THE NEW YORK TIMES: The live music business is booming, now rap is getting a piece, too

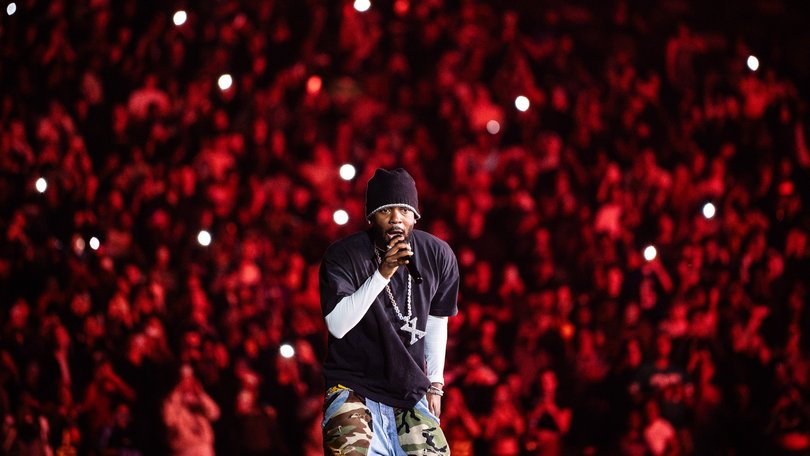

THE NEW YORK TIMES: While the pop girls dominate headlines, hip-hop artists have been gaining steam, running the touring market.

Live music has been booming for the past few years, bouncing back from pandemic shutdowns that shook the bedrock of the business.

While news about Taylor Swift’s record-breaking Eras Tour and rising ticket prices have garnered a lot of attention, an underrated touring market has been quietly gaining steam: hip-hop.

This summer Kendrick Lamar, Drake, Tyler, the Creator, GloRilla, Lil Baby, Lil Wayne and Wu-Tang Clan have packed arenas, amphitheaters and stadiums in the United States and abroad. An array of veterans and newcomers filled smaller venues this year, too, including Clipse, EST Gee, Nettspend, Xaviersobased and Billy Woods.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.In September, 25-year-old star YoungBoy Never Broke Again, who received a pardon from President Donald Trump in May after serving time on weapons charges, will embark on a highly anticipated arena tour that’s already selling well, especially for an artist who built a following with little radio success and live performance history. In fact, this will be the Louisiana rapper’s first headlining tour in his decade as a recording artist.

“There’s no shortage of artists wanting to go out and play,” said Mike Guirguis, who represents Lil Wayne and Young Thug.

According to Billboard Boxscore, live rap had its biggest year ever in 2024, with 5.7 per cent of the Top 100 tour grosses — still a relatively small piece of a very big pie.

Though it’s too soon to tabulate 2025, there has already been one record-breaker: Kendrick Lamar and SZA’s Grand National Tour is the highest-grossing co-headline tour in history, in any genre, with $256.4 million in North America. It places Lamar on a short list of rappers who have headlined stadium dates, alongside Eminem and Travis Scott.

Though the streaming era helped rap grow to become the dominant genre in terms of consumption, the live-performance side of the business has lagged.

Scott, a giant on streaming, had the biggest gross of any hip-hop artist in 2024, with $168.1 million across 69 shows. By comparison, Coldplay, the highest-grossing rock band of that year, more than doubled Scott’s take, with $400.9 million in 51 shows.

Because rap is largely a singles market — and since budding rappers are generally built in the studio rather than onstage — touring is often a second thought, and one that can be pushed aside in favor of one-off club performances, a hallmark of the genre.

Lingering anxieties about the safety of booking rap artists have had a cascading effect over the years, leading to artist teams with less experience putting together tours, and bookers and venues who don’t have a history with or knowledge of the music.

Guirguis said that over the past decade, rap artists and their managers have tried to change that by placing more emphasis on building a reliable touring business.

The hip-hop festival Rolling Loud, which debuted in 2015 and has hosted buzzy performances from a generation of Internet-made stars including Lil Uzi Vert and XXXTentacion, has provided a proof of concept for its contemporary profitability. In 2024, Rolling Loud Miami hosted 80,000 people per day.

Still, “If you want to be a career artist, you have to build your hard-ticket business,” said Guirguis, using a term for paying to see a specific artist’s show, as opposed to a festival ticket or a club night. Regardless of sales or streams, “if someone’s willing to buy a ticket to see you, you’re going to last for a long time.”

The temptation of earning fast money through nightclub appearances, where an artist needs to perform only two or three songs for tens of thousands of dollars, has contributed to hip-hop’s uneven touring business.

“The roots of the genre, and what a lot of rappers rap about, is the struggle,” said Jordan Stone, an agent who represents Veeze, Lil Tjay and Ian, among others. Touring requires a lot of money and assurances upfront, and profits often don’t roll in until later.

“Everybody doesn’t have the financing to go get on the road and wait for their money to come in,” he said. “I think that’s why the other path of getting quick money in the club was originally more appealing.”

Stone pointed to Future, who grossed $27.9 million across 21 arena shows last year, as an example of an artist who initially got mired in club appearances before embracing the road. “It took a few years for him to realize that, OK, this is not sustainable,” Stone said. Then, he “had to take a step back and probably had to come out of pocket just to tour the way he wanted to, to rebuild his business.”

Bias against rap has also long hindered the business. Concerns about safety at hip-hop concerts have persisted since the genre’s early days.

After a fatal stabbing in 1988 led Nassau Coliseum on Long Island, New York, to temporarily ban rap shows, a coalition of journalists, music industry executives and artists came together to combat the ensuing narrative, leading to the Stop the Violence movement and the song “Self-Destruction,” which featured KRS-One, Public Enemy, MC Lyte and others.

While tragedy has struck concerts featuring all kinds of pop acts, venues and law enforcement tend to focus on rap.

Ten years ago, a fatal shooting at Manhattan club Irving Plaza before a T.I. show resulted in a chilling effect on rap concerts in New York City, with William Bratton, the police commissioner at the time, decrying rappers as “basically thugs.” In recent years, the New York Police Department has removed local artists from festival lineups, citing safety concerns.

Multiple touring agents for hip-hop artists said that sometimes concert promoters need to be persuaded to book a rap show. Andrew Lieber, the touring agent for YoungBoy, noted that insurance for rap concerts is more expensive and sometimes more complicated to procure compared to other genres.

“I try to look at things through both lenses,” Stone said. “If I own the venue and I was bringing kids in there, no matter what genre it is, if it was associated with guns or violence, you’ve got to proceed with caution a little bit.”

Stone added, “A lot of the promoters are older people and may have been just booking rock and country acts.” He said it’s the responsibility of the agent to explain why they should be in the hip-hop business.

Lieber, 34, who is based in Silver Spring, Maryland, has focused on up-and-coming artists, developing them from 500-capacity rooms to arenas — a trajectory he mapped for artists including Juice WRLD, DaBaby, Rod Wave and Sexyy Red.

A former door-to-door salesperson and self-described disrupter in the live space, Lieber said he’s willing to do what larger agencies would not, including all-cash deals, covering travel expenses out of pocket, booking unsigned acts and plotting unusual touring routes.

“We’re not just building artists, we’re building careers,” Lieber said. “That’s something that I’ve created out of my mother’s basement with my bare hands, brick by brick. It’s an ecosystem that trains amazing agents and starts successful careers.”

Lieber is enthusiastic about the buzz for YoungBoy’s Make America Slime Again Tour, a 45-date jaunt where the rapper will pare down his large body of work into a night of fan favourites that have never quite crossed over into the mainstream.

“The first set list that came back had 200 songs on it,” he said, adding that YoungBoy has been rehearsing and working with Teyana Taylor on creative direction for the tour.

The show could put YoungBoy in league with touring powerhouses like Tyler, the Creator, whose Chromakopia: The World Tour has grossed more than $100 million through its first North American and European leg.

When Tyler first played New York in 2011 with his group Odd Future, the rowdy teens sold out no-frills venues like Santos Party House, a former art gallery. The first Odd Future festival appearance in 2012 was met with protests over the group’s violent lyrics.

Now, performing entirely alone without even a single backup dancer, he can sell out multiple nights at Barclays Center and Madison Square Garden. Kevin Shivers, his agent, said stadiums are in his future.

“He’s doing stadium business right now in arenas,” Shivers said, in terms of ticket sales. “He’s done the work and that’s where he’s headed.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

© 2025 The New York Times Company

Originally published on The New York Times