THE NEW YORK TIMES: Giorgio Armani, fashion’s master of the power suit, dies at 91

THE NEW YORK TIMES: Giorgio Armani rewrote the rules of fashion not once but twice in his lifetime.

Giorgio Armani, a designer who rewrote the rules of fashion not once but twice in his lifetime, died Thursday at his home in Milan. He was 91.

His death was announced by his company, the Armani Group, which said he had been working “until his final days.”

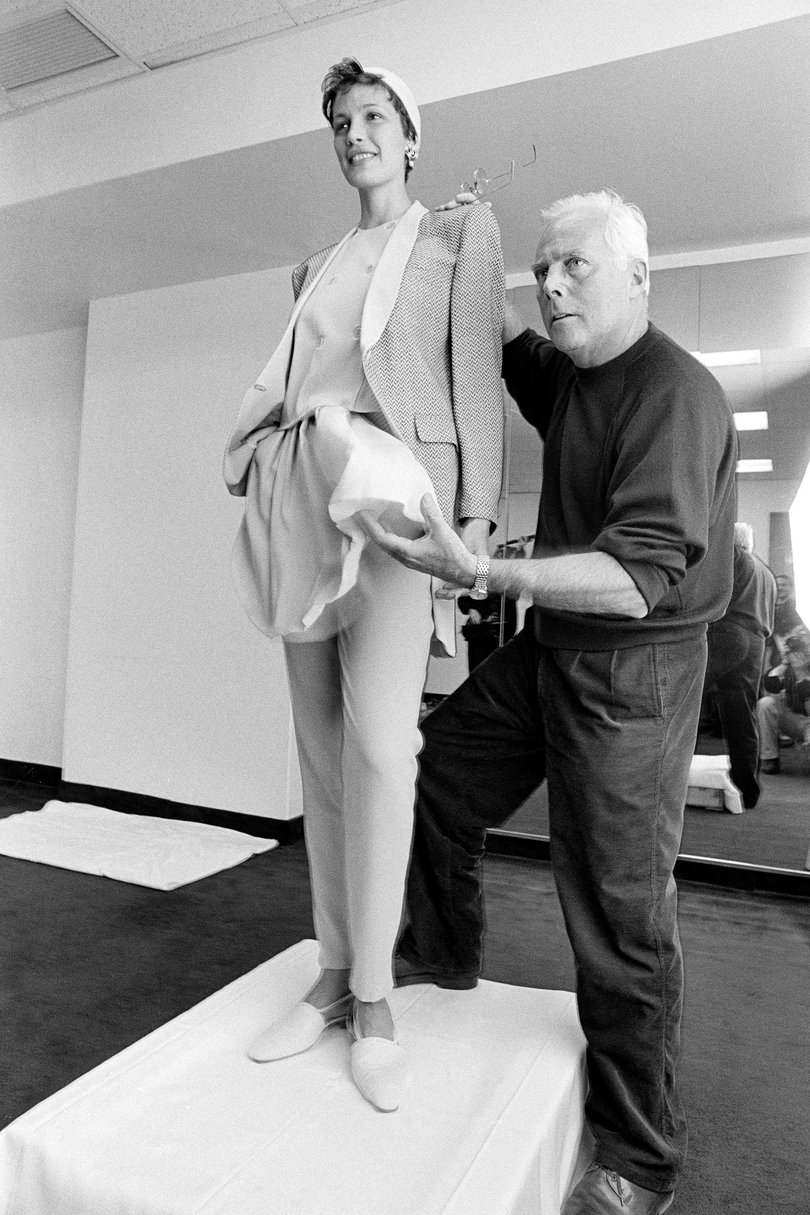

A reluctant designer but an instinctive empire builder, Armani initially became a household name by adapting a custom from traditional Neapolitan tailors: softening the internal structure of a man’s suit to reveal the body inside. Simply by removing shoulder pads and canvas linings, Armani devised what in the early 1980s became a new male uniform, the easy and almost louche sensuality of which soon enough found favor among a female clientele.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.“All the women of my generation, including Hillary Clinton, were wearing jeans in the 1960s,” said Deborah Nadoolman Landis, a costume designer and historian, and founding director and chair of the David C. Copley Center for the Study of Costume Design at UCLA. “But where do you go from Woodstock? How do you professionalize that look when those women start entering the workforce? You professionalize it by wearing a feminized suit from Armani.”

Androgynous, luxurious, positioned somewhere between the stuffy establishment attire popular among male executives at the time and the prim skirt suits favored by many professional women, Armani’s designs offered an alternative form of power dressing.

For a time, in Wall Street corner offices, Madison Avenue boardrooms and the executive suites of many Hollywood talent agencies, an Armani suit was the default uniform of authority, an occupational armor rendered in crepe or cashmere and cast in a somber palette from which the designer would seldom stray.

“Armani is one of those, like Coco Chanel with the little black dress, as important for what he contributed socially through dress as for what he specifically designed,” said Harold Koda, a former head curator of the Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art who was a curator, with Germano Celant, of an Armani retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum in New York in 2000.

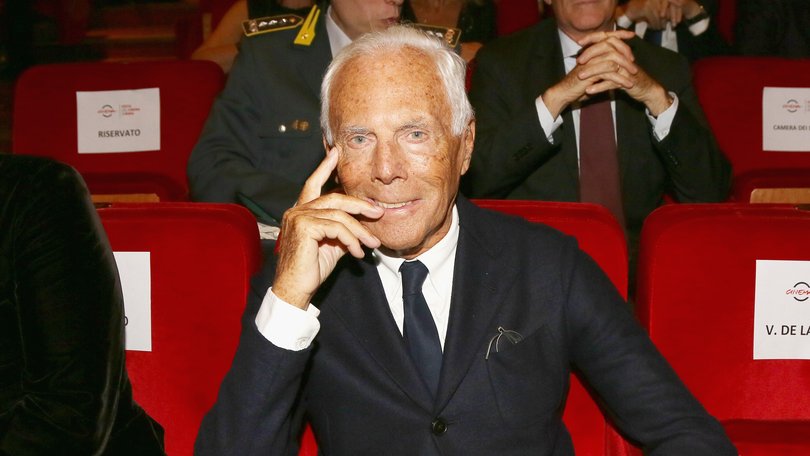

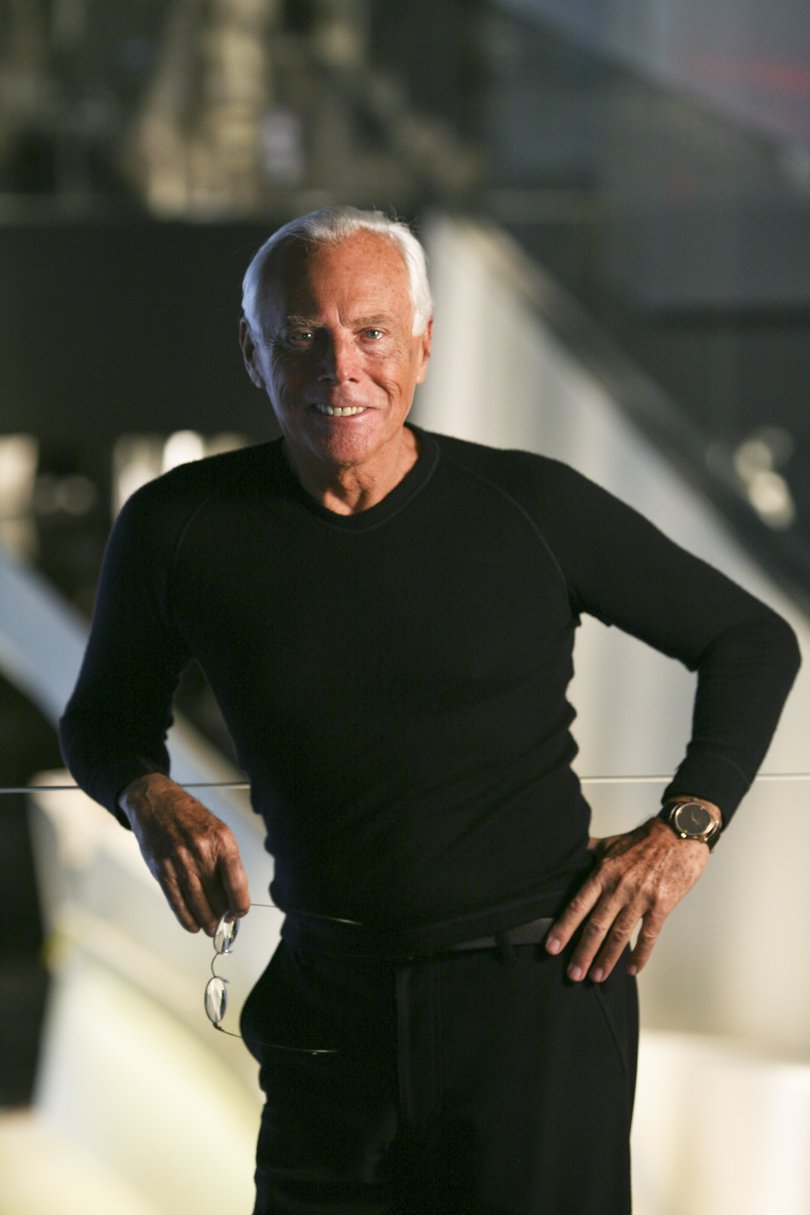

Early to embrace and mythologize Armani, the fashion press was initially magnetized by him as much for his cinematic good looks — piercing blue eyes, a mahogany tan and an athletic physique he would enjoy displaying well into his 80s — as for the assured yet ascetic aura he projected at a time when fashion designers had begun to emerge as pop culture celebrities in their own right. In the Italian media, he was lionised as “King Giorgio.”

Eventually, the fashion flock would move on from a design vocabulary his critics occasionally derided as repetitive and out of step. Yet if this troubled Armani, he never let on, possibly because the colossal advertising budgets deployed by his family-held company (which in 2023 posted revenues of $2.65 billion) all but guaranteed his work would receive lavish and largely reverent coverage in the press. As it turned out, the unruffled self-assurance he maintained was validated when, in recent years, the pendulum swung back to the styles of the 1980s, and Armani was once again lauded as a style prophet.

Alliance With Stardom

Although anything but camera shy, Armani nevertheless viewed himself less as a performer in what he once termed “the movie of life” than as its presiding spirit. And cinema, as he declared in “Made in Milan” (1990), a 20-minute documentary about him directed by Martin Scorsese, had always been his true love.

“I would like to have been a director,” Armani said in the film. “The passion is still in my blood.”

In certain ways, it was this passion for the movie world, and for a constantly changing roster of the genetically favored, that would result in what is generally considered Armani’s most durable contribution to his field and his second recasting of fashion’s canon. Sooner and perhaps better than anyone else in the industry, he aligned himself with movie stars and their putative glamour, in the process making his name all but synonymous with red-carpet dressing.

By now, the symbiosis of celebrity and fashion is so institutionalized that few are surprised to see stars stepping out for designers as glamorous and well-remunerated sandwich boards. But Armani was among the first to court them, going so far as to establish a corporate beachhead in Hollywood to identify and cater to the sartorial needs of the occupationally fabulous.

“Giorgio started the whole thing of giving clothes to celebrated people, public figures,” said model and actor Lauren Hutton, who portrayed a senator’s wife in “American Gigolo” (1980), the film often credited with introducing Armani’s designs to a mainstream public. “Designers really didn’t give away clothes back then.”

Yet Armani did so, and lavishly, with the result that movie stars such as Michelle Pfeiffer, whom he referred to as an early muse, could be relied upon to appear at awards shows in clothes that boosted their currency in the emerging realm of fashion as mass entertainment.

“I was one of the first designers to dress stars on and off screen,” Armani told the British newspaper The Telegraph in 2013. “They didn’t always have a particular style, or the dress sense to know what to wear for an occasion. I helped them feel more confident and relaxed.”

Dressed in a powder-pink evening suit and satin gloves by Armani for the 1992 Academy Awards ceremony, actor Jodie Foster — who until then had never been anyone’s idea of a fashion plate — both won an Oscar and was suddenly propelled onto the International Best Dressed List.

In the decades to come, Armani would ignite countless paparazzi flashes as female celebrities such as Gwyneth Paltrow, Cate Blanchett, Sophia Loren, Julia Roberts, Beyoncé, Lady Gaga, Cindy Crawford and Glenn Close appeared in his lavishly beaded, embroidered and typically form-hugging evening clothes, and men such as Russell Crowe and George Clooney preened themselves in his impeccable tuxedos.

“Armani gave movie stars a modern way to look,” Anna Wintour, until recently the editor-in-chief of Vogue, once said. More aptly, he gave them an old-fashioned way to look, one that harked back to the so-called Golden Age of Hollywood.

A Household Name

Fittingly, it was through film that Armani first entered mainstream consciousness as a designer, when critics and audiences alike thrilled to a scene in which a bare-chested young Richard Gere, portraying a high-end escort, selects his evening’s wardrobe from an array of sensual earth-tone suits and knit ties in Paul Schrader’s noir tale “American Gigolo.”

In that film, Gere “succeeded in displaying the sensual, natural feel of my style and the new relationship between the garment and the body it represented,” Armani told The Telegraph in 2013.

“Thanks in part to that film, my label rapidly became a household name,” he added, notwithstanding an ongoing debate about whether, in truth, Gere wore anything by the designer on screen.

As Landis, the costume historian, said, the only actual Armani in the movie “is what you see Richard Gere looking at in his closet and on his bed, the folded clothes.”

It little mattered, she said: “There was a magical synchronicity between that moment in men’s fashion, film and Armani’s career.”

Unquestioned is the effect Gere’s bristling, insolent sexuality in “American Gigolo” had on men’s fashion, and the shift it triggered in the rules of dressing. This was as true in the sports arena as in the boardroom, as witnessed by the elevation of Pat Riley, then head coach of the Los Angeles Lakers, from the arena sidelines onto the cover of GQ.

Armani’s designs would be seen on screen as well as off, worn by stars such as Sean Connery and Robert De Niro in “The Untouchables” (1987); by Christian Bale and Michael Keaton in separate iterations of the “Batman” franchise; by Leonardo DiCaprio in “The Wolf of Wall Street” (2013); and by Don Johnson in the hit 1980s police drama “Miami Vice,” in which a pale Armani jacket over a T-shirt created another new template for casual attire.

And he would prove himself an instinctive and canny industrialist, one whose name would be attached to multiple clothing lines, fragrances, cosmetics, shoes, watches, jewelry, hotels and restaurants; as many as 250 movie, opera and theater productions; and uniforms worn by Alitalia flight attendants and English and German soccer teams — and whose business model (20 per cent of the products earn 80 per cent of the profits) became a standard element of training in fashion academies.

An Interest in Medicine

Giorgio Armani was born July 11, 1934, in Piacenza, a town on the Po River about 45 miles south of Milan. He was the middle of three children of Maria Raimondi and Ugo Armani. His father was employed before and during World War II as a clerk in the offices of the local Fascist party.

Movies were Armani’s first love. He often attended them with his father, finding in the darkened cinema his one reliable means of escape from the terrors of life in wartime Italy. Early in life, these were anything but remote abstractions; when Allied forces began a concerted bombing campaign in 1940, strafing Italy north to south from Turin to Naples, his family home was struck by a shell.

Although the family emerged unscathed, Armani was severely injured shortly after the end of the war when a live mine detonated on a street near his home and set him ablaze. He was not yet 10.

During six weeks of convalescence, doctors kept the boy’s eyes swathed in bandages. They removed his burned skin by soaking him with alcohol. “I suddenly closed my eyes and didn’t open them again for 20 days,” Armani said in a 2015 interview with Harper’s Bazaar. “I could smell the linden trees in the hospital gardens in bloom, but I couldn’t see them. It was hard for me because they weren’t sure if I would ever be able to see again.”

He eventually recovered, the single visible reminder of the incident a scar where a shoe had burned into his foot. As a result of the experience, he would later set his mind on pursuing a career in medicine, which he had come to view as a noble and selfless profession.

“A.J. Cronin’s books about being a country doctor made a deep impression on me,” he wrote in his autobiography, titled simply “Giorgio Armani” (2015). “I loved the idea of a person who saved the lives of the elderly and the young alike.”

Educated initially at the Liceo Scientifico Respighi in Piacenza, Armani moved with his family to Milan in the late 1940s and, after high school, studied medicine at the University of Milan. After a brief and unpromising stint there, he broke off his studies to join the army; owing to his medical training, he was assigned to work in an infirmary. There was little enough about his beginnings to suggest his eventual trajectory.

“Fashion played no part, at least no apparent one, at this point in my life,” Armani said in his autobiography, referring to his youth. “There seemed to be no trace of the spark of inspiration or sacred muse that most people talk about when asked how they got started.”

Nevertheless, he had always admired fashion and would recall having been the envy of classmates for the stylish outfits his mother sewed for him and his siblings. “We looked rich even though we were poor,” said a man who would go on to amass a fortune estimated at $11.5 billion, rendering him among the richest people in Italy.

It was largely happenstance that led Armani to fashion — and a temporary job at the Milan department store La Rinascente in 1957. Employed initially as an assistant photographer and window dresser, he was rapidly promoted to buying supervisor, charged with purchasing goods from India, Japan and the United States.

His talents as a stylist quickly came to the attention of menswear designer Nino Cerruti — scion of a family textile business and widely considered a paragon of Italian elegance — and so in 1964, with no formal fashion training, Armani found himself at the helm of Hitman, a Cerruti line of men’s clothes.

He remained at that job until 1970, when, nearing 40, he impulsively struck out on a career as a freelance designer. In that pursuit, he was encouraged by Sergio Galeotti, an architectural draftsman he had met in the 1960s at La Capannina di Franceschi, a storied discotheque in the resort town of Forte dei Marmi, who soon became his lover.

“It was Sergio who believed in me,” Armani told GQ in 2015. “Sergio made me believe in myself. He made me see the bigger world.”

Throughout his long career, Armani paid particularly close attention to textiles. He also displayed an aptitude for juxtaposing materials and textures, employing plush woolens traditionally restricted to womenswear for men’s suiting or treating leather like cloth. His earliest press raves came for a softly styled leather bomber jacket he designed and showed at the Sala Bianca fashion show in Florence in 1974.

Using as part of their grubstake the proceeds from the sale of their Volkswagen Beetle, Armani and Galeotti formed their own company and label in 1975. Soon after that, the designer introduced his career-defining unlined jacket, a design that signaled a definitive turn away from traditional male business attire. He then went on to introduce a woman’s version whose sexy though sober styling was a welcome contrast to both the dull separates then available to executive women and the frothy concoctions featured on many runways in an era of pouf skirts and giddy excess.

So rapid was Armani’s rise that by 1982, he had appeared on the cover of Time. He was the first fashion designer to be so featured since Christian Dior four decades before.

But according to Koda, the curator, he was even then not without his detractors.

“Eleanor Lambert, in the mid-’80s, said that Armani had destroyed fashion,” Koda said, referring to the publicist largely credited with having laid the groundwork for fashion as a form of mass media. “She thought he’d created a new uniform that was so consistent, it made anything that looked merely fashionable look transient and disposable.”

Grief Takes a Toll

With this early phase of his success at its peak, Armani received the news that Galeotti, his partner, was infected with HIV. At the time, there was no effective treatment for the virus; Galeotti died at 40 in 1985. Although news accounts attributed the death to a heart attack, the cause was widely understood to have been complications of AIDS.

“During that dreadful year I lived as though I were holding my breath, without thinking about the inevitable, working day in and day out,” Armani wrote in his autobiography. Compounding his grief was the burden of taking on the business side of the company. “Most people,” he said, “thought I wouldn’t be able to make it.”

Musing on his own nostalgic nature in “Made in Milan,” Armani said, “I love the past, but I try not to be its victim.”

In the eyes of some critics, his work in the years following Galeotti’s death sometimes left the impression that in his struggle with it, the past had won. In the early years of this century, he gave his shows nostalgic titles like “Echoes of Armani” and sent onto the runway softly tailored menswear whose unmistakable homoerotic charge seemed lost in an earlier time.

Yet if his aesthetic sometimes faltered, his business acumen never did. The Armani empire at his death was a high-octane machine, with a globally legible brand name and outposts in most major cities throughout the world.

“I have chosen work as my way of life,” Armani told Scorsese.

And while the material rewards of his labors were vast — they included an immense 18th-century Milanese palazzo, a penthouse on Central Park West; a cliff-hanging retreat in Antigua; a chalet in St. Moritz; a Provençal farmhouse; a sprawling compound on the rocky Sicilian island of Pantelleria; a villa in Lombardy; a 48,000-square-foot museum devoted to his archives; and a custom 213-foot yacht christened with his mother’s childhood nickname — he remained in some sense an oddly isolated and ascetic figure, one whose routine often included dinner at home with the television on and accompanied by Angel and Mairi, his cats.

Although by his own account, Armani never entered into another partnership as intimate and significant as that with Galeotti, he maintained a decades-long relationship with Pantaleo Dell’Orco, an Armani executive and board member of a charitable foundation the designer created in 2017 to forestall future takeovers of the multibillion-dollar, privately held company. In recent years, Dell’Orco joined him at the conclusion of each fashion show for the signature bow.

In addition to Dell’Orco, Armani is survived by his sister, Rosanna. His brother, Sergio, died in 1996.

Until the very last, Armani remained resolutely tight-lipped about his succession. “There will be plenty of time for others later,” he told GQ. “As long as I am here, I am the boss.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

© 2025 The New York Times Company

Originally published on The New York Times