THE NEW YORK TIMES: How deadly Crans-Montana bar fire upended a Swiss town and left permanent scars

‘You cannot imagine seeing all those young people piled up in the bar, dead.’

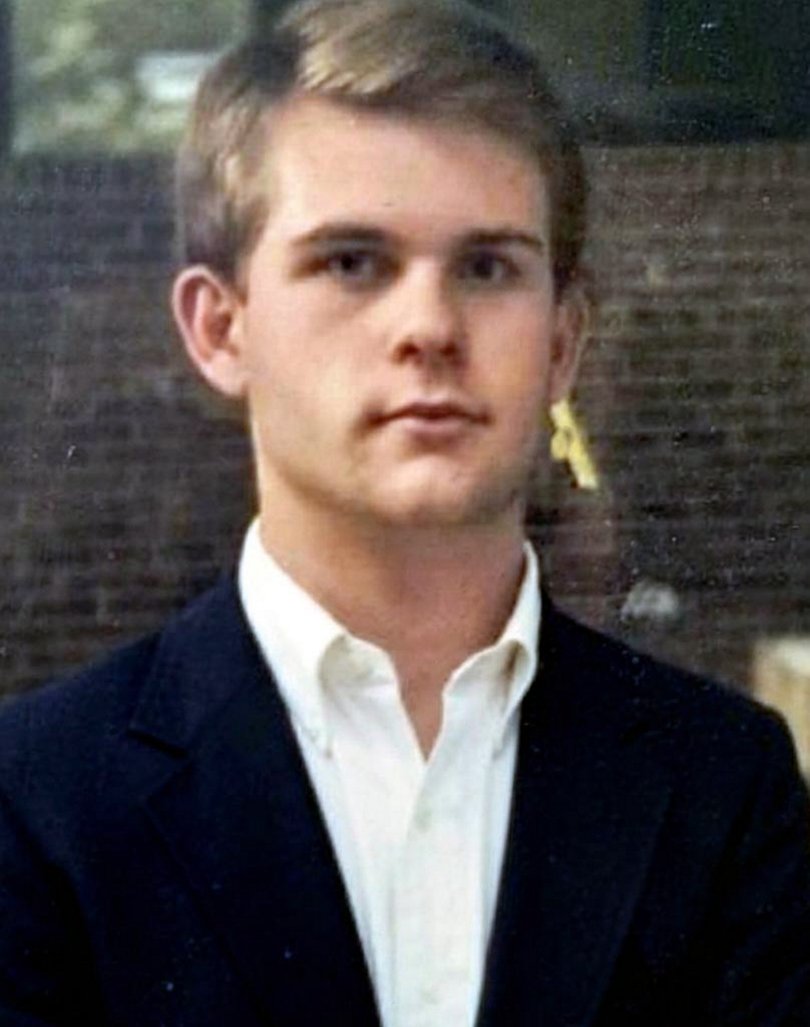

Skin is gone from Danielo Janjic’s cheeks, forehead, nose, ears. His hands are buried in layers of bandages, his face covered in ointments. Doctors have assured him that, with time and surgery, the burns will heal.

The searing trauma, however, will remain.

“I’m going to be scarred for life,” Janjic, 20, said recently from his hospital bed in Sion, a valley town about 15 miles from Crans-Montana, the ski resort in southern Switzerland where 40 people were killed and 119 were injured in a devastating New Year’s Day fire.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Many in this tight-knit community were still reeling Sunday as the identities of more victims trickled out. A teenager from Milan who loved to ski. The daughter of a city councilor. A promising Swiss boxer. The granddaughter of a local architect.

Investigators have identified all of the victims, police said Sunday, although they did not publicly disclose their names. Most were teenagers. The youngest was a 14-year-old Swiss girl.

For many in Crans-Montana, things will never be the same.

“You cannot imagine seeing all those young people piled up in the bar, dead,” Captain David Vocat, the local fire chief, said in an interview Sunday evening. “I don’t wish it upon anyone.”

Earlier in the day, Vocat and his team were applauded by hundreds who marched quietly to Le Constellation bar, the site of the fire, after a commemorative Mass at a local church.

“It’s small here. Everyone knows each other,” said Thérèse Auger, 68, a care provider for older people, who attended the packed service at the church, Chapelle St.-Christophe.

Outside, hundreds gathered in the cold to watch a livestream of the Mass on a giant screen. Church bells rang across the town’s pine-covered slopes before representatives from different faiths delivered words of solace in French, German and Italian.

“We are going through a period of crushing darkness,” the Rev. Gilles Cavin said later outside the bar, where residents sobbed, prayed

Identifying the badly burned bodies of the victims was a slow process, prolonging the agony of families searching for loved ones.

The death of Caroline Rey, 24, was announced Saturday by her father, Joël, who remembered the harrowing days after the fire when he would call her number to find “silence fills the air on the other end of the line.”

“This helplessness, this feeling of being unable to do anything but wait for that phone call that will change our lives forever,” Joël Rey, a city councilor in the nearby town of Sierre, wrote on social media. “And today, that unnatural call, which no parent in the world should ever receive, came.”

Andrea Costanzo, a former pharmaceutical company executive from Milan, told Corriere della Sera, an Italian newspaper, that he had received a similar call about his daughter, Chiara, 16. She had ended up at the bar with friends only because there was no room elsewhere, he said.

Chiara had three brothers, “was an excellent gymnast, skied flawlessly, loved nature, and spoke English like a native,” Costanzo said.

“Now I just feel a great emptiness.”

Pierre Pralong, a local architect, confirmed Sunday that one of his six grandchildren, Émilie Pralong, 22, had died.

In an earlier interview, Pralong said that Émilie, who was studying to become a teacher, had been “full of life and smiling and full of joy.”

Benjamin Johnson, a member of the Lausanne Boxing Club who was born in 2008, died trying to rescue a friend, according to Amir Orfia, the president of the Swiss boxing federation. Johnson’s friend survived.

“This ultimate act of altruism perfectly reflects who he was: someone who always helped others,” Orfia said in a statement that called Johnson “a promising athlete and a ray of sunshine.”

The two managers of Le Constellation have been placed under criminal investigation over suspicions of negligence as officials try to determine whether potential flaws in the site’s design and management contributed to the disaster.

Swiss police said in a statement Sunday that investigators believed that the fire had been caused by small fireworks in the bar’s basement. Witnesses and videos suggest that the fireworks were placed on bottles, sending up sparks that ignited foam insulation covering parts of the ceiling.

“Initial witness accounts describe a fire that spread rapidly, generating a lot of smoke and intense heat,” police said.

Janjic said that the fire tore through the bar’s basement as he fled and put his hands up to protect his face. Now he can barely move his fingers. Part of his back and buttocks were burned too, he said.

In the chaos of that night, it took several hours before the hospital administered painkillers to Janjic, who was born in Bosnia and raised in Switzerland.

“I couldn’t utter a single letter, because I was hurting so much,” he said. His hands have already been operated on, and he will be transported to a hospital in Sierre soon for plastic surgery.

“I feel weak,” Janjic said, tubes and catheters protruding from his arms as he shifted in his bed. “Sometimes I’m on the verge of tears, then I’m angry, then I’m sad — I don’t know.”

Vocat is also shaken.

His team of about 70 firefighters is now receiving psychological counseling. Almost all are volunteers who usually rush from their homes when needed, he said.

But on the night of the fire, many were already at the station to monitor New Year festivities. Things were going smoothly. Then, around 1:30am, the call came in.

Firefighters arrived within minutes, he said. The sudden burst of flames had ended, but people were streaming out of the smoke-filled bar. Screams pierced the air and bodies littered the ground.

Vocat insisted that the heroism of his team and of some of the young people had helped save lives. But after 11 years as fire chief, what he saw that night has made him question whether he wants to continue.

“No one should see this,” he said of the fire. “No one is ready for this.”

At the fire station, which has views of the snowcapped Alps, Vocat pointed to large cowbells in his office that belonged to his grandfather.

“Now that’s all I dream about,” he said of Switzerland’s famed alpine pastures. “Settling up there and living peacefully.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

Originally published on The New York Times