contestant takes the screen to talk about how the show damaged her career potential.

They would show up at go-sees with their ANTM portfolios and be turned away at the door — casting directors were looking for clean, competent catalogue work, and instead they were arriving with photographs of bejewelled Madagascar cockroaches crawling all over their bodies.

The top models went back to their Walgreens jobs. The biggest losers regained the weight. The women of The Swan found that plastic surgery increased, rather than solved their depression. It turns out we shouldn’t have toddlers wearing tiaras.

Ruin her. What a time to have watched television. Our most popular shows promised the opportunity of a lifetime, but it turned out they were just beautiful wrecking balls.

© 2026 , The Washington Post