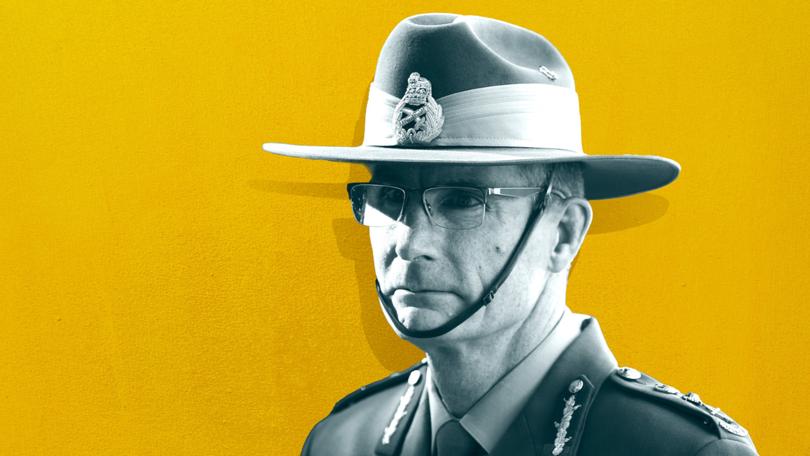

Angus Campbell officially hands over the Australian Defence Force to successor David Johnston

Angus Campbell has officially stepped down as chief of the Defence Force after six years, leaving the military in what veterans and Diggers have described as its ‘worst state ever’.

Angus Campbell has officially stepped down as chief of the Defence Force after six years, leaving the military in what veterans and Diggers have described as its “worst state ever”.

At a changing of the guard ceremony on Wednesday, Admiral David Johnston assumed the position after six years as vice-chief, becoming the first naval officer to helm the military since 2002.

Regarded by the government as a “safe pair of hands”, he will be under pressure to address crippling internal morale issues, problems with leadership and structure, and a retention and recruitment crisis that, all up, has made some personnel reluctant to let their children join the military.

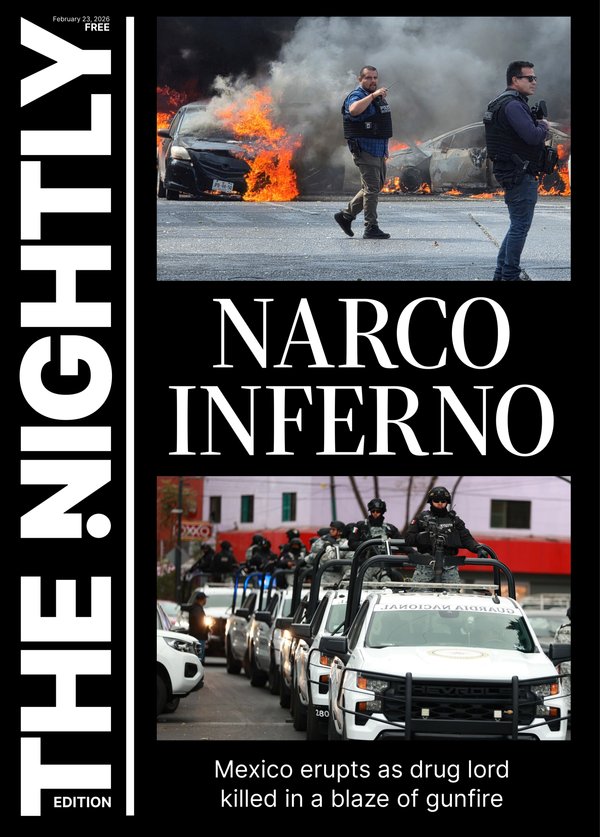

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.General Campbell’s tenure ended as his own Distinguished Service Cross came under scrutiny, with the senate last week agreeing to put the military’s honours and awards system under the microscope.

The move came after The Nightly reported dozens of retired and serving personnel put to Defence Minister Marles that the system was being “abused” and the now-former chief’s medal was without merit.

His successor hailed General Campbell for demonstrating a “determined focus on building a better ADF that is trusted to defend, respectful of its people, and more capable in operations”.

But the sentiment among the defence community suggests deep unhappiness with the state of the force under General Campbell’s leadership.

Describing his tenure as an “extraordinary privilege”, General Campbell in his final address acknowledged the ADF was “deeply flawed and imperfect”, but would be improved under the new-look leadership team spearheaded by Admiral Johnston.

“We are prepared to see ourselves, to learn, and to improve. Indeed, if nothing else, I would claim the ADF is a truly learning organisation,” he said.

“Our journey is the product of many striving together. Today’s ADF is a far better and more capable force than the one I joined so many years ago.

“As for any departing chief, I leave knowing there is much more to do. But that is now for others.”

At a time of increasing strategic competition in the Indo-Pacific requiring the strongest possible military, retired Australian Special Forces Commando Wes Hennessy CSM said General Campbell had left the force in an atrocious state.

“You’ve got a massive retention crisis, a massive recruitment crisis, serious morale issues and several capability shortfalls,” he said.

“There’s no national strategic defence strategy and no unified strategy. That directly impacts our national security.”

Michael Shoebridge, director of Strategic Analysis Australia, said it was unlikely Admiral Johnston could effectively turn things around because he was not the “driven, practical decision maker” the force needed in the current climate.

“We need a practical person with a strong individual drive and a far more practical understanding of what current warfare is and what it requires,” he said.

At home, one of the most significant issues Admiral Johnston will need to address is the major personnel shortfall, with the force seven per cent below its authorised strength of 62,735. The federal government has also set an ambitious goal of boosting its workforce by 18,500 people by 2040 — a 30 per cent increase on current levels.

In a bid to bolster numbers, New Zealand permanent residents who meet requirements are now allowed to sign up for the defence force, with citizens from the United States, United Kingdom and Canada able to join from January.

Admiral Johnston on Wednesday said while progress was being made to boost the numbers, defence had a way to go.

“This will require us to broadly examine our employment models, and how best we use our highly capable part-time and reserve force,” he said.

But, those efforts are complicated by a more competitive job market that makes it more difficult to attract new talent, as well as what some in the defence community say is a “damaged reputation”.

Then, there is the problem of retaining the existing force, with the military conceding ongoing work is needed to prioritise wellbeing and fostering a more productive workplace to improve low morale.

Mr Shoebridge said the defence force had no one to blame for the problem but itself.

“Why would anyone join or stay in the military where they have no responsibility, they’re not trusted to take any decisions until they become old and senior, and when the systems in the military are starting to look like an aged care home — like the Collins submarines and Anzac frigates,” he said.

Some say the morale problem stems from issues among defence leadership, with Defence Minister Richard Marles earlier this year conceding “issues of culture within the higher echelons of the Defence force and the department” were having an impact on the force.

Mr Marles has pointed to a rotating door of defence ministers under the previous Coalition government and their tendency to announce undeliverable defence projects as a significant contributor to low satisfaction.

But defence members say there is a problem more broadly with a growing disconnect between the force’s leadership and the soldiers, sailors and aviators.

There is a hope that Admiral Johnston can “affect change”, but some have warned nothing will be different unless the defence force moves away from its business-as-usual approach.

Mr Hennessy said Admiral Johnston needed to prioritise talking to junior leadership and soldiers, cut down on the burgeoning number of officers, and focus on building out the infantry force which had a “catastrophic” shortfall in sergeants.

“We have got a real shortfall in our main fighting element… And the more general officers we have and the less juniors — as a military, we are less combat effective,” he said.

“The new CDF should be very much down and in… and get some feel of what’s happening on the ground.

“He has an extraordinary amount of detailed work in front of him to rebuild a modern, enabled and capable ADF.”

Some members of the community are also concerned that the training structure, including for rising officers, lacks lived experience that could put lives at risk.

One serving defence member, a fourth generation service person who asked not to be named out of fear of repercussions for speaking out, said they were worried if their children joined their lives “will be spent needlessly by a low-ability officer”.

“If you’re under poor command, that costs people’s lives. This is the highest stakes game there is,” they said.

Mr Shoebridge said if rising young officers were equipped with modern technology and trusted to make decisions, it would strengthen the force.

“Until defence start bringing obvious leading tech and weapons into the force... young people won’t think they’ll be as equipped for war, so why would they join,” he said.

“There’s also the problem of lack of trust of junior officers, who are intelligent and highly trained, but aren’t trusted to make coffee. When their experience and skill is valued far more outside of the military, why would they stay.”

Another major issue plaguing the defence force has, for many years, been mental wellbeing, and suicidality.

Over three years, the Royal Commission into Veteran and Defence Suicide laid bare what the commission heard was a “catastrophic failure” in senior government and Defence leadership that led to a “senseless loss of life” in Australia’s military community.

When he appeared, General Campbell apologised unreservedly for “deficiencies” in supporting veterans, and acknowledged shortfall in “wellbeing support and care” that led to 1600 suicides between 1997 and 2020.

The final report, due by September 9, is set to advise the government and defence force on urgent reforms needed to deliver improved health and wellbeing outcomes for personnel and veterans.

Admiral Johnston on Wednesday said he would work to understand the commission’s judgments, and “work at pace to implement the government’s agreed recommendations”.

“Along with the senior leadership team at the department, I am fully committed to prioritising programs that foster a culture that prioritises wellbeing so our people can serve well, live well, and age well,” he said in his inaugural address.

Admiral Johnston must address all of these internal issues while also pushing defence into a greater sense of urgency about responding to rapidly changing strategic outlook, with this year’s defence strategic review revealing Australia “no longer has the luxury of a ten-year window of strategic warning time for conflict”.

“My role is to ensure that the ADF is ready now and into the future able to protect our nation’s security,” he said on Wednesday.

“This requires a force that is well equipped, trained, confident, strong and resilient.”