The definitive guide to getting your adult kids to move out

Discussing financial independence and moving out should start long before kids turn 18 or feel unwelcome in the family home.

The other day, I caught some of comedian John Bishop’s new material for his 25th anniversary UK tour on Radio 4, and he chuckled about how uncomfortable he feels having two adult children living at home with the combined age of 58 and one with a beard.

Of course, comedy often works best if you can relate to the joke – and John Bishop is on to something.

Today, one in four adult children (4.9 million) live with their parents in the family home. It’s a figure that’s risen by almost 15 pc since the 2011 Census, with disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and rising property and rental prices contributing factors. The average age for those living at home is 24 and 25 in London.

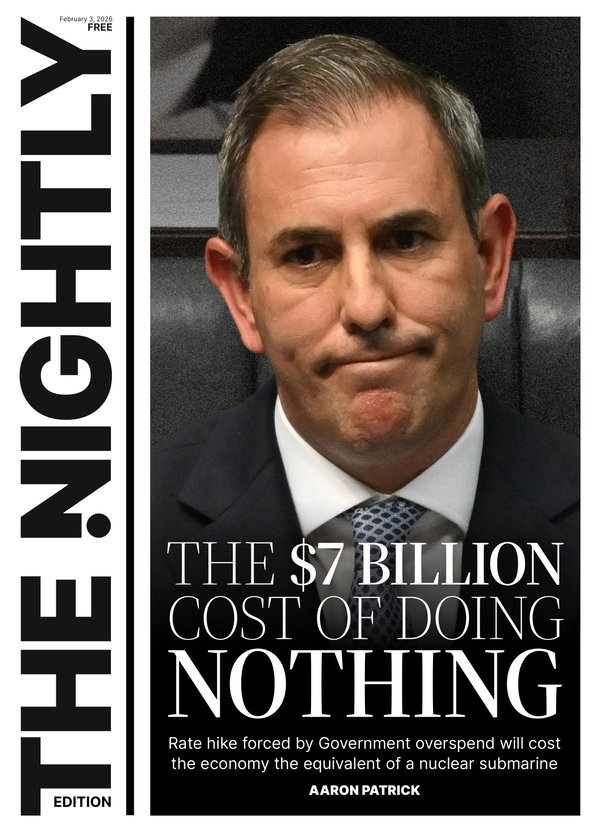

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.It remains a great parental challenge to know when, and how, to give your children the push they need towards leaving home and to financial independence.

The subject of how you strike the right balance between protecting and overprotecting, between supporting or spoiling children comes up often in my practice.

Some parents tell me of their fears of pushing too hard for their children to fly the nest and being thought of as heartless. Some take it as a compliment that their kids like living with them. Others express guilt that their child is not ready to go.

The reality is, teaching your child to stand on their own two feet is the greatest gift you can give them – and is in everyone’s best interest in the long-term.

So when adult children are failing to move out, it’s time to ask two questions: how can you equip them with the skills they need, and what can you do to make moving out feel like the next step rather than a giant (and unwanted) leap?

These are my tips for parents.

START CONVERSATIONS WHEN THEY’RE YOUNG

Chats about financial independence and the transition out of the family home shouldn’t be left to when they turn 18 or when they have overstayed their welcome.

Start a couple of years earlier, setting the scene by having conversations about what they want from life, where they see themselves in the next five years, what you expect should happen and their fears about being independent.

These conversations will give them time to equip themselves with the right skills and to process (with your support) mixed feelings about the transition.

GIVE THEM POCKET MONEY

Children can learn a lot about money management and saving from being given pocket money and later an allowance from as young as seven or eight.

They learn how to make money choices and mistakes from an early age and get used to what it feels like to overspend and regret it, or to save and feel pride in buying a big toy with their own money.

These valuable lessons will shape their behaviour as they enter adulthood and make the same choices on a larger scale.

DON’T LET EXCUSES LINGER

Focus on why your child is still living in the family home. There could be practical reasons – such as student debt, unemployment, or lack of savings – that make the idea of moving out seem impossible. It’s important to work out whether these obstacles are genuine, and if your children are trying to remove them, or whether they are being used as excuses.

Have an open conversation. Start with gentle, non-judgmental questions. Ask: ‘Why do you think it’s taking so long to take the next step? What’s stopping you?’

Specific questions can follow: ‘Do you have a plan? Do you have savings? How many jobs did you apply for this month?’

The aim is not to criticise but to create a safe space where they can voice their concerns. Some children might fear independence, feeling lonely or be anxious they won’t cope. One of my clients confessed to financial self-sabotage; spending their allowance so they never had enough savings to leave. It was, in part, because it made him feel cared for and looked after.

Rather than dismiss any concerns, help them think of ways in which they can feel less anxious.

How can you still feel connected as a family after they move out? What skills would help them feel more confident about ‘looking after themselves?’

I have heard from many adult children living at home that they don’t feel like a ‘proper adult’ when it comes to money.

Their response may be that the main reason they want to stay at home is because it’s easy, cheap and comfortable, and moving out will take energy.

If this is the case, you must communicate your desire to establish new boundaries because you feel it is best for all.

IF THEY ARE SAVING FOR A PLACE . . .

Your child might have told you they want to live at home to save money for a property. If your objective is to get them to be financially independent, conceding a free ride won’t be the best way to enable that.

Instead, establish boundaries and make demands. It could be that you ask them to pay you rent, or you ask them to provide a savings plan with dates and amounts.

If you ask them for rent, it could be a nominal amount that leaves them enough income to save.

You are also entitled to refuse to accommodate them. In which case, you will have to explain the reasons why you think it’s important they move out.

You can express ways in which you might be able to help – should you wish to do so – such as brainstorming other revenue streams.

ARE YOU HOLDING THEM BACK?

Are you still doing their laundry? Cooking their meals? If so, it’s no wonder they’re reluctant to leave.

If they are being infantilised, then it is unlikely they will have much drive to change their situation. They will also struggle to view themselves as capable adults.

Research shows that children who do chores are more successful as adults because they learn to have a work ethic.

Even if they are unemployed, give them an allowance to manage, which will help them learn to make financial decisions.

Suggest apps that can help them categorise their spending such as Emma and RiseUp. Some banks also offer these tools, including Starling or Monzo. This is better than them seeing the Bank of Mum and Dad as an unlimited cash machine.

Set the allowance at a level where it isn’t so comfortable that moving out and getting a job feels like a downgrade.

As the parent of an adult child still living at home, you might actually enjoy being the caretaker, as it gives you a sense of purpose. A part of you might feel that you are setting them free but another might feel abandoned by them.

If you don’t work through these feelings ahead of time, they may get picked up on by your child, who might feel guilty about leaving home. Think of ways in which you might address your loneliness before they leave.

Unless you begin to treat them as an adult who can survive on their own, your offspring will struggle to see themselves doing so, too.

MY PLAN . . . Set clear boundaries

ONCE you’ve understood the reasons behind their reluctance to move out, it’s time to set some firm boundaries. Comfort can be a trap. It’s crucial to make the family home a place where they contribute rather than somewhere they get a free ride.

Start by setting clear expectations: which household chores will they take responsibility for? Should they contribute to rent or bills, even in a small way? Charging your child a modest rent, even if they’re receiving an allowance, can help them get used to budgeting and managing money.

Plus, it shifts their mindset – if they can pay rent at home, they’ll be ready to pay rent elsewhere.

Make it clear what you’re willing to keep paying for and what will stop. Will you still cover their phone bills? Clothes? Internet? Spell it out, and if necessary, put it in writing. It might seem harsh, but boundaries create the framework for healthy independence.

Reassure them that this isn’t about getting rid of them but helping them become independent.

For example, you could say you’ll still invite them on family holidays (and you might even offer to pay for them), but your acts of generosity from here on should not be an expectation.

Offer support

REMIND them your goal is to see them prosper – not to get rid of them – and you want to help them do that.

Helping them build financial skills in a safe environment is the best way to achieve this. You could have a conversation about budgeting, saving and managing debt.

Financial management is not an innate skill, and your desire or willingness to offer help might provide them with much-needed information. Share how you do it.

Help them think of new ways to look for a job and new housing options – have they considered a flat-share or being a lodger? If they are employed, have they thought of asking for a pay rise or a promotion? The conversation with you should show them that they have options.

Don’t rush to the rescue

If they still come asking for money, do not rush to the rescue. Instead of offering handouts, ask them how they plan to solve the problem. They might have managed to leave the family home, but, at the first setback, they ask to return ‘just for a while until I find another job’.

There is no right answer here, but a ‘yes, of course’ is the wrong one. If you do agree to help, this needs to be done after you have encouraged them to think through options.

Maybe couch-surfing or taking up a job they consider ‘beneath them’ might give them the motivation to speed up the job search.

Let them know that compromises and disappointments are part of the process of job and flat-hunting, and that financial mistakes are part of that, too. Reassure them that they are capable of overcoming these hurdles.

Gradual changes

CHANGE will not happen overnight. Phase out allowances, gradually stop paying for some expenses and work together to create a moving-out plan. Setting a timeline can help your child see moving out as a goal.

There are books that may help you, too, such as Failure to Launch: Why Your Twentysomething Hasn’t Grown Up...And What to Do About It, by Mark McConville; and The Opposite Of Spoiled, by Ron Lieber.

Negotiating the transition from family life to full independence with empathy and firm boundaries can help you preserve a good relationship with your grown-up children while also empowering them with the confidence they need to thrive.