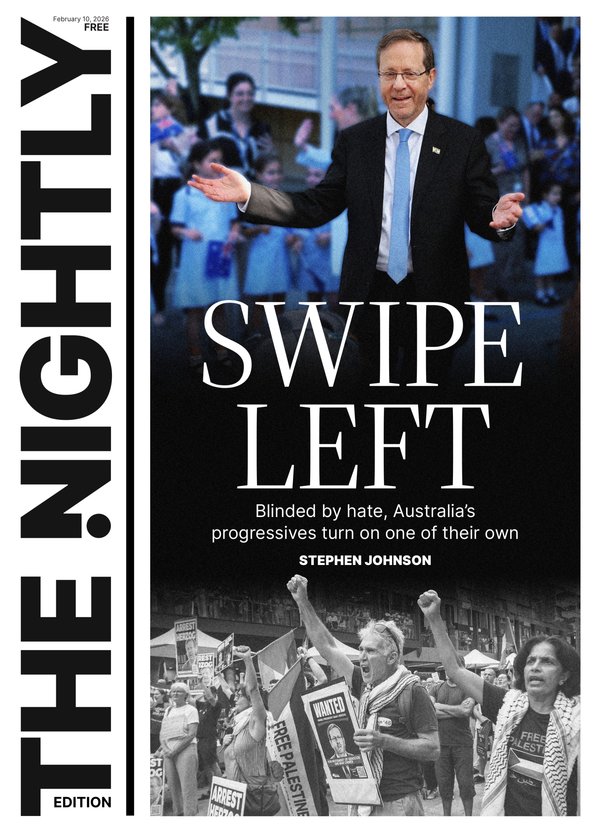

AARON PATRICK: Afghanistan war crime probe pressure building to resolve investigation into SAS

AARON PATRICK: An unusual alliance of the Liberal and Greens parties is pushing for a quicker resolution to investigations that have cost $17 million per veteran and secured no convictions.

Leaders on the left and right of politics are becoming exasperated with long-running, expensive and controversial war crimes investigations into Afghan War veterans.

The Coalition’s defence spokesman, Angus Taylor, told The Nightly the $318 million allocated to pursuing former soldiers raises “raises real questions about efficiency, proportionality and basic fairness” given that only person has been charged and no one convicted.

Now middled aged, the veterans are “raising families, contributing to their communities, yet they continue to live under a cloud of suspicion for events two decades old,” Mr Taylor said, yet they face criminal prosecutions that could run into the 2030s.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.“That’s unacceptable,” he said. “Justice delayed for decades is justice denied.”

Opened five years ago, the Office of the Special Investigator is responsible for building cases against the 19 men, most of whom were members of the Perth-based Special Air Service Regiment.

With Afghanistan under Taliban control, investigators have admitted that they have given up trying to get evidence from Afghan civilians. This forces the Government to rely on documentary evidence, including video recordings, and testimony from other soldiers.

Three F-35s

Very little information has emerged about the progress of the investigations, but lawyers following the situation fear the large amount spent so far — $17 million per veteran — is creating a momentum towards prosecutions that may be hard to stop.

The one defendant, former SAS trooper Oliver Schulz, won’t be tried before 2027.

Unless he can convince the Commonwealth Director of Prosecutions to charge more veterans, the lawyer at the Office of the Special Investigator in charge of the investigations, Mark Weinberg KC, will likely be criticised for spending the equivalent of three F-35 jet fighters fruitlessly pursuing Australian soldiers.

“The way it has dragged on for almost a decade risks becoming a denial of justice in itself,” Mr Taylor said. “If there is sufficient evidence to prosecute, that should happen without delay. If not, these cases should be closed.”

Critics of the investigator’s work aren’t only conservatives. A Greens senator from NSW, David Shoebridge, has complained for years about the progress of the probe and the investigator’s refusal to answer basic questions.

“There needs to be accountability in this office to explain the delay and explain what on earth has happened for such a vast sum of public money,” Senator Shoebridge told The Nightly on Wednesday.

Asked about the criticism, the Office of the Special Investigator made a rare concession to the veterans it is pursuing. “The OSI is conducting our work as expeditiously as possible and acknowledges the potential impact of our work on the welfare of those involved,” a spokeswoman said.

A dirty war

Within the small community of ex-special forces soldiers, the war remains painful. Many feel the war crimes allegations overshadow their service, making it difficult or impossible to celebrate their bravery and military successes.

Some are critical of the SAS. Some veterans believe the SAS had an arrogant culture that got out of control without adequate supervision from officers, leading to unnecessary Afghan deaths that morally compromised soldiers and damaged the army’s reputation.

Others say the SAS was simply reacting to the enemy’s tactics. The day before the Battle of Shah Wali Kot, for example, the Taliban hung a seven-year-old boy accused of passing on information to the Americans from a tree in a village, the New York Times reported at the time.

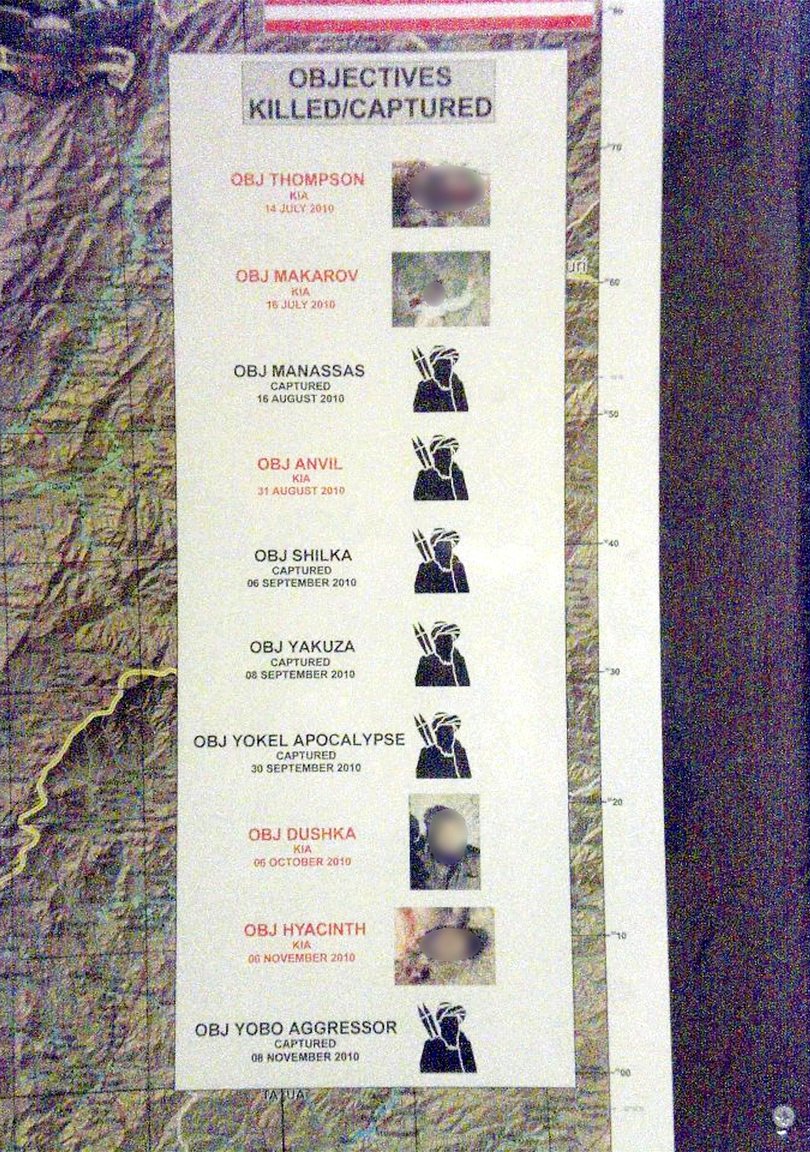

In response to Taliban tactics, Western forces maintained a list of Taliban commanders who could be killed at any time. The talib commanders were assigned to SAS teams led by sergeants, whose job it was to track them across southern Afghanistan and kill or capture them.

In a dirty war, the SAS seemed indifferent to the outcome. Dead Taliban leaders were no longer a threat. Captured talibs were turned over to the Afghan government, which put them in prisons where they often continued to organise the resistance.

Knowing this, Afghan soldiers who went on missions with Australia’s special forces sometimes had to be restrained from executing suspected Taliban prisoners, former soldiers told The Nightly.

‘More than talk’

Influential forces in politics, the law and the media support prosecutions. Two weeks ago academics from Perth’s Murdoch University argued Mr Schulz’s prosecution would be “an opportunity” for Australia “to make an important contribution to the field of international criminal law”.

That’s because courts have not conclusively determined when civilians’ deaths in war are justifiable, a gap historians Paul Taucher and Rhys Knapton-Lonsdale said Mr Schulz’s prosecution could fill.

“By clearly showing that Australian soldiers like Schulz are not immune to prosecution, the Government can demonstrate Australia’s long and vaunted commitment to international law is more than just talk,” they wrote on The Conversation website.

The Office of the Special Investigator has claimed credit for the first civilian murder prosecution of a soldier for actions on the battlefield. But Mr Schulz, who has pleaded not guilty, is not the first Australian soldier to be tried for murder.

In 1901 Queensland lieutenant Henry Morant was charged with executing prisoners while leading the Bushveldt Carbineers, a special forces unit fighting an insurgency in South Africa. Also known as Breaker Morant, he was found guilty and executed by a British firing squad on February 27, 1902.

While Morant was likely guilty, his death sentence “resulted from political pressure”, according to the Australian War Memorial, a sentence that suggests that the prosecution of prominent soldiers has long been caught up in politics.