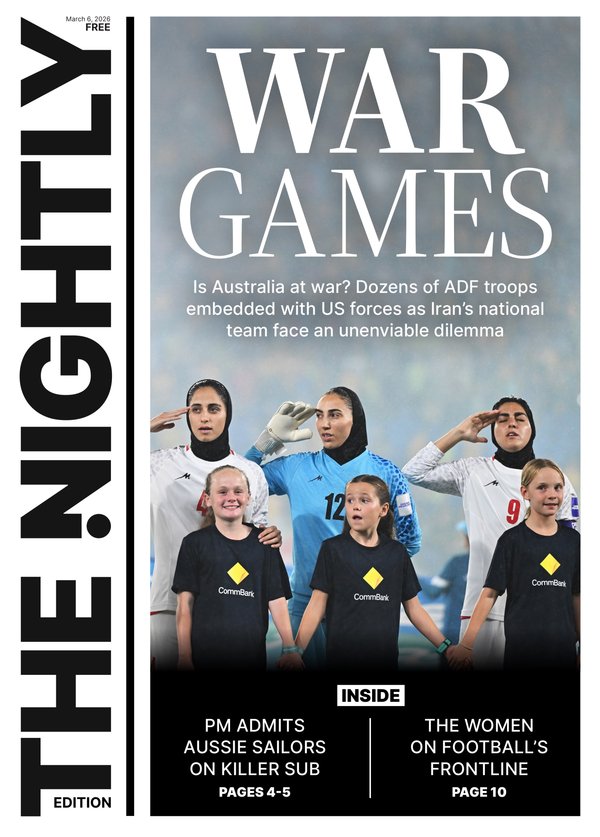

What “Wuthering Heights” says about Hollywood’s reboot obsession

Elizabeth and Darcy and Cathy and Heathcliff are just as meaningful to many people as Batman and Superman

Emerald Fennell is very much aware that her adaptation of Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights is going to piss off Bronte purists.

In fact, the title of the movie is technically “Wuthering Heights” - quotation marks and all - to denote that this is something different.

The director ditches major characters and changes many plot points.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Charli XCX songs dominate the soundtrack, and costumes look like they came from a deranged child’s dollhouse. Perhaps the biggest difference between Fennell’s and the original is that, in the new version, Cathy (Margot Robbie, also a producer) and Heathcliff (Jacob Elordi) consummate their forbidden love. A lot.

They have torrid sex. He licks her face and sucks her fingers.

At the same time, “Wuthering Heights” is still Wuthering Heights, and the latest is an example of one of Hollywood’s favorite hobbies: adapting classic novels about women in the 19th century over and over.

It’s the reboot culture that’s consumed the mainstream studios, but with a twist. Whereas superhero stories are largely aimed at men, these appeal to a distinctly female fan base.

Fennell’s film remains a story about Catherine Earnshaw, who’s obsessed with Heathcliff, the “gypsy” boy her father brought home as an orphan. Cathy and Heathcliff still become childhood friends, and she still marries the wealthy Edgar Linton.

She and Heathcliff still continue to pine for one another and ruin each other’s lives.

In that, Warner Bros’ “Wuthering Heights” isn’t all that different from the many, many filmed versions of Bronte’s 1847 novel, including the 1939 incarnation with Laurence Olivier and the particularly grimy one in 2011 by acclaimed British auteur Andrea Arnold.

“There is a sense of going back to the well again and again for material that is really about women and for women or for female audiences,” says Katja Lindskog, a professor at Yale University who specializes in Victorian studies and teaches a course on the “aesthetics of adaptation.”

And Fennell’s “Wuthering Heights” isn’t the only literary reboot we’ll be getting this year.

In September, Focus Features will release a new take on Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility, starring Daisy Edgar-Jones. Netflix is at work on another series recounting the narrative of Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, this one with The Crown’s Emma Corrin in the coveted role of the feisty Elizabeth Bennet and Slow Horses’ Jack Lowden playing the buttoned-up Mr Darcy.

It seems a daunting task to remake that novel. It was immortalised in a 1995 BBC miniseries that made viewers weak in the knees for Colin Firth.

Then came a 2005 movie starring Keira Knightley, which was so well loved that when it was re-released in theatres last year, it made more than $US6m ($8.5m) domestically, over 16 per cent of the original domestic box-office haul.

But the streamer has deemed it worth the risk. Why?

For one, Netflix’s Bridgerton, based on a series of novels by Julia Quinn, has made it clear that audiences are eager for sexy trysts involving empire-waisted gowns with a dose of pop sensibility.

The first episode of the fourth season, which premiered at the end of last month, was watched by 6.4m US households in the first four days of its release, according to TheWrap.

Without the BBC Pride and Prejudice, there would probably be no Bridgerton. The newer series proved there’s a 2020s interest in that kind of material. To capitalise on that, why not just go back to the original?

In 2022, Netflix distributed a Dakota Johnson-starring version of Austen’s Persuasion that seemed made for the algorithm, with heroine Anne Elliot delivering asides to the camera like she was in Fleabag. Critics hated it, but it has a 72 per cent audience score on Rotten Tomatoes.

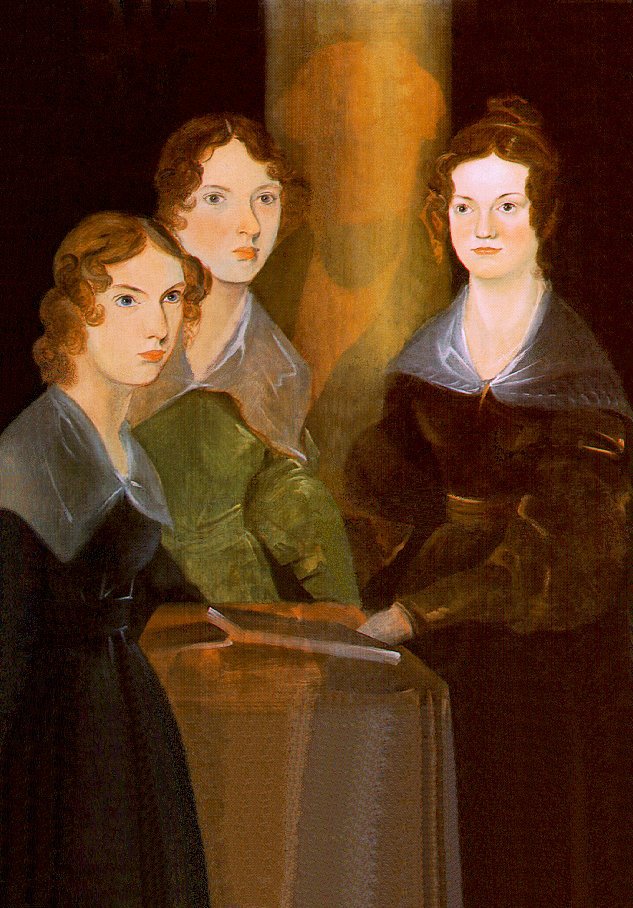

It’s not quite accurate to lump the works of Bronte, her sisters Charlotte and Anne, and Austen together, but in the world of entertainment, they bleed into one another as costume dramas focused on the passions of women. Sure, Austen’s works are from Britain’s Regency era and often feature hyper-articulate heroines who talk through their feelings. Emily and her sisters’ Victorian novels bristle with the threat of violence.

But they all include brooding men and societal pressure to marry. And it’s likely that women will respond to these sagas.

“Women are conventionally seen as loyal readers, and as loyal groups that really kind of cluster around certain ideas or stories, particularly marriage plots, again and again,” says Yale’s Ms Lindskog. “Almost no matter what generation, there’s a hunger for it.”

These days, intellectual property rules Hollywood.

With a few notable exceptions, such as Sinners, original ideas struggle at the box office. Books like Wuthering Heights may be more than a century old, but they remain reliable pieces of IP. From there, modern artists can Trojan-horse modern political themes about class and female desire into their versions.

“There’s also a sense in which these stories are not overtly political, and they are not overtly even feminist,” Ms Lindskog says. “They are not overtly any of these things that might be seen as potentially off-putting, but they let us talk about all of those things.”

In fact, while studios don’t have to worry about offending anyone by investing in a re-imagining of a classic, the subject matter might feel more relevant than ever. The production design allows for a form of cosplay, while the topics of repression in women’s lives are all too familiar.

But there’s also a more wholesome reason these adaptations keep popping up: The books are just that good.

“They are such immortal and gripping stories that the Brontes wrote. If you’ve read them and you love them, it’s no surprise that they’ve got that timeless hold on everyone’s imagination,” says Brontë expert Sharon Wright, co-author of Let Me In: The Brontes in Bricks and Mortar, with Ann Dinsdale.

“Really, everyone keeps returning to them because they are addictive.”

Fennell has just taken the ownership these fans feel and turned it into an extravaganza with an estimated $80 million budget per Deadline.

She’s also been extremely open about her “Wuthering Heights” not being a strict adaptation of the book but an adaptation of the way she interpreted it when she first read it at 14. In a forward she wrote for a new edition of the novel, Fennell explains that “adapting Wuthering Heights in any literal way feels more or less impossible,” continuing, “it is too slippery, too wild, too good to distill into two hours of film.”

Watching “Wuthering Heights” you get the strong sense that Fennell is basically creating fan fiction.

Instead of keeping Cathy and Heathcliff apart, she smushes them together like two dolls. This sense is heightened by the fact that Robbie’s most famous role to date is playing a literal Barbie in Barbie.

Fennell essentially ignores a lot of the knotty themes around class embedded in Bronte’s narrative to lean into the dangerous sexiness of the story. If you love the book, the movie can be frustrating, but it works best if you try to put the text out of your brain and just enjoy the pleasures of the towering Elordi lifting Robbie with one hand by her corset.

Even if you don’t exactly like where Fennell takes the material, it’s hard to argue it’s not savvy.

Elizabeth and Darcy and Cathy and Heathcliff are just as meaningful to many people as Batman and Superman.

And female audiences can be an underserved and potent audience. Look no further than the phenomenon of the steamy, gay hockey romance Heated Rivalry. Reading Wuthering Heights is a more challenging task than reading Rachel Reid’s hockey romance novels that inspired the HBO Max series, but on screen the effect isn’t that dissimilar.

That might be frustrating for English literature scholars, but it’s good for entertainment executives looking for the next hot property. And even Bronte obsessives don’t really have a reason to be mad.

“The world’s on fire with everything that’s happening, and we’ve sat talking about Wuthering Heights,” Wright says.

“I think it’s all for the good, really.”