Victoria’s Secret returns: Iconic fashion show is back but will it handle a post-MeToo world

From 1995 to 2018, the Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show was the nexus of pop culture, fashion, entertainment, and an all-American view of ‘sexiness’. Then, abruptly, the party was over.

It was the hair extensions that got me. Backstage at the 2012 Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show in New York City, I was surrounded by dozens of models generally acknowledged to be some of the world’s most beautiful women – all being ministered to by cadres of hair, make-up and spray-tan artists.

Instead of interviewing supermodel Alessandra Ambrosio about how it felt to wear the $US2.5 million ($3.7m) Floral Fantasy Bra like I was supposed to, I stood stock-still in front of a table piled high with hanks of human hair.

There was just so much of it. If a Pompeii-esque catastrophe froze this moment, I thought, and future archaeologists inspected the Lexington Avenue Armoury for clues about our civilisation, they would conclude that we ancients worshipped at an altar of big hair.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.In my 16 years covering the fashion industry, I’ve rarely attended a show that involved glitter confetti – nor mountains of hair extensions, crystal-embellished wings, Grammy-winning musical acts or an army of supermodels in underwear. Let alone all of the above. But this wasn’t just any show.

From 1995 to 2018, the Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show represented the nexus of pop culture, fashion, entertainment, camp, commerce and upbeat, all-American “sexy”.

Then, abruptly, the party was over. Toxic-workplace allegations and the MeToo reckoning cast Victoria’s Secret in a less-than-angelic light. In 2019 the show was cancelled, with many predicting that it would never return.

For five years it didn’t, save for a feature-length “Tour” film released with Amazon Prime Video last year, with limited impact. Then, in May, the company posted a video on Instagram announcing that the Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show was back.

“We’ve read the comments and heard you,” the caption read. “(The show) will reflect who we are today, plus everything you know and love.”

Next week, when VS presents its first full-scale fashion show in six years, it will try to balance on that narrow tightrope of values: seductive but not male-gazey, inclusive but traditionally feminine, culturally relevant yet never so edgy as to spook high-street shoppers – all the while attempting to retain the elements people seemed to love about the show while dispensing with the more problematic aspects. But will it be enough to reassert the brand’s cultural credibility and revive its ailing fortunes?

More fundamentally, does the show – and everything it once stood for – still belong in 2024?

Victoria’s Secret’s origin story begins with a man who felt sleazy on a shopping trip. Entrepreneur Roy Raymond went to his local department store hoping to buy lingerie for his wife, only to feel embarrassed and put off by the environment and matronly sales assistants.

He left without lingerie, but with something more valuable: an idea for a shop where men would feel comfortable and welcome to buy underwear for their partners.

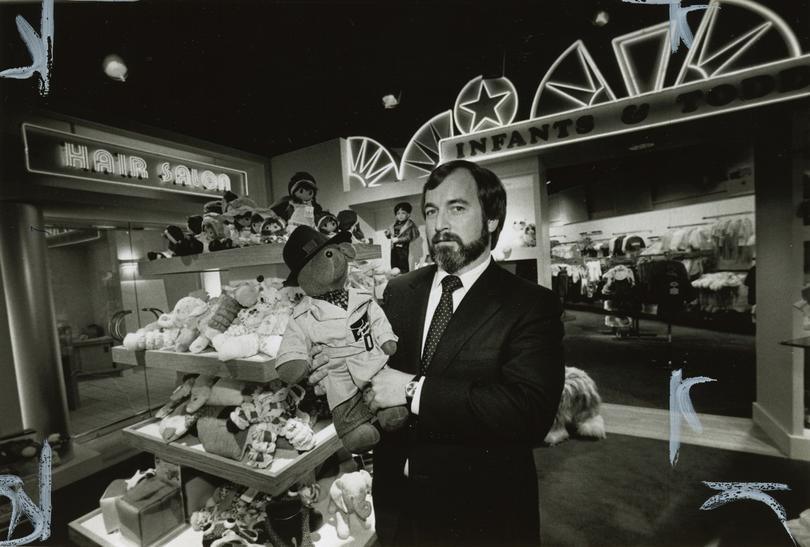

He opened the first Victoria’s Secret store with his wife, Gaye, in 1977 and quickly expanded it to five locations and a lucrative catalogue, before selling the chain to retail mogul Leslie Wexner in 1982.

That was for $US1 million; 10 years later, Wexner had grown the brand to estimated annual sales of $US1 billion. Soon it seemed there was a black-floored boudoir with hot-pink fitting rooms in every American shopping mall.

Its first fashion show was held at New York’s fabled Plaza Hotel in 1995. Over the next few years, the show grew into a cultural juggernaut, the retail world’s closest thing to the Super Bowl half-time show.

In 2011 more than 10 million people tuned in to watch models including Karlie Kloss and Miranda Kerr strut down a runway in fantastical ensembles, often incorporating gigantic sets of wings. The bigger the wings, the higher the standing of the model who wore them.

Each event promised to exceed the scale, glamour and glitz of the one before. These were showgirl-lite productions, with themed segments such as British Invasion (a King’s Guard-costumed drumline and models in pearly-queen-inspired lingerie), Aquatic Angels (seashells everywhere) and Parisian Nights (Moulin Rouge, etc). Was the show silly? Sure. It also proved a nearly bottomless well of content.

“We covered it like the Met Gala,” Chantal Fernandez, co-author of Selling Sexy, a new book about Victoria’s Secret, recalls about her time as an editor at Fashionista.com. “It was such a traffic driver.”

From model casting news (who’s in, who’s new, who gets to wear the Fantasy Bra; their exercise regimens, their beauty routines, their relationships), to the musical guests and the designs themselves, the show generated story upon story.

With its multimillion-dollar production budget, the show also represented a unique opportunity for designers. To shape its look and feel, VS hired top British stylists – Charlotte Stockdale, who has been a contributing editor at British Vogue and worked with Chanel and Lanvin, followed by Sophia Neophitou-Apostolou, the charismatic fashion editor behind 10 magazine.

They, in turn, enlisted their talented but cash-strapped fashion friends to create sculptural wings, extravagant footwear and all the other razzle-dazzle costume elements.

Designer Sophia Webster worked on the show in 2013, shortly after launching her footwear brand. “(It) was a massive opportunity and provided huge exposure,” she says. For a Fairy Tale segment in 2014, Webster created thigh-high sandal boots featuring laser-cut butterflies, one of her signature motifs.

Each pair was made according to a specific model’s calf and thigh measurements to ensure a perfect fit. “It was really special to see my brand’s emblem then being worn by the likes of Jourdan Dunn, Candice Swanepoel and Lily Donaldson… It was just so exciting.”

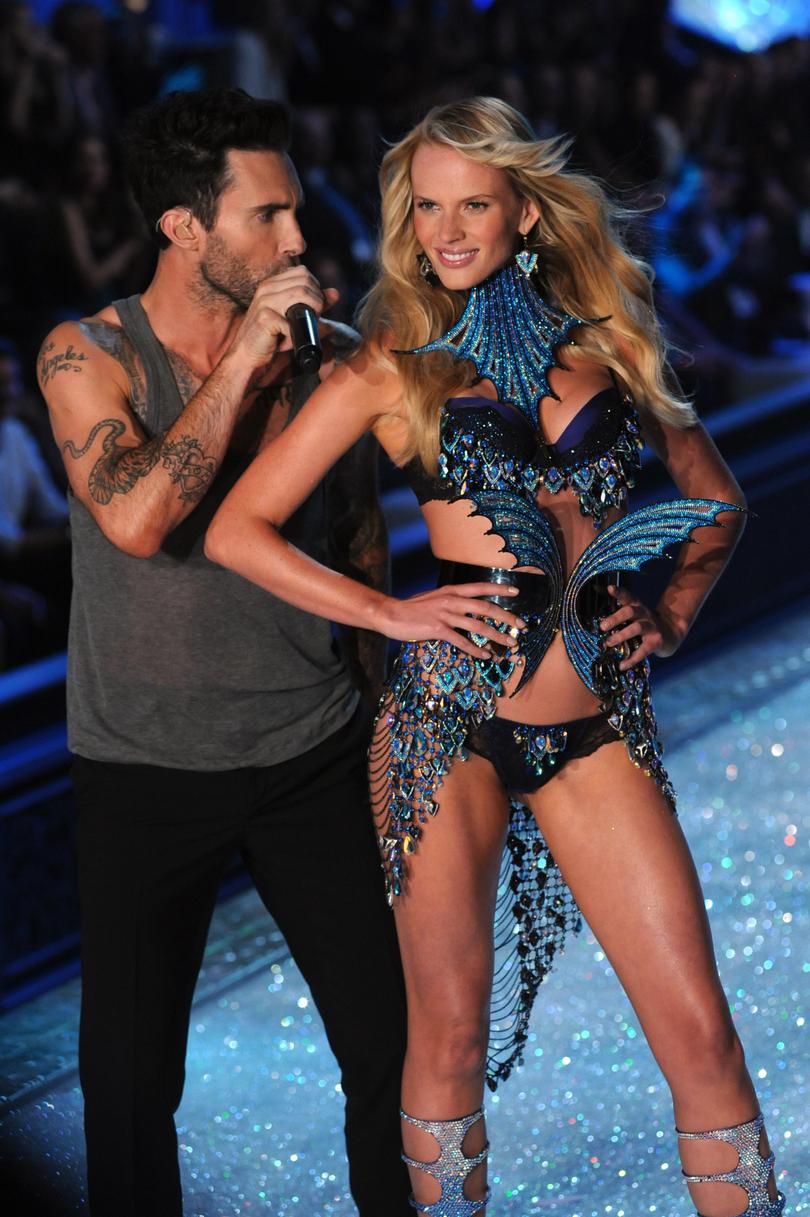

For musicians, a slot on the runway was a novel way to promote an album (or impress potential romantic partners, as in the case of Maroon 5’s Adam Levine, who was dating model Anne V when his band performed at the 2011 show; he went on to marry Behati Prinsloo, then a Victoria’s Secret Angel).

For the models, a spot in the VS show cast was more than a money job. Long before she became a supermodel, Karlie Kloss watched the show with her family. “Putting those wings on… is a moment that not many women get to experience,” she once told me. “The fact that I get to be one of those – I’ve got goosebumps. I have to keep pinching myself.”

The show’s outsized stature in American culture came down to this key element: the Angels. For a time, the toned, airbrushed aesthetic promoted by these select few official faces of the brand became the dominant American beauty ideal worldwide, “this globally recognised symbol of beauty”, Fernandez says.

“I don’t think they invented anything, but they framed it up perfectly for us and pumped it out.” Brides referenced the Angels when requesting big, bouncy blow-dries for their wedding days.

Celebrities – notably Kim Kardashian and her sisters – dressed as Angels for Halloween.

And any young woman could tap into the fantasy at her local shopping centre, with stores of affordable fluoro lace Miracle bras and diamanté thongs.

It all seemed unstoppable.

But off the runway, whispers of workplace toxicity began to bubble up several years ago. The man who was the subject of repeated complaints was top executive Ed Razek.

At the time he was chief marketing officer at L Brands, then the parent company of Victoria’s Secret, and he has been accused of multiple incidents of inappropriate conduct. Speaking on the condition of anonymity, one woman who worked there said, “I think Ed felt pretty invincible.” She claims he would appear backstage while models were naked.

Once, at a photo shoot, it is alleged that he berated a PR staffer for taking more food for lunch, telling her in front of colleagues and models, “I don’t know how you wake up in the morning and look in the mirror and you’re OK with that.”

(Razek previously declined to comment on specific allegations and told The New York Times accusations of inappropriate behaviour were “categorically untrue, misconstrued or taken out of context. I’ve been fortunate to work with countless world-class models and gifted professionals and take great pride in the mutual respect we have for each other.”)

In the wider world, beginning around 2017, women elsewhere were speaking out about power imbalances and sexual harassment they’d suffered at the hands of influential men. The MeToo movement implicated film producer Harvey Weinstein, comedian Bill Cosby and dozens of other men.

Against this backdrop, concepts like the male gaze entered the mainstream. The restrictive diets and fitness regimens models followed to discipline their bodies into show-day readiness (such as the nine-day all-liquid diet Adriana Lima described in a viral 2011 Telegraph story) started to seem rather regressive too.

Then there was the other side of the show – the audience. While the front row was often filled with celebrities, much of the rest of the audience consisted of investors and so-called friends of the brand.

“The one thing I didn’t like about the show was the crowd,” says another PR staffer who worked on the show for two years.

“Easily 80 per cent of the audience was random white men in suits” – men like the shiny-suited dude behind me at one show who, during a ballet-themed segment, panted, “I love ballerinas.”

All of which raised the question: could a brand whose tent-pole property entailed scantily clad young models parading in front of middle-aged men perhaps be a little out of touch?

Razek answered that question in a disastrous 2018 Vogue interview. Discussing diversity and the shifting lingerie market, he said: “Shouldn’t you have transsexuals in the show? No. No, I don’t think we should. Well, why not? Because the show is a fantasy. It’s a 42-minute entertainment special. That’s what it is.”

On plus-sizes: “We attempted to do a television special for plus-sizes (in 2000). No one had any interest in it, still don’t.”

Razek argued, “We market to who we sell to, and we don’t market to the whole world.” That year’s show drew a record low of 3.3 million viewers.

Razek later apologised, saying in a statement: “My remark regarding the inclusion of transgender models… came across as insensitive. I apologise. To be clear, we absolutely would cast a transgender model for the show.” But his comments had already sparked a backlash on social media. Razek resigned the following August. The 2019 fashion show was cancelled three months later.

There is a question Victoria’s Secret used to ask in its own advertising: what’s sexy now? The answer and the wider lingerie sector look markedly different than they did in 2019, when VS cancelled its live show.

Back then, Kim Kardashian’s Skims was a challenger brand with big ambitions; now it’s a $4 billion giant with smart ad campaigns that situate it at the heart of pop culture. (For a 2022 campaign, it hired retired VS Angels.)

Rihanna’s Savage X Fenty has presented shows in which pointedly diverse casts have promoted a more frankly sexual, assertive sensuality. Countless other brands, from Aerie and Parade to Dora Larsen, prioritise comfort and “real” bodies, at odds with the core VS aesthetic.

VS has ceded more than $US1.5 billion in annual sales since its 2016 peak. It reported adjusted net income of $US178 million for the fiscal year 2023, a 57 per cent drop from the year before. Shops across American malls and British high streets that once drew queues of shoppers began to look grubby, the merchandise often discounted. Some shut down. Today a mesh bra in Hollywood Pink is just £24; VS’s animal-print Cheeky Knickers are discounted online to £4.

“The profits have been eroded almost to the point of no return,” says Lauren Sherman, co-author of Selling Sexy and fashion correspondent at news website Puck. “They still sell billions of dollars worth of bras, but it’s far fewer than even five years ago.”

VS executives have spent years making an apology tour of sorts. In 2021, Victoria’s Secret split from L Brands and spun out as a standalone company with a majority-women board. They replaced the Angels with the VS Collective, a group of “partners” including US football star Megan Rapinoe and actor-entrepreneur Priyanka Chopra Jonas. Last year they presented Victoria’s Secret The Tour ’23 on Amazon Prime Video. It failed to make much of an impact.

A new CEO joined in September – Hillary Super, previously chief executive at Savage X Fenty.

This summer, the brand tapped the Marchioness of Bath, Emma Thynn, as the face of Daring, its new fragrance. She appears in the campaign wearing a pair of golden wings and a corseted gown – not skimpy underwear.

The 2024 show is being teased as the comeback. Models including Gigi Hadid, Candice Swanepoel and Taylor Hill will return – as will Tyra Banks, an original Angel who last walked the VS runway in 2005.

In a signal of VS’s revamped approach, two models joining the cast for the first time are Paloma Elsesser and Devyn Garcia, both of whom are considered curvy, by industry standards.

“The transportative, fantasy element of what they did in their shows was what made them really special,” says Sophia Webster. “I hope they don’t lose that. If they take a more inclusive direction, then that allows for more people to see themselves in the story that they’re trying to tell.”

Along with more diverse body types, the first live show in six years will feature the first all-woman entertainment line-up, led by Cher. Styling it all is Emmanuelle Alt, the former editor of French Vogue.

Alt has styled a number of VS campaigns of late – including one shot at Longleat House, the stately home of the Marquess and Marchioness of Bath – cultivating an aesthetic best described as classic Victoria’s Secret.

“She’s an amazing runway-show stylist, she’s very commercial and she has great taste, so it makes a lot of sense to me,” Sherman says.

Fernandez agrees: “There’s a French view of sexuality that’s more refined. If you’re trying to avoid looking like the Miss America pageant, then bringing in a non-American can help that, because they’re coming to it from such a different perspective of sexuality.”

So far, so strategic – but Victoria’s Secret still has a narrow path to navigate if the brand is to return to its past prominence. And one thing is clear: today’s viewers are no longer as likely to accept simplistic messaging that suggests walking a runway nearly nude is tantamount to empowerment.

“It’s a tricky thing to do: how do you create a lingerie fashion show in 2024 that doesn’t feel misogynistic? I do not envy that assignment,” Fernandez says. “They’re only going to have so many chances to reassert themselves publicly,” she continues, “so the pressure is on for them to really make a statement with this.”

The implicit promise of the Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show back in its heyday was that any woman could feel like an Angel – if only she tried hard enough and bought the right bra.

But what women want today isn’t necessarily the same. For many it’s to feel secure or alluring or supported or seductive or comfortable or just plain hot in their lingerie, on their own terms.

The thing about culture is that it moves on. And the thing about bras is that no matter what the tags say, they can’t work miracles after all.