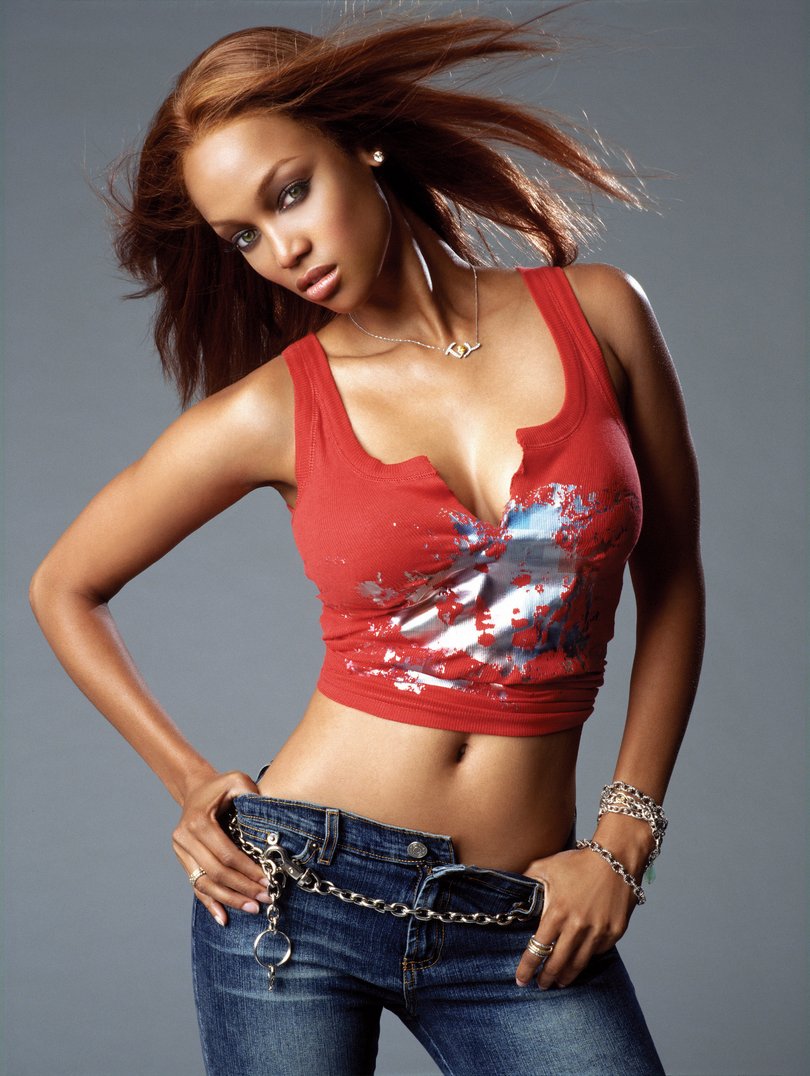

Reality Check: Inside America’s Next Top Model docuseries relitigates Tyra Banks’ toxic TV series

From an alleged sexual assault caught on camera to accusations of fat-shaming, racism and misogyny, America’s Next Top Model had it all.

Every episode of America’s Next Top Model asked, “You wanna be on top?”, Across the show’s 24 seasons, it crowned 24 winners, but the only real victors of the reality TV competition were the producers and the TV network.

At the peak of its power, America’s Next Top Model was watched by more than 100 million viewers in 170 countries, and spawned 50 international versions including an Australian one. For a show that was rejected by all the major American networks, and picked up by a broadcaster that was frequently the lowest-rated, it was decidedly on top.

It magnetised audiences with its melodrama and stunts, always going to further extremes as a bulwark against the likes of Survivor and Fear Factor. You could almost forget what its original raison d’etre was, or purportedly was.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.The show ran for 15 years and made an even bigger superstar out of Tyra Banks, who conceived of a series that went behind the scenes of what it takes to shape a model, and pitched with producer Ken Mok as a cross between The Real World and American Idol.

So, how did a series that went from, according to Banks, one that was supposed to be more inclusive and showcase a wider definition of “beauty” to one whose legacy has been toxified, wrapped up in accusations of body shaming, exploitation and racism?

That’s the thesis at the centre of the three-part docuseries Reality Check: Inside America’s Next Top Model, which is streaming from tonight on Netflix.

It features interviews with Banks, Mok, and her coterie of onscreen sidekicks creative director Jay Manuel, photographer Nigel Barker, and runway coach J. Alexander, plus former contestants Shannon Stewart, Shandi Sullivan, Ebony Haith, Giselle Samson, Danielle Evans and Whitney Thompson.

When Banks launched ANTM in 2003, she had been an industry icon, someone who pushed through the barriers to become the first black woman to appear on the covers of Sports Illustrated and GQ. Doors had been closed to her, and she wanted to open them and leave them open for the women behind her.

“I had a feeling I was going to change the beauty world, this was my way to get back,” she told the docuseries.

That’s where it started, that’s not where it went. Despite the commitment to casting more diversely, including body types (an Australian size 10 was considered “plus-size” on the show), the series ended up reinforcing the elitism and exclusivity of the beauty and fashion industry.

Former model Janice Dickinson was a judge in the early seasons and almost everything she said about the contestants were either deeply offensive or, at the very least, blithely petty. She was particularly generous with body-shaming.

But it was Banks’ judgement and choices that seemed to hurt the contestants the most.

Each season had between 10 and 16 candidates, and some of them came from vulnerable or marginalised backgrounds. The show was a way out of a tough situation, a ticket to opportunities.

One of them was Danielle Evans, the eventual winner of the sixth season. Hailing from Little Rock, Arkansas, she was persuaded to try out when her brother pointed out that there was no other way she would be able to afford to go to New York City.

So when she given the “option” of either having the gap in the tooth closed despite her vehement protestations, or leave the competition, there was only one choice, as heartbreaking as it was. She wasn’t going to go home.

There was Ebony Haith, from the first season, a black woman from Harlem. Because of Banks’ involvement, Haith said she thought she would be protected on the show, that she had a kindred spirit in someone who understood the discrimination she would face.

It wasn’t to be. The judges, including Banks, used words such as “aggressive”, “angry” and “difficult to work with”, coded language that has a different resonance for a black woman.

Haith was also criticised for her skin. During a judging panel, Banks said that she’d been told Haith that “your skin texture should be like butter, at the retouching session, your photo was the hardest to do”.

Haith recalled, “I remember thinking I had so much I wanted to say, but I had to be still”.

That was the thing that many of the former contestants who sat down for the docuseries expressed, their personal disappointment in Banks who could come across as a den-mother and mentor, but then turn on them for the sake of good TV.

That was starkly evident in one of the show’s worst moments. It was the show’s second season and with an increased budget, the first time it took the circus overseas. After a long day in Milan, the production had invited some male actors who had earlier been part of the day to the house where the girls were staying.

What you saw on TV was Sullivan partying, drinking and getting into a compromising position with a male actor in the hot tub. The two then later go into the shower together and appear to have had sex.

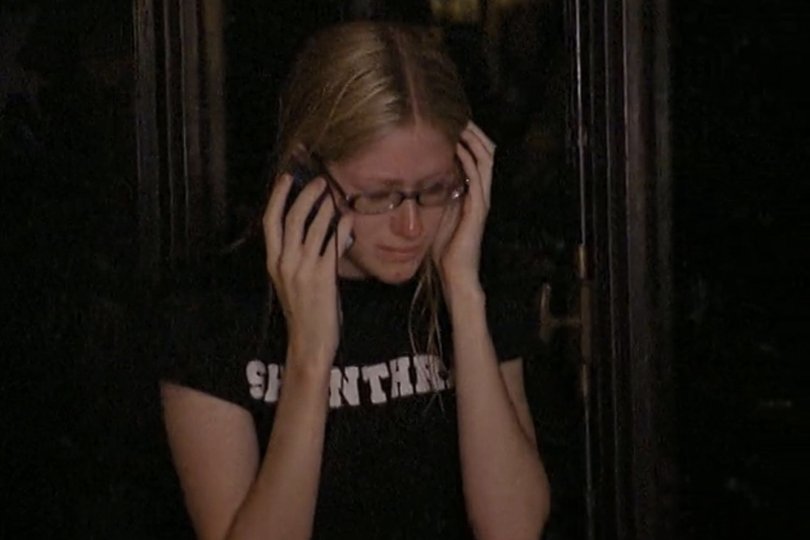

The next day, Sullivan is show having an emotional meltdown at the fact she cheated on her boyfriend, whom she confesses in a tear-soaked phone call.

What really happened was Sullivan, by the time she had climbed into the hot tub, was already two bottles of wine deep.

“I was pretty drunk at that point. Everything kind of after that is just a blur,” she recalled to the documentary. “I remember him on top of me. I was blacked out. No one did anything to stop it, and it all got filmed. All of it.”

She said she didn’t even “feel sex happening, I just knew it was happening, and then I passed out”.

The production crew had visibility over the event the whole time, and no one stopped it. In the aftermath, when Sullivan asked producers for a phone to call her boyfriend, they said that was fine, but it would all be filmed.

The resulting scene is Sullivan, deeply distressed and prostrate on the ground, begging for forgiveness between heaving sobs, while her boyfriend, whose audio was recorded, called her a “stupid b-tch”. Sullivan recalled that the sound technician and the cameraman in the room with her apologised to her.

She was also filmed calling the male actor to ask if he used protection or if he had STIs, rather than just have the production facilitate and ask those questions of him off-camera, and a camera crew followed her to the doctor to have her checked up. It was all framed as good TV.

There is an argument that in 2004, our understanding of sexual assault and consent were much murkier, and it’s one thing to say that now, more than two decades later, we all recognise what allegedly really happened that night (Sullivan was forthright when she said it was sexual assault”), but even then, even watching the footage as viewers, it wasn’t right.

It certainly wasn’t right when Banks, rocking up the next day in a scene, led the assembled girls including Sullivan in a discussion around infidelity and “fighting against their carnal desires”, designed to guilt trip and make her squirm on camera. The episode was titled, “The Girl Who Cheated”.

Confronted with that now, Banks told the Reality Check filmmakers that she wasn’t involved with how it was handled and that she wasn’t involved with the “production” side.

Mok said that they treated the show “as a documentary” and the girls had all been warned they would be filmed all the time. The rule was that if you went into the bathroom alone, it would not be recorded, but if you went in with someone else, it was fair game.

He added, “For good or bad, it’s one of the most memorable moments in Top Model”.

With 24 seasons of TV, ANTM had a full run sheet of controversies and scandals, including unhinged concepts for photo shoots.

There was the one where they had to act out model stereotypes, and featured one girl posing on the toilet covered in fake vomit to illustrate “bulimia”, another shoot in which they posed as crime scene photos. One contestant, Dionne Walters, was given the assignment of being photographed as if she had been shot in the head.

Walters said production knew her mother had been shot years earlier and was now paralysed from the injury, and she suspected that had given her that particular look to trigger an on-camera breakdown. Mok said he took responsibility for the poor judgment of this concept.

There were the photoshoots where they wore animal carcasses as clothes, or when they were suspended several storeys in the air, or pretended to be homeless, with real-life unhoused people in the background.

One of the most jawdropping – and memorable – was the 2004 race swap shoot, where the contestants donned black face, brown face and yellow face.

Banks said, “I didn’t think it was controversial, I was in my little bubble, in my little head and this was my way of showing the world that brown and black is beautiful” but now conceded that through a modern lens, she “now understands 100 per cent why (it was an issue).

The show repeated that challenge in 2009.

When the pandemic hit, ANTM found a resurgence among audiences with too much time to fill, and a younger generation discovered its lurid dramas. But they were appalled at what they saw.

Sure, it’s easier now judge a show that was part of an overall toxic culture of the 2000s that was particularly hard on young women thanks to the hangover of the heroin-chic 1990s, and the burgeoning power of tabloid media and internet blogs coupled with centuries-old misogyny and racism.

The core group of creatives including Banks, Mok and, to a lesser extent Manuel, Alexander and Barker, are now variously contrite and evasive over some of what happened on screen and behind the scenes (“It wasn’t my place” was a phrase or sentiment heard more than once).

Banks is the face of the show so has copped the most blame, but there were a lot of complicit people.

But America’s Next Top Model wasn’t just a symptom of the culture, it also reinforced some of the worst aspects of it, and caused real harm to the people involved.

Let’s hope there’s never a season 25.

Reality Check: Inside America’s Next Top Model is streaming in Netflix from 7pm AEDT on February 16