THE NEW YORK TIMES: Iran’s Dilemma — How to preserve its proxies and avoid full-scale war

Israel’s war against Hezbollah in southern Lebanon is another embarrassment for Iran and its new president, raising the pressure on him to strike back at Israel to defend an important ally.

Israel’s war against Hezbollah in southern Lebanon is another embarrassment for Iran and its new president, raising the pressure on him to strike back at Israel to defend an important ally.

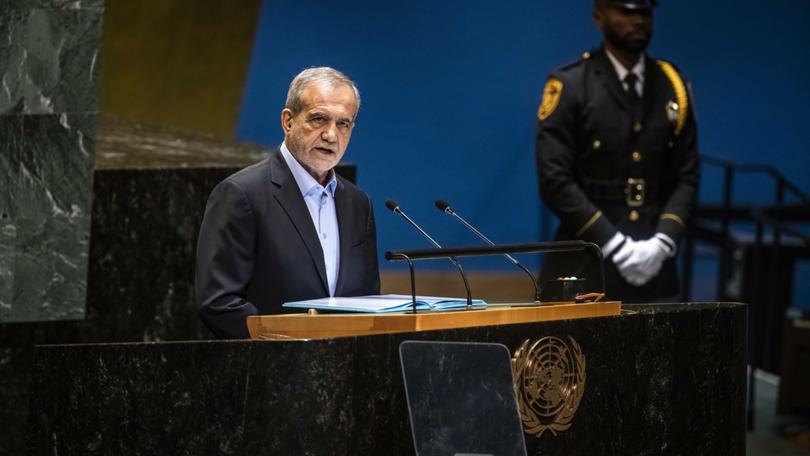

Iran has so far refused to be goaded by Israel into a larger regional war that its supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, clearly does not want, analysts say. Instead, President Masoud Pezeshkian is at the United Nations hoping to present a more moderate face to the world and meeting European diplomats in the hopes of restarting talks on Iran’s nuclear program that could lead to vital sanctions relief for its hobbled economy.

In New York this week, Pezeshkian was blunt. Israel was seeking to trap his country into a wider war, he said. “It is Israel that seeks to create this all-out conflict,” he said. “They are dragging us to a point where we do not wish to go.”

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.After a series of humiliations, heightened by Israel’s intensified attacks on Hezbollah, Iran faces clear dilemmas.

It wants to restore deterrence against Israel while avoiding a full-scale war between the two countries that could draw in the United States and, in combination, destroy the Islamic Republic at home.

It wants to preserve the proxies that provide what it calls forward defense against Israel — Hezbollah, Hamas and the Houthis in Yemen — without going into battle on their behalf.

And it wants to try to get some of the punishing economic sanctions against it lifted by renewing nuclear negotiations with the West while preserving its close military and trade relationships with Washington’s prime adversaries, Russia and China.

“The fundamentals have not changed for Iran,” said Ali Vaez, director of the Iran Project at the International Crisis Group. “Iran absolutely does not want to get into a larger war in the region,” he said. This, he added, was likely to be one reason that Iran had so far not retaliated for the assassination of Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh while he was in Iran to attend Pezeshkian’s inauguration.

Since the overthrow of the shah in 1979 and the installation of the Islamic Republic, Iran has tried to spread its influence throughout the region and has vowed to destroy Israel. It has built a network of proxies that it finances, arms and supports but does not entirely control — Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank; the Houthis in Yemen; Shia Muslims in Iraq and Alawites in Syria; and Hezbollah in southern Lebanon, believed to be equipped with upward of 150,000 missiles and rockets, with the ability to hit all of Israel.

The Hamas attack on Israel nearly a year ago has brought the role of Iran front and center. And Israel has seized an opportunity to destroy or diminish two Iranian proxies: Hamas on its southern border and Hezbollah to its north, which has sent rockets into Israel in support of Hamas, driving thousands of Israelis from their homes.

At the same time, Israel has continued a more secret war against Iran, killing senior officers in a missile attack on the Iranian consulate in Damascus, Syria, in April. Israel and Iran then exchanged strikes on each other’s territory, before pulling back.

More recently, Israel caused panic in Lebanon with exploding pagers and walkie-talkies, displaying its infiltration of Hezbollah’s structure. It followed with a barrage of missiles and bombs that on Monday killed hundreds of people in Lebanon, in the deadliest day since the country’s civil war, which ended in 1990.

“Israel is trying to bait Hezbollah into an attack that would produce a full-fledged war and enable Israel to take the fight to what it considers its real strategic threat, Iran itself,” said Suzanne Maloney, an Iran expert and director of the foreign policy program at the Brookings Institution.

Hezbollah, too, is “disinclined to engage in a conflict that is likely to lead to its own destruction,” Maloney said. For Iran, “Hezbollah is the great deterrent — its capabilities and proximity to Israel are the first line of defense for the Islamic Republic, and if it is destroyed, it leaves the Iranians significantly more vulnerable.”

The proxies represent Iran’s strategy of forward defense, to protect the Iranian homeland. The proxies are supposed to fight for Iran, Vaez said: “It was never the principle that Iran would fight in their defense.”

For now, Iran is watching carefully, while also assuming that the well-armed and well-organized Hezbollah can stand up for itself and inflict serious damage on Israel without overt Iranian help.

Israel appears to be taking advantage of Iran’s challenges, but as ever, the risk is that it may misjudge.

There are hard-line elements in Iran’s Revolutionary Guard and within Hezbollah “who see confrontation with Israel as inevitable and would prefer it to be sooner,” said Ellie Geranmayeh, an Iran expert with European Council on Foreign Relations.

Iran must shore up its axis of resistance somehow, said Cornelius Adebahr, who studies Iran for Carnegie Europe. “Iran can’t swallow this forever,” he said. “People will ask, ‘What kind of power are you if you cannot protect your proxies?’”

In a short speech Tuesday to the United Nations, Pezeshkian accused Israel of barbarism and referred to Iran’s proxies as freedom fighters. But he also spoke of “a new era” and vowed to play “a constructive role.” Iran was ready to reengage with the West on the nuclear issue, he said.

Pezeshkian is seen as a moderate in the Iranian system. And his victory in this year’s presidential election is considered a sign that Khamenei wants to reduce the tensions inside Iran that exploded in 2022 and were exacerbated by the more hard-line Ebrahim Raisi, who was considered a possible successor to the supreme leader but died in a helicopter crash.

Accompanied at the U.N. by experienced negotiators well known to the West, Pezeshkian is trying to present his government as moderate, pragmatic and open to diplomacy.

But the timing is complicated, with the U.S. election in November, and it may be a last chance for such outreach.

If Iran’s proxies are battered and new negotiations on the nuclear file are unproductive, there are strong voices inside Iran who argue to weaponize Iran’s nuclear program and achieve deterrence that way. Iran might also choose to deepen its relations with Moscow, hoping to get Russia’s advanced S-400 air defense system, since its current systems have proved vulnerable to Israel.

“Iran is at a fork in the road,” Vaez said. “Iran is assessing whether there is a path forward for nuclear diplomacy. But any war that would significantly weaken Hezbollah will make Iran feel less secure and could change their nuclear calculus.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

© 2024 The New York Times Company

Originally published on The New York Times