AARON PATRICK: Bill Shorten couldn’t shake ruthless reputation he forged in the Julia Gillard-Kevin Rudd era

AARON PATRICK: Shorten battled a reputation as a schemer who couldn’t be trusted; an assassin waiting to bring down another prime minister.

In past months, according to a person who knows him, an unusual calm settled over Bill Shorten. The Victorian politician’s trademark aggression had subsided. He no longer complained about the criticism that had shadowed him for years: that he was a schemer who couldn’t be trusted; an assassin waiting to bring down another prime minister.

By foreshadowing his political retirement on Thursday, Shorten acknowledged publicly what has been obvious to the political world for years: the NDIS minister would never grasp the job that had consumed him since he had walked into the Monash University ALP Club as a first-year law student with a cutting tongue and a chip on his shoulder.

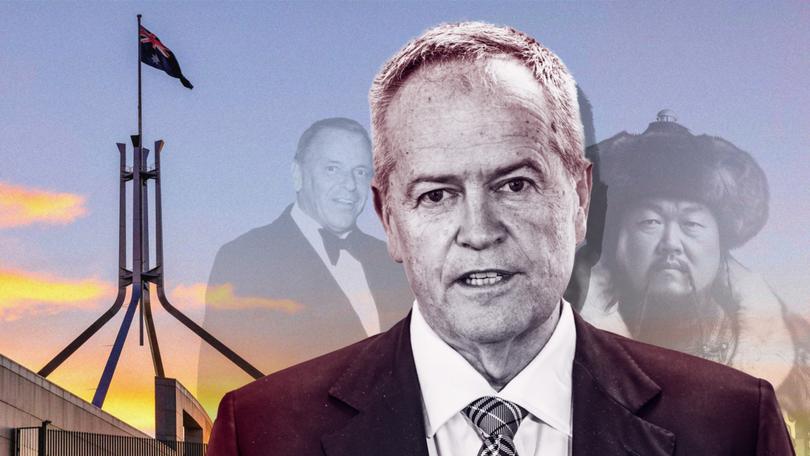

Shorten’s self belief made him a natural leader, and he stormed the Victorian Labor Party in his twenties like Genghis Khan conquering Eurasia. His hero was Bob Hawke, politically and personally. Like Hawke, he wanted to be loved by the working class and celebrated by the business elite.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.He achieved some success at both. His famous appearance at the 2006 Beaconsfield mine rescue of Todd Russell and Brant Webb was only possible because a billionaire who employed his members, Richard Pratt, loaned the young union leader a private jet to get to Tasmania in time for the live news coverage.

Pratt, who liked having politicians in his pocket, was a member of a small group of rich Melburnians who thought Shorten would make a terrific ally in the Lodge. He took Shorten and Beale on international trips in in the jet, including to Cuba, according to the businessman’s widow, Jeanne Pratt.

Shorten’s failure to become prime minister was due to personality not effort.

Decades courting attention – Shorten has always seen himself as a skilled media manipulator – seemed to have backfired. The public knew him well, and didn’t trust what they saw.

The Australian National University’s long-running, credible elections survey found Shorten was rated inferior, in the two elections he lost, to then Liberal prime ministers Malcolm Turnbull and Scott Morrison on eight out of nine character traits. He got the lowest score for inspiring leadership, at 21 per cent, in the study’s history.

The day after Anthony Albanese won power in 2022, one of Shorten’s close parliamentary allies me he was lobbying for the foreign affairs portfolio.

Shorten denied making a grab for Penny Wong’s job, but it was easy to see how the man who celebrated his engagement at the Pratts’ Melbourne mansion (he would leave his wife, Deborah Beale, after they failed to conceive) would have preferred mixing with diplomats in the great halls of state than downtrodden families of the disabled in suburban Australia.

Albanese’s decision to assign Shorten the National Disability Insurance Scheme was an act of political genius, or cynicism. As one the main lobbyists behind the much-abused and financially unsustainable welfare program, Shorten couldn’t refuse the job. At the same time, denying services to struggling Australian families – as the stretched budget requires him to do – wasn’t a great way to rebuild enough popularity to run for leader again.

On Thursday, as he gave a retirement speech next to the prime minister, Shorten demonstrated his strength as a political communicator. He quoted Frank Sinatra, the type of handsome rogue Shorten would love to be associated with.

Sinatra sang “I did it my way”.

Shorten lived those words, and had a big effect on politics.

His ruthless approach within the Labor Party contributed to a multi-decade cycle of shifting factional alliances in the Victorian division with no ideological or ethical foundations. Shorten’s own right-wing faction – which put Hawke in Parliament, changing the nation’s trajectory -- came to rely for power on the CFMEU, a union so obviously morally bankrupt that the Albanese government won’t allow it to represent its own members.

Shorten’s failure in the 2019 election, after proposing modest policy changes, made it harder for future Labor leaders to ask voters to approve change. The once-bold party became timid.

His role in the removal of Kevin Rudd and Julia Gillard as prime ministers in 2010 and 2013 damaged the party’s image. It exposed the self-interested nature of politics to a shocked public, and therefore shaped Shorten’s reputation too.

Perhaps he enjoyed exercising power too much to realise, or care.