PAUL MURRAY: Hiring out Chris Bowen may be Anthony Albanese’s biggest political misjudgement since the Voice

Paul Murray: Anyone who has watched Chris Bowen’s career over the past 20 years could hardly say that diplomacy is his strong suit. He’s graceless.

Anthony Albanese’s compliance in hiring out his beleaguered Energy and Climate Change Minister to the United Nations for the next 12 months is pretty strong evidence that Labor is unworried by the Opposition’s ditching of a bipartisan net zero by 2050 policy.

That may be Albanese’s biggest political misjudgement since calling the Voice referendum, another hubristic indulgence.

Why the Prime Minister would want to inflict someone so obviously struggling with his portfolios on the UN’s byzantine emissions reduction process is open to many interpretations.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.The least believable explanation is that offered by Foreign Affairs Minister Penny Wong, one of Labor’s most practised twisters.

Wong says that Chris Bowen’s role chairing next year’s COP 31 climate change conference – a sop for this country failing in its bid to host the talkfest at a prospective cost of $2 billion – would “give Australia and the Pacific unprecedented influence over multilateral deliberations and actions of the global community in 2026.”

The idea that the COP presidency is influential is worth exploring. As is the effect Bowen’s commitment to the job will have on Labor’s faltering renewables transition program – and our skyrocketing electricity prices.

The last person to come out of a COP presidency smelling of roses was Laurent Fabius, then French foreign minister and a former PM, who steered the 2015 Paris agreement in a masterclass of diplomacy.

Anyone who has watched Bowen’s career over the past 20 years, especially his underwhelming performances as a minister, could hardly say that diplomacy is his strong suit. He’s graceless.

Who could forget his undiplomatic moment during the 2019 election campaign when he said, as shadow treasurer: “If you don’t like our policies, don’t vote for us.”

A big number of Australians took up his offer and Labor lost the “unloseable” election.

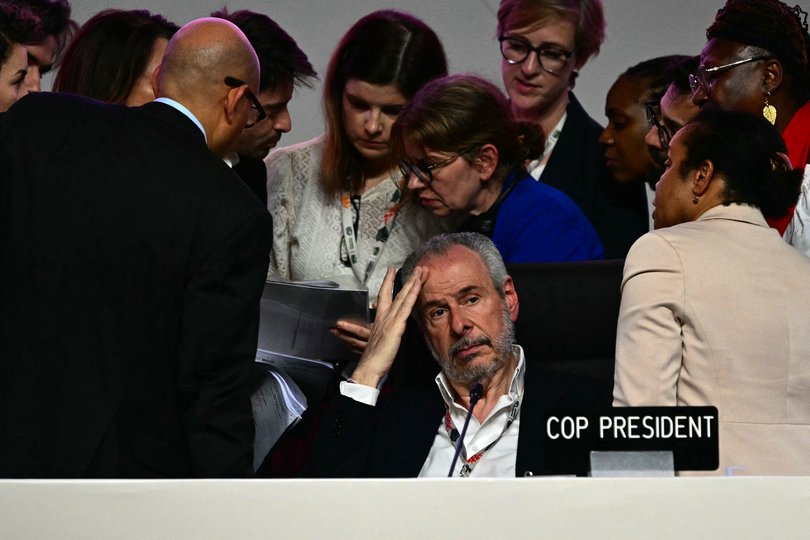

The most recent person in the role that Bowen has assumed was Brazilian diplomat Andre Correa do Lago, who achieved very little at the recently-concluded COP30 in Belem.

The previous four presidents of the conference were Azerbaijan Minister of Ecology and Natural Resource Mukhtar Babayev, United Arab Emirates Minister of Industry and Advanced Technology Sultan Al Jaber, Egypt’s Minister of Foreign Affairs Sameh Shoukry and the United Kingdom’s Alok Sharma.

Hardly household names internationally. They all presided over COPs of limited achievements, with some complete flops, particularly in terms of demands for strong action against fossil fuels. Note that three came from significant oil-producing countries.

Albanese said under pressure in Parliament this week that Bowen would not have to engage fully with his new position until much closer to the event, due around the end of next year.

“I don’t know if those opposite have participated much in international forums but … the crunch point of negotiations comes at the end,” the Prime Minister said, attempting to downplay the demands of Bowen’s job-sharing arrangements.

Correa do Lago was appointed on January 21 and stood down as Brazil’s vice‑minister for climate, energy and environment at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs the next day to work full time on the job.

He started calling meetings in March and was engaged in extensive global briefings by September.

Sharma stood down as a secretary of state in Boris Johnston’s conservative Government in January 2021 to concentrate on the COP26 presidency, but that didn’t stop the conference falling far short of expectations with weak language on phasing out coal and massive shortfalls in climate financing promises.

“May I just say to all delegates I apologise for the way this process has unfolded and I am deeply sorry,” Sharma said in closing the conference. He has since been pensioned off to the House of Lords, but such a sinecure is unlikely to present to Bowen.

So what does Albanese hope to achieve from Bowen remaining in his Government’s most contentious Cabinet post while negotiating the next COP presidency?

Given the mounting pressure from green activists on phasing out all fossil fuels, Bowen will be a substantial target because of Australia’s massive exports of coal and gas, earning us around $120b annually.

How will Bowen hope to assuage those countries that tried to disrupt the conference in Brazil because it was going soft on fossil fuels?

More than 30 nations, including several from the Pacific, loudly opposed Correa do Lago’s draft communique which contained no mention of oil, coal or gas.

Keep in mind that Brazil is the biggest oil producer in South America. After Colombia and Ecuador walked out over the first draft, Correa do Lago had to close the session before the protest grew.

More than 80 of the 193 national delegations pushed for a roadmap to end the use of coal, oil, and gas, but the final text avoided binding commitments or the term “phase out”.

According to Agence France Presse, a negotiator who wished to remain anonymous said China, India, Saudi Arabia, Nigeria, and Russia rejected it outright.

The final communique only referenced the earlier “UAE Consensus” from COP28, which called for a general “transition away from fossil fuels” without binding timelines.

In another failure, a planned $125b forest protection fund shrank to about $6b in pledges, undermining Brazil’s Amazon‑focused agenda.

All of these pressures will have intensified by the time Bowen gets in the chair at COP31, this time championing Pacific Islands, while hoping the world ignores Australia’s economic dependency on fossil fuel exports.

Good luck with that.

Meanwhile, the centrepiece of Bowen’s plan for Australia to achieve net zero by 2050 – his so-called Capacity Investment Scheme – is floundering.

Its success is essential for Bowen to get to his target of 82 per cent renewable energy by 2030, which experts say is wildly unachievable, but which Labor has yet to concede.

Throughout next year Bowen really needs to be at home and turning around what looks like an ignominious failure. But he won’t be.

Two informed articles this month on the pro-renewables website, Renew Economy, highlight the enormous issues facing Bowen’s policy centrepiece.

“The Capacity Investment Scheme was set up to accelerate the build-out of renewable energy by using auctions for underwriting contracts to enable 26 GW of renewables and 14 GW of dispatchable capacity by 2030,” wrote Associate Professor Chris Briggs, from the Institute for Sustainable Futures at the University of Technology Sydney.

“Whilst battery storage projects are booming, only a handful of solar and wind projects successful in CIS tenders have subsequently reached financial close and proceeded to construction.”

Briggs avoids saying why battery projects are highly favoured by investors in his focus on the CIS failure to advance wind and solar generating capacity.

The reason is that batteries are where the sharp money is being made. Battery power is about the most expensive in Australia’s auction-based electricity systems because it is drawn on at times of highest demand, thus getting the highest price.

But batteries don’t produce power. They just store it. They plug holes, but they cannot meet the baseload demands of Bowen’s 2030 target – or go anywhere near getting to 2050 with a reliable, affordable power system.

“Market participants report competition between projects has led to prices being awarded by the CIS that are not sufficient for projects to satisfy debt funders and reach financial closure – which means they require a power purchase agreement with a retailer (a ‘utility PPA’) or an electricity buyer (a ‘corporate PPA’),” Briggs says.

“As retailers have signed very few PPAs with new solar and wind projects in recent years, a lot of weight is effectively being placed on the Corporate PPA sector to fill the gap.”

Briggs says 6GW of wind and solar are needed annually to meet the 2030 target, but corporate PPAs attracted only 1 to 1.5GW.

Energy analyst David Leitch wrote that the CIS “will be a failure” if it does not achieve 82 per cent renewables by 2030: “At this particular moment the CIS is looking like a paper tiger, a typical example of the road to hell being paved with good intentions.”

Leitch says a major failing with the CIS – which replaced the Renewable Energy Target, started by the Howard coalition Government in 2001 and expanded by the Rudd Labor Government – is that unlike its predecessor, it does not create demand.

“It turns out this really matters,” Leitch says. “The CIS leaves all the onus on suppliers to take the risk of building. Gentailers can, and they do, sit on their hands.”

And he says weak disclosure and limited transparency have undermined investor confidence in CIS.

“When you are flying high and results are fantastic investors will overlook many things,” he wrote. “When things turn sour and friends are hard to find then good disclosure, diligence and efficiency become a lot more important. The Government, though, seems to regard disclosure as bad.”

The dogs are barking that Bowen’s strategy is failing. Hence the secrecy.

The new COP president’s biggest problems are right here at home, but his ambitions are decidedly international. Trouble ahead.