MARK RILEY: Labor’s cost-of-living plan settles a long-running debate. Our inflation problem is homegrown

MARK RILEY: Labor’s plan to tackle cost-of-living settles a long-running debate. Our inflation problem is indeed homegrown.

In the rush of analysis of Tuesday’s Federal Budget, one significant point has been overlooked.

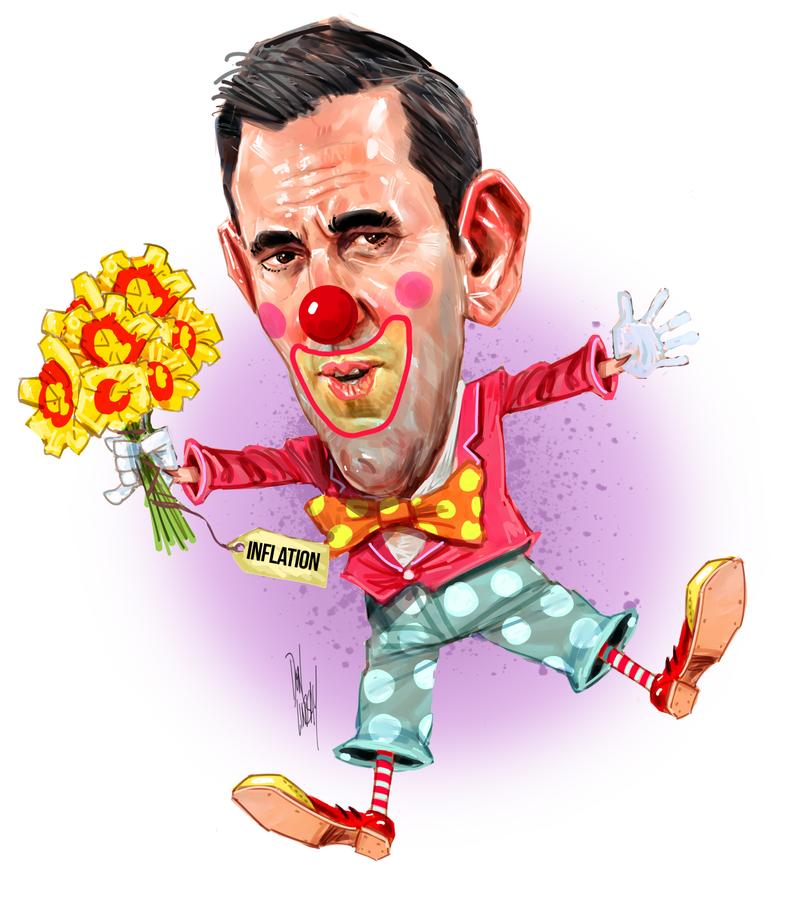

The Budget finally settles a major debate that has been thrashing around in the central ring of the political circus since late last year.

The design and marketing of the Budget’s central plan to bring down the cost of living over the next seven months to Christmas delivers the answer beyond doubt.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Australia’s inflation problem is indeed homegrown.

It is clear in the fact that Treasurer Jim Chalmers’ solution to that problem is itself entirely homegrown.

The main targets of his $7.8 billion plan are all homegrown drivers of inflation — the retail cost of energy, medicines and rents.

It is true that the base costs of these items are largely set in the global marketplace, but the wide variations in the retail prices between countries is a result of domestic economic settings.

Chalmers’ solution is all about reducing those domestic influences through direct subsidies and price caps.

It is a homegrown solution to a homegrown problem.

This Budget finally settles the debate sparked when Michele Bullock observed at a dinner for business economists in November, soon after taking over as Reserve Bank governor, that the remaining inflation challenge ahead of her was homegrown and demand-driven.

That was an inconvenient observation for a Government that was pointing to international supply chain disruptions, spiking oil prices and wars in the Middle East and Eastern Europe as primary sources of inflationary pressures.

Chalmers’ fiscal approach to this problem could appear to be based on a colossal contradiction.

Jim Chalmers is spending to bring down inflation.

Economists have described it as an attempt to “buy” a lower inflation rate.

Chalmers demurred when I put this to him this week.

He wouldn’t put it that way.

But it does appear to be what he is doing.

Cutting energy bills, freezing the price of PBS medicines and decreasing rents through higher Commonwealth assistance directly attack three of the major items that go into the consumer price index basket.

It is the change in prices of those items that the Australian Bureau of Statistics uses each quarter to calculate the official rate of inflation.

If the aggregate cost of those goods goes down, inflation goes down. If the cost goes up, so does inflation.

And, as all homeowners know to their great lament, when inflation goes up then interest rates and mortgage repayments often follow.

Chalmers’ plan is to break that cycle at its source by holding prices down.\

The Budget predicts that his new cost-of-living plan will cut inflation by half a per cent over the next financial year.

The reduction would be even deeper when coupled with the impact of existing measures, such as cheaper childcare, fee-free TAFE and increased rates of Medicare bulk billing.

Official inflation was at 3.6 per cent in the March quarter.

That means a reduction of just over 0.6 per cent would take it back within the RBA’s target range of between 2 and 3 per cent, triggering interest rate cuts and a declaration that the inflation dragon had finally been tamed.

Inflation, though, has recently proven to be “sticky”.

That is, its sharp decline from a high of 7.8 per cent in December 2022 has begun to flatline.

Indeed, before the Budget the Reserve Bank was predicting it to tick back up to 3.8 per cent by the end of the year.

The crucial question is what the RBA’s prediction for inflation will be now.

There are many caveats attached to the Budget’s suggestion that the official rate could fall back below 3 per cent before Christmas.

But the world of politics has little regard for such subtleties.

In political terms, a suggestion is as good as a rolled gold promise.

And this is one whose veracity will be determined in short order.

Anthony Albanese confirmed on Seven’s Sunrise on Wednesday what this column has been predicting for the past year.

He is planning to bring next year’s Federal Budget forward to March to allow himself the option of a May election.

That gives Jim Chalmers a year to prove that his cost-of-living gamble was worth it.

If inflation does fall below 3 per cent by the end of the year and there are interest rate cuts before the expected election in May, he will become a Labor hero.

And if that doesn’t happen, he and the Albanese Government might get a big fat zero from the most powerful of homegrown influences — the Australian voting public.