THE ECONOMIST: The UFC, Dana White and the rise of bloodsport entertainment

There is more to the mixed-marital-arts impresario than his friendship with Donald Trump and his inclusion in the Meta board

“You look thicker” sounds like a slight. Coming from Joe Rogan, the thick-set podcasting megastar and martial artist, it is high praise.

Directed at Mark Zuckerberg, the uber-nerd behind Meta’s $1.5 trillion social-media empire, it may seem highly misplaced.

But it is true. Mr Zuckerberg does look beefier than five years ago.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.During the COVID-19 pandemic he got into Brazilian jiu-jitsu, a rough combat sport. Now he would like to see more “masculine energy” in the corporate world, too.

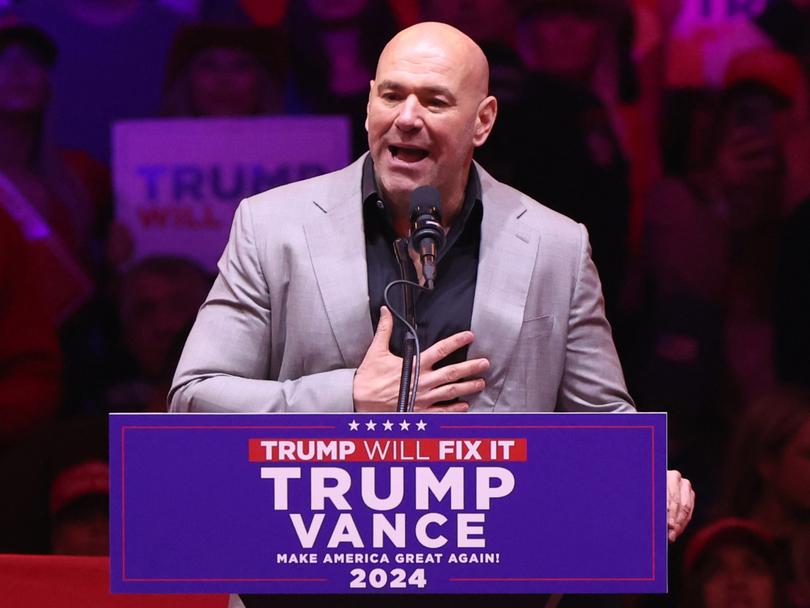

A few days before he sat down with Mr Rogan, Mr Zuckerberg invited Dana White, chief executive of the Ultimate Fighting Championship, to Meta’s board.

No other big sport league reeks more of testosterone than the UFC, in which fighters square off in an eight-sided ring, (almost) no holds barred.

Few American business figures ooze in-your-face masculinity more than the bald, bulky and brash Mr White.

And not even Elon Musk is as close to America’s alpha-male-in-chief.

Some observers point to Mr White’s decades-long friendship with Donald Trump as proof that Mr Zuckerberg’s newly thick neck conceals a weak spine.

Meta has been the target of Trumpian ire since it banned the former president from Facebook and Instagram after his bogus claims of a stolen election led his followers to sack the Capitol four years ago.

Having someone with a direct line to the White House, where Mr Trump will be moving back in on January 20, is therefore mightily convenient.

This no doubt occurred to Mr Zuckerberg.

Yet making Mr White’s elevation at Meta out to be purely about toadying is to give neither man his due.

Whatever you think of his neck or spine, Mr Zuckerberg has a head for commerce.

He rightly sees in the UFC a growth business — and in Mr White a canny businessman.

A Boston street brawler and amateur boxer turned gym operator in Las Vegas, Mr White became enamoured with mixed martial arts some 30 years ago.

At the time the multi-discipline sport was being banned in many American states and banished from big arenas.

By the late 1990s some fights were held in the car parks of third-rate gambling parlours in places like Mississippi.

Mr White spied an opportunity and in 2001 persuaded Lorenzo and Frank Fertitta, childhood friends who ran a successful casino business, to help him buy the struggling UFC for $2m.

At first red ink flowed as profusely as blood from fighters’ noses.

But the trio stanched the losses, cleaned up the sport and gradually won over mainstream audiences.

In 2016 they sold it for around $4b to a consortium led by Endeavor, a talent and sports-marketing powerhouse.

Even adding the $50m or so that the Fertittas chipped in to cover initial losses and to bankroll “The Ultimate Fighter”, a reality-TV show now in its 32nd season which helped humanise what critics had disparaged as “human cockfighting”, this translates to an average compound annual return of over 40 per cent.

Not quite what Mr Zuckerberg made Facebook’s early backers, but tidy by most other measures.

In 2023 Endeavor and WWE, a pantomime wrestling franchise now streaming on Netflix, combined their assets into a publicly traded company, TKO Group.

Since then the UFC has earned its listed parent $1.3b in revenue and $770m in gross operating profit and helped nearly double its market value to $24b over the past year.

Some 700m people in 170 countries are fans.

They are young, mostly male, with a median age in America of 37, compared with 39 for the NBA (basketball), 41 for NASCAR (motor racing) and 46 for the NFL (American football).

Nearly half are aged 18 to 34, the knock-out demographic group for advertisers.

Analysts expect an almighty bidding brawl when the UFC’s broadcasting rights come up for renewal in the next few months.

With no other big rights up for sale until 2028, these could fetch more than $1b a year, double its current deal with Disney’s ESPN sports network.

Sales of tickets to live fights and money from sponsorship deals, including with Monster Energy drinks, Bud Light beer and Timex watches, are up.

The UFC might not be where it is without Mr White.

He is no teddy bear.

Last year TKO reached a $375m settlement with ex-fighters alleging the UFC suppressed their pay.

In 2022 a video surfaced of him slapping his wife.

His mother has called him a “tyrant”.

But as a businessman, he displays two important talents.

The first is his ability to spot trends.

He filled a gap in the market for controlled aggression left by a disarray in the world of boxing.

The UFC has fewer rules but more sway than that more genteel sport’s disparate federations.

It is commissioner, owner and promoter all in one, says Mark Shapiro, TKO’s president.

Mr White was also early to grasp the power of reality-TV and social media to paint fuller pictures of the fighters outside the ring, and of streaming to bring it all to audiences.

This, plus clever match-ups, makes him “a mastermind of unscripted drama”, says Gareth Balch of Two Circles, a sports-marketing agency. Ampere Analysis, a research firm, reckons 61 per cent of UFC fans would pay to watch it, better than NASCAR (44 per cent) and not far off the NFL (65 per cent).

A White knuckle ride

Mr White’s other trait is pragmatism.

Despite his ties to Mr Trump and the UFC’s association with a right-wing bro culture, he is no MAGA warrior.

In 2016 he helped persuade Democratic state lawmakers and the governor in New York to legalise the UFC there.

He rubs along with Ari Emanuel, CEO of TKO Group and brother of Barack Obama’s White House chief of staff.

After the American right boycotted Bud Light over an ad featuring a transgender influencer in 2023, while Mr White was cutting a deal with its owner, AB InBev, he successfully pressed Mr Trump and his acolytes to uncancel the brand.

As one of the world’s top ad men, Mr Zuckerberg would recognise this as a marketing coup for the annals.

Originally published as The UFC, Dana White and the rise of bloodsport entertainment