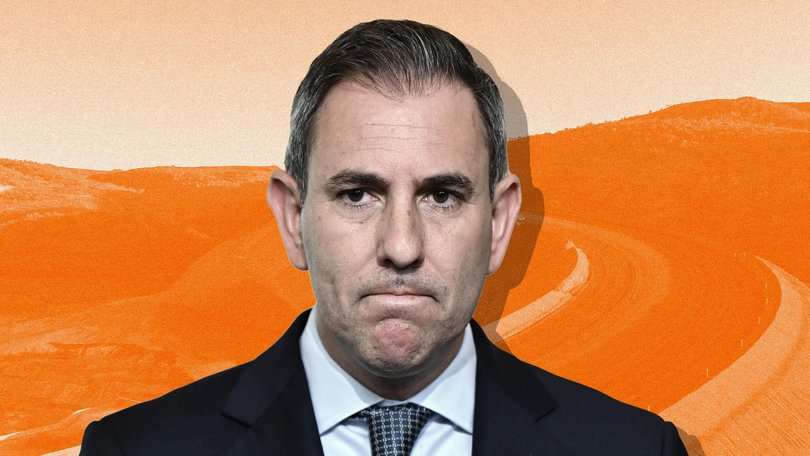

PAUL MURRAY: Jim Chalmers’ relentless economic spin is insulting Australian families

We’re all tired of Jim Chalmers flashing a schoolboy grin while he throws out excuses in an attempt to avoid responsibility for the harm his economic policies are causing.

Are you tired of Jim Chalmers yet?

Tired of his excuses for the economic harm his policies are causing? Tired of his relentless political spin?

Tired of his lack of ability to bring about tax, spending and productivity reforms despite Labor’s massive parliamentary majority?

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Tired of the schoolboy grin/grimace as he shares your pain? Time and again.

These are not just questions aimed at Australian voters and mortgage payers, stung this week by the first of a new round of interest rate increases which can be directly sheeted home to Chalmers’ incompetence as Treasurer.

They’re also for the Canberra press gallery which, to coin a phrase, has given Chalmers more than enough rope. Time’s up.

The Reserve Bank now expects inflation to stay outside its target band for at least another year, invoking further rate increases, a perfect pigeon pair of economic failures with Chalmers’ predicted 10-years of Budget deficits.

In every comparable country, the inflation that took off after the pandemic is under control, well below our 3.8 per cent, most at the lower end of the RBA’s chartered 2-3 per cent band.

Not so in Australia. Why?

The answer in large part is Chalmers.

Let’s join the dots, a necessary process that so many in Canberra are reluctant to undertake.

It is now obvious that the Reserve Bank’s decision to cut interest rates on February 18, just before the federal election, was misjudged. It was the first of three RBA reductions that Chalmers brags about and ridiculously uses to mount an argument that they prove inflation was under control last year.

They prove the opposite.

Those rises could not kill it off because governments around Australia — led by Labor in Canberra and WA — were over-spending against the RBA’s measures.

Only an economic nincompoop would say that record levels of government spending would not be a significant contributor to inflation.

But that’s Chalmers.

Leading economists lined up this week to attest that he was wrong. And to say the RBA cuts last year were misjudged.

RBA governor Michele Bullock deserves criticism for moving on interest rates too early — just before an election, allowing Chalmers to claim political credit — and then too late.

Both times, it’s open to conjecture that politics played a part.

The pre-election decision was the first taken by Chalmers’ restructured RBA. Didn’t that go well?

Chalmers this week was grasping at straws claiming that there was nothing in the RBA’s statement about government spending, so therefore it couldn’t have been an issue.

Surely he is aware of the Governor’s previous comments on this matter. At a Senate hearing last November, Bullock rejected suggestions she had cautioned the federal government about its spending behaviour.

“I don’t believe I’ve been cautioning anyone,” she said.

“My reading — when I speak privately to the Treasurer and when I hear him speak on television and radio — is that he’s fully aware of the inflationary implications of his own policies.

“He needs to be thinking about that. Because he — like me — understands that inflation is really what’s hurting people at the moment.”

How very diplomatic.

She went further after this week’s decision in a perverse interpretation of the RBA’s “independence” when asked about high government spending: “That’s not my business.”

So no responsibility to inform public know what’s really happening rather than have us rely on the BS we get from politicians?

That’s not independence.

Perhaps Bullock doesn’t want to finish up like her predecessor, Philip Lowe, who was run out of the job on a rail by Chalmers as the blackguarded scapegoat for crucial interest rate rises to deal with a surge in post-pandemic inflation.

Under Lowe, the cash rate jumped from 0.10 per cent to 4.10 per cent in just over a year. This week, the RBA lifted the rate from 3.6 to 3.85 and it’s likely to pass Lowe’s 4.1 benchmark later this year.

Given the RBA’s latest reasoning, Bullock’s comments in November, responding to WA Liberal senator Dean Smith, are illuminating.

“In recent days, you’ve expressed a note of caution to policymakers in regards to their spending appetites as they come to end-of-financial-year statements and election periods,” Senator Smith said. “Can you just elaborate for the committee what are some of those risks if policymakers don’t exercise a more prudent approach to government spending?”

Bullock: “What I’ve been observing is that the private sector in Australia at the moment is very weak, and the public sector demand has been filling that gap, so what we have is an economy which is not growing very quickly and the private sector’s very weak and the public sector’s providing some support.

“Our forecasts show that with that sort of mix, we end up with inflation coming back down to target in the next couple of years. Now, it’s true that total demand is what is driving inflation, in terms of total demand versus total supply, so that’s a mix of public and private.”

This week, the bank’s main reason for raising rates was that private demand was too strong. Not “very weak” after all. Three months later.

In other words, the RBA got it badly wrong — again — last year.

Bullock finally, grudgingly, conceded high government spending contributed to inflation under persistent questioning at another parliamentary hearing yesterday.

One of the loudest voices cautioning against the interest rate cut last February was Judo Bank economist Warren Hogan. At the time, Hogan argued inflation was still too high, underlying domestic pressures hadn’t eased enough and cutting risked re-accelerating inflation.

In May, after the second rate cut, Hogan told Yahoo Finance the RBA was “taking a risk” by cutting rates while inflation pressures remained elevated and that the February cut was based on overly optimistic forecasts.

Hogan warned the RBA was misreading the strength of the economy and had underestimated private demand, services inflation and the persistence of domestic price pressures.

He said the RBA risked “stalling” the disinflation process, having to reverse course later and undermining its own credibility.

Which is exactly what happened.

But Hogan went even further, opening up debate about Chalmers’ new RBA structure, especially the new Monetary Policy Board. He suggested it lacked the experience to judge inflation risk, had been too eager to demonstrate independence and relied too heavily on models.

All of that must be sheeted home to Chalmers who took full ownership of the new structure.

Hogan’s predictions this week revisited last year’s mistakes: “Unfortunately, that means that we’re probably going to have to reverse all of the rate cuts from last year and there’s a very real risk that they’ll have to do even more. I put forward the simple proposition, if a 4.35 per cent cash rate in 2024 did not get inflation under control, why would we think that it’s going to do that in 2026?”

And Hogan is particularly clear-eyed about government spending.

He told Sky News government spending is “too expansionary” for a capacity-constrained economy, fiscal policy is “working against the RBA” and that public-sector wage growth and infrastructure spending are inflationary.

Hogan has argued that the inflation pickup in the second half of 2025 was not just a monetary-policy issue. It was also driven by NDIS-related demand and State-level capital programs, all contributing to “fiscal expansion in a hot economy.”

The penny finally appears to be dropping in Canberra.

As The Nightly reported this week, journalists peppered Bullock at her press conference with questions about whether the board was being pressured not to criticise the Labor government for contributing to inflation.

“I’d like to know has anyone in the Albanese Government told you, or anyone in the RBA to your knowledge, not to comment on their spending?” asked one journalist.

“No one has made that comment to me,” she answered. “And the board, obviously, makes its decisions independently of the government.”

Does it? The three senior members of the board are government officials and the other six were all hand-picked by Chalmers.

Meanwhile, the Opposition fails spectacularly to land a blow on Labor while it thrashes around in its own self-inflicted inconsequence.

The Liberals put out an email last week pointing out the Government had been caught trying to hide a nearly $60 billion black hole with new figures from the Budget update in December revealing deficits from 2029–30 to 2035–36 were that much worse than expected.

They said that since Labor was elected in 2022, the cost of food is up 16 per cent, education 17 per cent, health 18 per cent, rents 22 per cent, electricity 38 per cent and insurance 39 per cent.

And then they went back to war with their former coalition partners and among themselves, further betraying not only their conservative supporters, but a nation in need of a strong Opposition.

Chalmers just laughed at them.

And went back to wrecking the economy.