You’re playing Monopoly wrong: The popular board game was meant to be a cautionary tale against capitalism

Everything you thought you knew was a lie.

For something that’s meant to be a lark, every game of Monopoly ends with an obnoxiously competitive cousin or sibling ruining it for everyone.

They argue over which rules to play by, gobble up all the properties, make you pay through the roof if you land on anything, forking over rent for four houses and a hotel. Two rolls of the dice and you’re bankrupt. You have lost at the game of life.

As you stew bitterly over how you wasted three hours on a game that made all except one feel like sore losers, you start to wonder, was Monopoly meant to be a satire? Surely this isn’t meant to be a guidebook for success?

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Take away the part where you’re playing Monopoly and it actually starts to feel like real life.

The official narrative of the origins of Monopoly is that it was invented in the post-Depression era by an unemployed man named Charles Darrow, who then sold it to the Parker Brothers and was eventually rewarded millions for his ingenuity.

That is a feel-good story of American opportunity.

The true story is more akin to the reality of the viciousness of American greed and commerce, of the little guy being exploited by those who control the wealth. That Monopoly had its origins as an anti-capitalist parable that warned against monopolistic moguls was the cruellest of ironies.

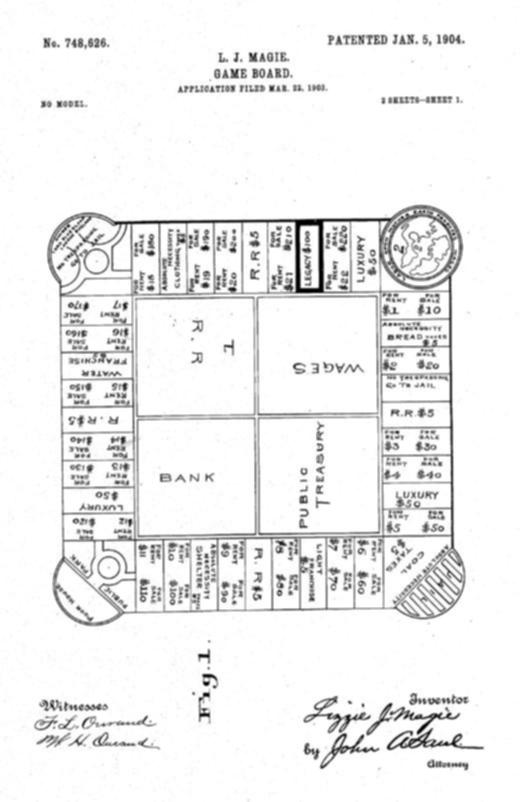

Monopoly started life at the beginning of the 20th century as an invention of Elizabeth Magie, a feminist who was descended from Scottish immigrants. She was unmarried and, unusually for the time, she supported herself financially through her job as a stenographer and secretary.

A poet and writer, Magie created the Landlord’s Game based on the economic principles of 19th-century writer and journalist Henry George who had argued that individuals should own what they create but that natural resources such as land should be shared by the people.

In a nutshell, George believed that for a more just society, tax should only be levelled on land, shifting the tax burden on wealthy landowners.

To that end, Magie created two sets of rules for her game. One in which the rewards flowed when wealth was created and shared, and another in which the eventual winner emerged victorious when they gazumped their opponents and created monopolies.

The monopolist version was meant to be a cautionary tale and a criticism of American industry titans at the time including J.D. Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie.

When the Parker Brothers later added the character of Mr. Monopoly, whose name is Miburn Pennybags, it was modelled after banker J.P. Morgan — that was clearly not in the spirit of Magie’s intention.

In a 1902 interview, Magie described her game as “a practical demonstration of the present system of land-grabbing with all of its usual outcomes and consequences”.

“It might well have been called the Game of Life, as it contains all the elements of success and failure in the real world, and the object is the same as the human race, in general, seem to have, ie. the accumulation of wealth.”

For three decades, Magie’s game made the rounds through intellectual and progressive circles. In the patent she filed in 1903, there was the “go to jail” corner, a poor house tile, and four railroad rectangles. When you passed what would eventually become the Go space, you collected $100 in wages for your labour.

It wasn’t a game that was boxed and sold through shops, rather it was passed through friends, who drew their own versions. One of those people was Darrow, who was introduced to it in 1932, and then sold a version of it to Parker Brothers.

When it emerged that Magie had the original patent, the company bought her out for $500 and there would be no royalties. By 1936, she was angry that she had been cut out of not just the riches but also of its history.

By the time Magie died in 1948, her connection to it had been swept under and her obituary made no mention of it.

In 1973, a man named Ralph Anspach was defending a lawsuit from Parker Brothers who had gone after him for his anti-Monopoly game.

During his research, Anspach came across Magie’s story and her contribution to Monopoly’s creation, and he ensured the truth entered the public narrative, which was later expanded in the 2015 book The Monopolists: Obsession, Fury and the Scandal Behind the World’s Favourite Board Game by Mary Pilon.

Today, undoubtedly the way to win Monopoly is to amass all the wealth. And you can’t win until you bankrupt everyone else. It’s a zero-sum game and it’s the distillation of the worst impulses and excesses of late-stage capitalism, Magie probably would argue if she was still alive.

What would this feminist make of the countless branded versions (Star Wars! The Beatles! Hello Kitty!), and the Cheaters edition or the annual tie-up with McDonald’s, the world’s largest fast food chain?

By 2015, according to the US Library of Congress, 275 million copies of the game had been sold.

Margot Robbie’s production company is making a movie based on Monopoly — will it be an eviscerating dissection of a rigged system, a la The Big Short, or will it be a frothy romp? You can guess what Magie would’ve wanted.

Remember, it’s all fun and games until you’re bankrupt and sent to the poor house of life.