JOHN McDONALD: Iris van Herpen’s fashion offers a Hieronymus Bosch-style Garden of Earthly Delights

JOHN McDONALD: Consulting with boffins on the Large Hadron Collider or turning splashes of water into ‘impossible’ dresses: Iris van Herpen is literally taking fashion to another dimension.

When you’re born in the same town as Hieronymus Bosch, it’s a hard act to follow.

In the Prado in Madrid, visitors stand transfixed in front of Bosch’s triptych, The Garden of Earthly Delights (1490-1510), with its outlandish visions of heaven and hell, the former packed with exotic animals, the latter a nightmare scene of sinners being tortured and devoured by demons. After more than 500 years we’re still arguing about what it all means.

Iris van Herpen (born 1984) grew up in the village of Wamel, 30 minutes drive from Bosch’s hometown, ‘s-Hertogenbosch. There must be something in the water because the young Dutch designer has done for contemporary fashion what her predecessor did for Northern Renaissance painting.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.It feels somewhat inadequate to call van Herpen a designer. As revealed by an extraordinary survey at Brisbane’s Gallery of Modern Art, she is the complete artist, with a body of work that recognises no physical or conceptual limitations.

Iris van Herpen: Sculpting the Senses is one of the highlights of the museum year in Australia, if not the world. Brisbane is the only local venue for this show, put together by the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris last November.

Van Herpen originally studied classical and contemporary dance, giving her an understanding of the body in motion that has been fundamental to her work.

At the age of 21, she served an internship in London with Alexander McQueen, arguably the most acclaimed fashion designer of the 21st century. Two years later she started her own fashion label in Amsterdam. By 2011, aged all of 27, she had been ushered into the Chambre Syndiale de la Haute Couture in Paris, as a guest member.

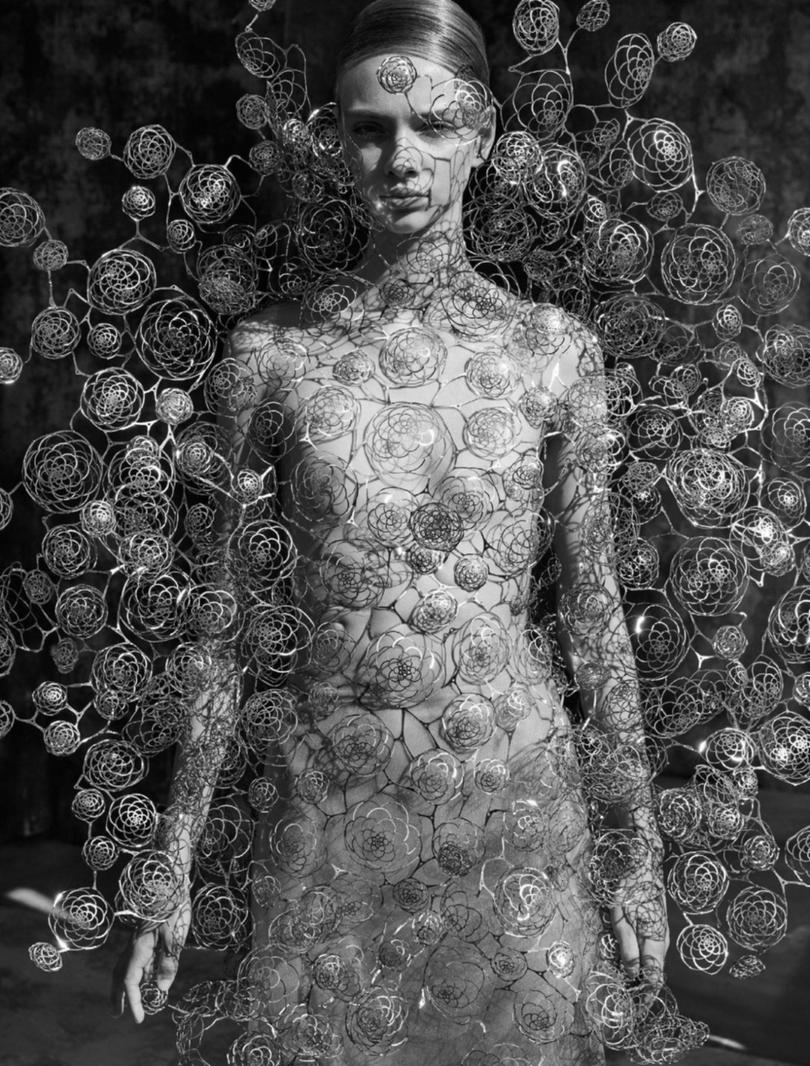

This kind of meteoric success is not down to luck, or even hard commercial nous. What’s most remarkable about van Herpen’s rise to prominence is that she has done it through the strength of her ideas and the originality of her designs. Even today, there are no Iris van Herpen boutiques, no ready-to-wear lines, no accessories licenced to sell in department stores. Most of her dresses are one-offs, incorporating unique materials that have been fabricated by machines, but stitched together by hand, combining the latest technology with the age-old skills of haute couture.

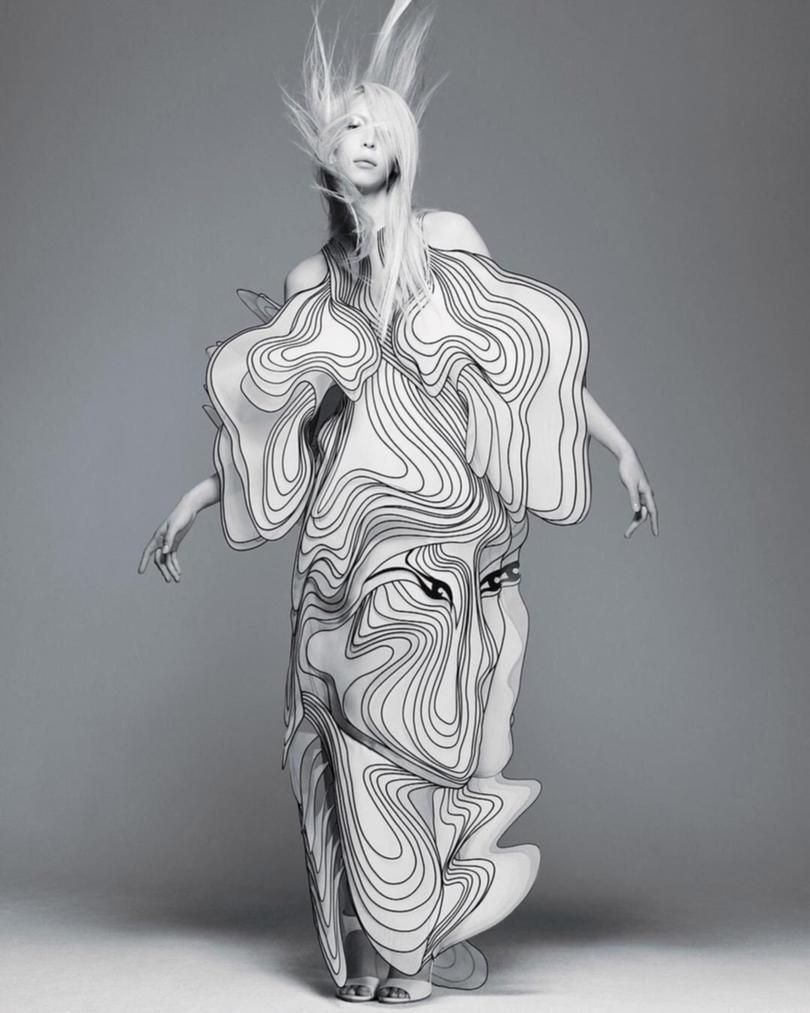

Looking at the 100 dresses in this exhibition it seems that few people could wear them, and nobody could sit down in some of them. They are sculptures made for the catwalk, as seen in numerous videos of models marching down the runway, each new creation more startling than the last.

Van Herpen’s outfits have been boosted by celebrity power, being worn by figures such as Björk, Lady Gaga, Tilda Swinton, Beyoncé, Jennifer Lopez, Céline Dion, Grimes, and even Cate Blanchett. These stars have appeared at events such as the annual Met Gala in full regalia, usually changing into something more practical for dinner. The central corridor at GOMA is lined with celebrity photos.

Even more impressive than van Herpen’s list of clients, is the long line of artists, architects, scientists, engineers and technicians with whom she has collaborated. The most consistent of the lot may be her partner, musician, Salvador Breed, who has provided a soundscape for the exhibition. With every collection, van Herpen has gravitated towards people who have specialised skills to help her realise her ambitious projects. She has said, “I often get inspired by the materials I cannot work with.”

In the case of her Water dress of 2013, she was told that what she wanted was “technologically 99 per cent impossible”. Her solution was to have model, Daphne Guinness, stand naked while buckets of water were thrown at her. The action was recorded on video and the freeze frame images transferred to sheets of clear plastic that van Herpen cut and twisted by hand until she had a dress resembling an explosive splash of water.

In any other fashion exhibition, the Water dress would be a standout, but in this survey, it’s just one among many “impossible” feats. There are nine sections, exploring not just the physical properties of water, but the creatures that live in the ocean, even extinct ones, as seen in the Ammonite Dress (2016). There are dresses based on bones and exoskeletons.

There’s a Cathedral dress (2012), which looks as if a Gothic cathedral has been taken apart, shrunk and flattened, so it can be wrapped around a human body. An even more extreme artefact is the Moon dress (2013), made from iron filings mixed with resin, replicating the surface of the Moon, in a shell as hard and heavy as stone. Van Herpen’s Foliage dress (2018) appears to be made from leaves, her Snake dress (2011), is a tangle of black serpentine forms.

I could go on listing these surreal outfits, but they really have to be experienced first-hand to appreciate the way each garment relates to the body, suggesting sinuous, rippling movement.

Van Herpen’s innovations extend to the way her dresses have been displayed. Skydiver, Domitille Kiger, has flown through the clouds in a long flowing dress. Julie Gautier, a champion free diver, has worn one in the depths of the ocean. In another video, lacy dresses from the Earthrise collection (2021), adorn models standing on snowy mountain peaks.

In 2010, van Herpen became one of the first designers to explore the possibilities of 3D printing, a process that has become crucial to her work. As the technology has continued to evolve, so too have her designs grown more complex and far-reaching. A typical piece may be constructed from many hundreds of 3D printed components, stitched together by assistants in her Amsterdam studio.

It’s commonplace for leading couturiers to borrow ideas and motifs from the visual arts. In 1965, Yves Saint-Laurent based an entire collection of cocktail dresses on Mondrian’s geometric paintings.

Van Herpen, however, is not a borrower, having worked closely with artists such as Canadian sculptor, David Altmejd; Britain’s Rogan Brown, whose mind-boggling papercuts are featured in the show; and American, Kim Keever, who releases pigments underwater and photographs the coloured blooms that result.

She has also worked with scientists, making multiple visits to the Large Hadron Collider, which stretches for 27 kilometres, along the Swiss-French border, near Geneva. These visits inspired her Aeriform collection (2017), which explores the properties of light and air.

A large part of the GOMA exhibition is devoted to van Herpen’s sources of inspiration, which are so various as to defy listing and complementary works by Australian artists. These include an engraved metal panel by Gunybi Ganambarr and a massive curtain of oyster shells by Megan Cope. There’s also a slab of the most perfectly preserved fossil crinoids borrowed from the Queensland Museum. The ancestors of our starfish and sea urchins, predate the dinosaurs by 300 million years.

I can’t recall ever seeing an exhibition that ranges so freely between the macrocosm and the microcosm, between nature and culture, between the cosmos and the world discovered through the lens of a microscope.

Is this haute couture? Only incidentally. There’s no simple way to label or define this boundary-breaking work, which makes most contemporary art and fashion look banal in comparison.

If you spend your life in museums, as I do, it’s rare to be completely blown away by an exhibition, but this is one of those rare occasions. In this survey, Iris van Herpen has provided a Garden of Earthly Delights that puts Hieronymus Bosch in the shade.

Iris Van Herpen: Sculpting the Senses

Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane,

29 June – 7 October 2024

John McDonald is one of Australia’s best-known and respected art critics, having spent more than 40 years reviewing visual arts, fashion, film, journals, and books. McDonald was the senior art critic for The Sydney Morning Herald for 41 years and was also well known for his weekly film column in that time. He has also worked as the Head of Australian Art at the National Gallery of Australia.