THE WASHINGTON POST: Trump’s answer to numbers he doesn’t like is ‘change them or throw them away’

THE WASHINGTON POST: Donald Trump’s fudged crime statistics are just one element in his manipulation of government data and risk a complete erosion of the public’s trust.

President Donald Trump presented inaccurate crime statistics to justify a federal takeover of DC police. He announced plans for the census to stop counting undocumented immigrants. And he ordered the firing of the official in charge of compiling basic statistics about the US economy after a weak jobs report.

This month marked an escalation in Trump’s war on data, as he repeatedly tries to undermine statistics that threaten his agenda and distorts figures to bolster his policies.

The latest instances come on top of actions the administration has taken across federal health, climate and education agencies to erase or overhaul data collection to align with the administration’s agenda and worldview.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.The president’s manipulation of government data threatens to erode public trust in facts that leaders of both parties have long relied on to guide policy decisions. A breakdown in official government statistics could also create economic instability, restrain lifesaving health care and limit forecasts of natural disasters.

Trump has routinely spread misinformation since the start of his political career, but his efforts in his second term to bend data to support his agenda have invited comparisons to information control in autocratic countries.

“What he’s trying to do is to present the best possible picture of what he’s doing, even if that means he has to cook the numbers, even if that means he has to distort the data,” said Robert Cropf, a political science professor at St. Louis University. “It’s basically a page from the authoritarian playbook.”

Trump has also tried to use his social media megaphone to influence data produced by private companies. On Monday, he called for Goldman Sachs to replace a veteran economist who produced reports that warned that tariffs could cause inflation.

But he may find himself in a game of whack-a-mole: On Thursday, a benchmark that measures the prices producers get for goods and services showed hotter-than-expected inflation, partly because of tariffs. Trump has not commented yet on the report.

Other countries have demonstrated the risk of undermining statistics, which can erode citizens’ trust in their government and nations’ standing in the international community.

China has been widely accused of inflating economic figures, prompting other countries to seek alternative data sources for a more trustworthy picture of the nation’s financial situation.

In Greece, the government produced false deficit numbers for years, and the government repeatedly sought to criminally prosecute the statistician who produced accurate budget figures.

Argentina manipulated economic statistics for years to minimise the extent of inflation, even as consumers paid for significantly more expensive groceries and goods.

The false deficit numbers in Greece contributed to the country’s debt crisis. The cooked numbers in Argentina made it more difficult for the government to enact policies that could limit inflation, and citizens lost faith in the ability to trust the government data to inform major purchases.

White House spokeswoman Taylor Rogers said that the president’s actions are intended to “restore” Americans’ trust in data so they can make their own decisions.

“President Trump is preserving - not eroding - democracy by ensuring that the American people can rely on government data that actually reflects reality,” Rogers said in a statement.

Government statistics have traditionally been considered more reliable and comprehensive than those collected by private sector companies motivated by profits, said Paul Schroeder, the executive director of the Council of Professional Associations on Federal Statistics.

The data is needed to provide an accurate picture of what is happening. Without it, governments, corporations and individuals lack information that can inform decisions about everything from mortgage rates to weight loss.

“It’s almost like an airline pilot losing his instrument panel when driving the plane,” Schroeder said of the erosion.

Trump’s decision to fire Bureau of Labor Statistics Commissioner Erika McEntarfer was widely condemned by statisticians and economists, who warned that the move could have a chilling effect on the work of federal number crunchers who produce reports the president doesn’t like.

Trump claimed without evidence that the nation’s job statistics were “rigged,” following a revision to the May and June jobs figures that showed the labour market was weaker than previously known.

Revisions to job reports are common, but many economists have acknowledged falling response rates to government surveys, and long-standing budget strains have made it harder for economic agencies to collect and analyse reliable data.

“President Trump believes that businesses, households, and policymakers deserve accurate data to inform their decision-making, and he will restore America’s trust in the BLS,” Rogers said.

Trump’s attempts to change how the government collects data have invited backlash, especially his proposal to overhaul the census amid a fight over redistricting.

Civil liberties groups have said they would challenge any attempt to change the census, warning that the president’s proposal to eliminate undocumented immigrants from the count could erode the political power and financial resources of diverse communities.

The census is used not only to determine congressional seats but also to distribute federal funding and decide where to build schools.

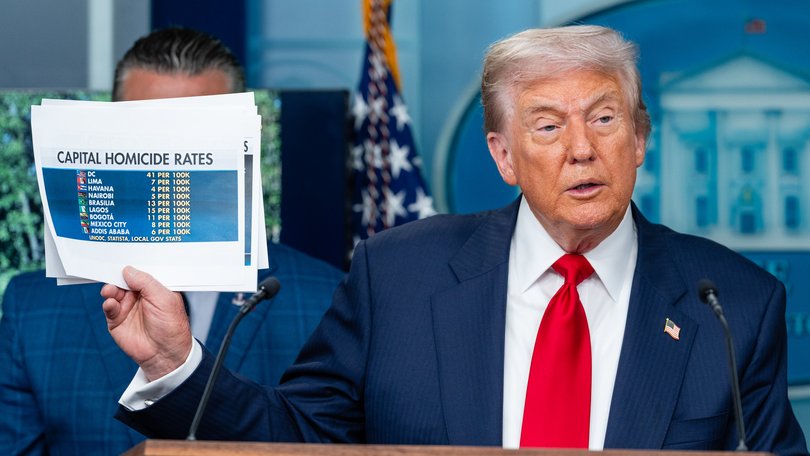

Trump justified his decision to deploy federal law enforcement and the National Guard on DC streets with claims that crime is surging in Washington, but violent crime in DC has been on the decline since 2023.

The White House has cast doubt on the accuracy of local statistics, citing a July NBC News report that said that the District suspended a police commander accused of manipulating crime numbers in his district.

Rogers added that the data “doesn’t change the on-the-ground reality that many D.C. residents and visitors have experienced on our streets.”

In other instances, the administration has halted the collection of data that advocates and experts warn is essential for Americans’ well-being and safety.

At the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, scientists are now forbidden to collect gender data on any programs. That includes abortion data and information for sexually transmitted disease prevention, violence prevention and mental health programs.

The lack of data could undermine efforts to prevent the spread of STDs and prevent school shootings and suicides.

Federal collection of abortion data stopped on April 1 following widespread layoffs across the Department of Health and Human Services.

Most states put out their own abortion data, but no other federal agency collects abortion data, according to a former CDC employee familiar with those programs. The government uses the data to predict birth rates, a crucial statistic that governments and businesses use to make decisions about the health system, education and the economy.

CDC staff members are also no longer collecting concussion data for the creation of a concussion surveillance system, which has had strong bipartisan congressional support. The agency is also no longer analysing data to prevent drowning - the leading cause of death in children aged 1 to 4 - because all of those staff members were laid off.

Researchers have warned about the diminishing of data programs that are key to understanding the ever-evolving drug crisis in the United States - and to building the best prevention and treatment programs.

In June, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration stopped updating the Drug Abuse Warning Network, a nationwide surveillance system of drug use trends and insights drawn from emergency department visits.

The loss of that data will make it more difficult for researchers such as Daniel Ciccarone, a professor at the University of California at San Francisco School of Medicine, to track street drugs and overdoses. Ciccarone studies trends in the fentanyl supply, which kills tens of thousands of Americans each year, as well as new synthetic drugs seeping into regional supplies.

“We need surveillance data at a historic time of an undulating drug supply - we don’t know what’s going to happen next,” Ciccarone said.

Public health advocates have raised concerns about the future of the National Youth Tobacco Survey, an annual report that measures how young people are using nicotine products.

The report helped alert the country to the epidemic of teen vaping and led to stricter controls on the industry. The program has long been run through the Food and Drug Administration and the CDC’s Office on Smoking and Health, which was shut down in the spring.

An HHS spokesperson did not respond when asked about the future of the survey, saying only that the CDC “remains deeply committed to tobacco prevention and control and … continues to support this critical public health priority through a range of efforts, including outreach, education, and surveillance.”

The Trump administration has also discontinued dozens of climate databases and government-funded studies, including efforts to quantify the damage caused by natural disasters and to understand how the heaviest rainfall will intensify as the planet warms.

Officials have removed key climate data and reports from the internet. The administration took down the website of the U.S. Global Change Research Program, which shared congressionally mandated reports about climate change impacts across the country.

And it deleted climate.gov, a repository for research and forecasts, though it said such information would continue to be posted on a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration website.

Trump’s budget proposal for NOAA would eliminate nearly all of the agency’s labs focused on climate, weather and oceans - institutions whose studies are key to weather and climate forecasting and improving our understanding of everything from summer thunderstorms to the El Niño climate pattern. Businesses rely on this data to inform plans for tourism, fisheries and shipping.

The changes reflect the administration’s commitment to “eliminating bias and producing Gold Standard Science research driven by verifiable data,” Rogers said in a statement.

As the Trump administration attempts to shutter the Education Department, its ability to publish accurate and timely data was thrown into question after deep cuts to the department’s staff.

Virtually the entire staff of the National Center for Education Statistics was laid off, and while much of the work is done by contractors, researchers worry that there are no longer enough government workers to check and disseminate collected data.

The centre’s work is critical to researchers, policymakers and journalists, with a wide range of data including the demographics of students and schools, courses offered, crime on campuses, and school spending.

Already, the Education Department missed its June deadline to publish the annual Condition of Education report, the authoritative source for education data from preschool through university. The agency has continued to publish some data tables but far fewer than in past years.

The Trump administration has also called for more information about the consideration of applicants’ race in college admissions.

“Greater transparency is essential to exposing unlawful practices and ultimately ridding society of shameful, dangerous racial hierarchies,” Trump said in a memorandum issued last week, as he ordered the Education Department to begin collecting detailed data from all colleges that receive federal financial aid.

That includes grades and test scores for both applicants and students, broken down by race.

The White House has argued that a lack of data has hindered enforcement of a 2023 Supreme Court ruling that the use of race-conscious admissions is unconstitutional.

But a higher education leader argued that the information requested won’t provide good data: Applicants don’t disclose their race, and while colleges do survey students who enroll, participation is voluntary, and even those who respond may choose not to disclose their race.

“They’re going to gather a bunch of information and try to make sense of it,” said Ted Mitchell, president of the American Council on Education. “I worry that they’re not going to be able to make much sense of it.”

The impact of these changes could affect the nation long after Trump leaves office, Cropf said. Even if the government resumes collecting data, there will be gaps from the Trump era, and the public may view the figures as more politicized.

“It taints the waters,” he said. “It seriously undermines faith in our institutions if we can’t have any guarantees the institutions are providing us with reliable data or that they’re making decisions based on reliable data.”

- - -

Lena H. Sun and Susan Svrluga contributed to this report.

© 2025 , The Washington Post