AARON PATRICK: The bill for investigating 19 Afghan war veterans is about to hit $17 million each

AARON PATRICK: By the end of 2025, the Government will have spent an eye-watering amount investigating 19 veterans, mostly from the SAS. The time may have come for a national debate on military prosecutions.

When it comes to investigating Australian soldiers accused of misconduct in the Afghanistan war, justice is proving to be very slow and expensive.

The government has allocated $318 million over a decade to the investigations, including this financial year. This equates to $17 million each for the 19 soldiers who a NSW judge, Peter Brereton, recommended in 2020 face prosecution.

Despite the generous budget and a staff of around 160, the Office of the Special Investigator created to turn Justice Brereton’s findings into court-level evidence has charged only one person in four years: Oliver Schulz, a former Special Air Service soldier accused of executing a detainee in a field in 2012. His trial is unlikely before 2027.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.The other 18 veterans do not know when or if AFP officers will one day arrive with handcuffs. They are no longer the young, thrill-seeking men who fought in the brutal war against the Taliban. In some cases, their alleged crimes date back 20 years. Most are middle-aged, leading quiet lives in Australia and overseas.

The special investigator, ex-judge Mark Weinberg, is barely accountable to Parliament, let alone the public. Unlike senior public servants, he does not take questions from the parliamentary committee that oversees his agency. He does not give interviews. His office refuses to provide any public indication of when or how many soldiers it intends to seek charges against.

A nation divided

No surveys have been published about Australians’ views on prosecutions of veterans, but it is not hard to work out that we’re hopelessly split.

Influential leaders in politics, the military, the law and media want to see what they regard as justice carried out. They understand the law has to apply even in the extremes of war, not just to protect civilians’ and prisoners’ lives, but soldiers from the moral harm caused by unjustified killing.

Many are ambivalent. Others are disgusted by the pursuit of men — they would say hounding — who fought a dirty war. Taliban fighters did not wear uniforms and had no laws of war to follow. Among their crimes were the execution of public servants delivering essential services to regular Afghans, who the Taliban worried would bolster support for Afghanistan’s elected government.

The day before the start of the Battle of Shah Wali Kot — the fight for which Ben Roberts-Smith would be awarded a Victoria Cross — the Taliban hung a seven-year-old boy from a tree for passing on information about their movements, he New York Times reported.

Special forces

Western forces responded to the Taliban’s tactics with a legal assassination program.

The Special Air Service Regiment was an enthusiastic participant. The small teams the regiment is organised around were each given a list of six or so Taliban commanders. It was their job to hunt them down and kill or capture them. They often didn’t care which, given captured Taliban leaders often used time to government prisons to recruit for the insurgency.

The SAS and their fellow special forces unit, 2nd Commando Regiment, were good at their job. Their job was killing.

Of the 41 soldiers who died in Afghanistan, almost half were from these units, a statistic that points to their willingness to fight.

The West lost the war not because of a lack of weapons or soldiers, or a failed strategy. Australian forces had pacified most of their area of responsibility in southern Afghanistan by the middle of 2010, when they entered into districts barely touched by Western forces since the initial invasion in 2001.

The Taliban were victorious because it possessed a greater willingness to kill, and be killed, than the West. Credible estimates put their losses over the 20-year war around 85,000.

The Afghan syndrome

The first misconduct allegations against Australian soldiers date back to as early as 2009. Over the years they received so much coverage that they came to overshadow the entire war, which most Australians never really understood.

Today, the association between Afghanistan and war crimes is so strong that many veterans are reluctant to talk about their service. The war is shrouded in a collective shame that makes it difficult, if not impossible, for individual and collective acts of heroism to be celebrated. Outside their own small community, Afghan combat veterans face the cold glare of public opprobrium.

Perhaps the best example is the Battle of Shah Wali Kot, Australia’s greatest modern military victory.

One of the commandos who found himself pinned down by an ambush during the battle, Dean Parkinson, was asked by his young son after he returned: “Did you murder anyone over there, Dad?”

The Afghan syndrome may be worse than the treatment of Vietnam veterans in the 1970s. Although they returned from a failed, unpopular war, Vietnam vets were not accused of individual crimes. Eventually, they were celebrated in movies, books and monuments.

Australian forces made mistakes in Afghanistan. That did not make it an unjust war. Under Taliban rule, a flourishing liberal society has been snuffed out by an austere Islamic theocracy. Press freedom has ended. Women are not allowed to attend high school. Political opponents are arrested and tortured. Public executions have resumed.

The time may have come for a national discussion about the prosecution of war veterans. There are passionate arguments on both sides. These men fought in our names. As a society, we are collectively responsible for their actions.

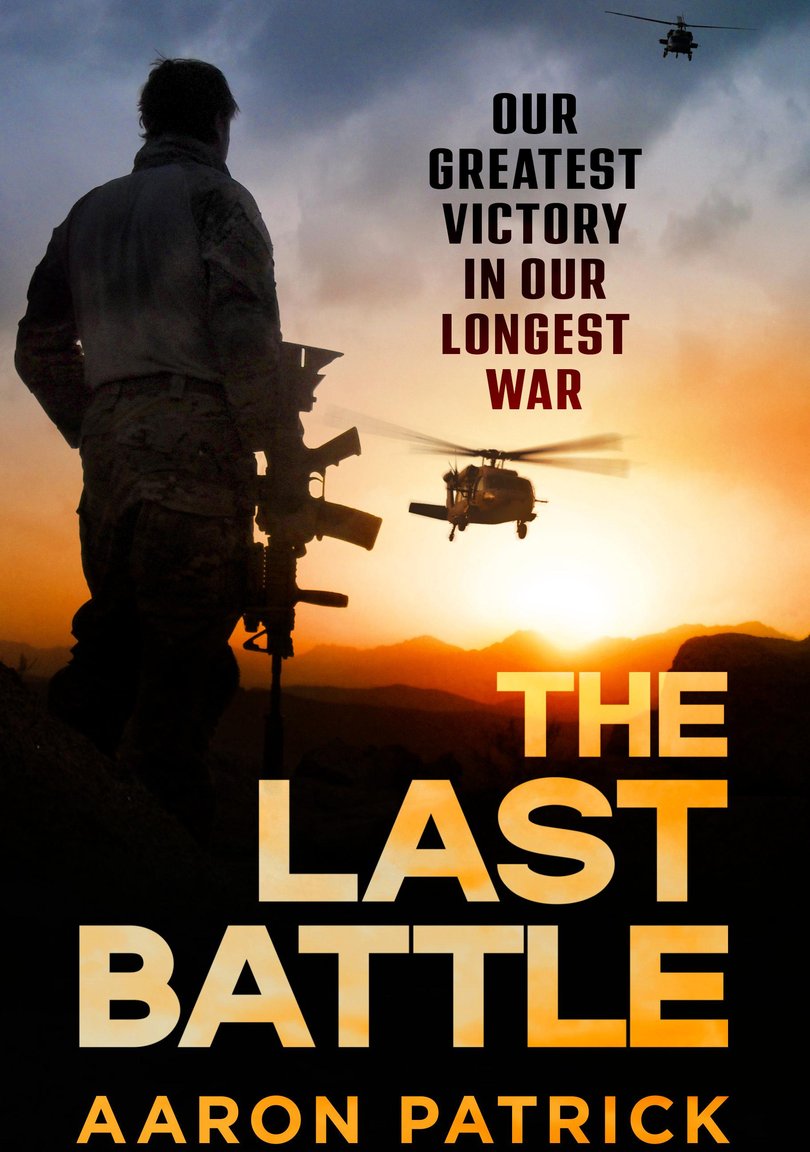

Aaron Patrick’s book on the Battle of Shah Wali Kot, The Last Battle, goes on sale Tuesday.